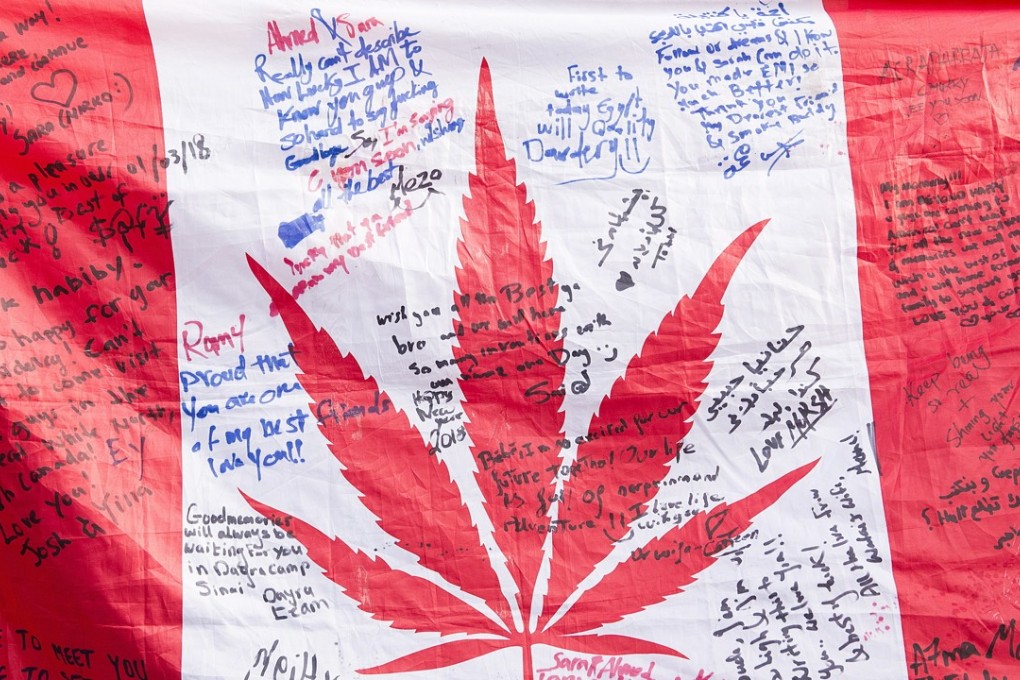

Ganja gap: after marijuana legalisation, Asian-Canadians tread a cultural divide over getting high

- Marijuana is now legal in Canada

- But Asian communities are grappling with a generational gulf when it comes to attitudes about the drug

When Hongkonger Andrea Tam first moved to Canada at the age of 16 in the early 90s, she was struck by the sheer size of the world’s second-largest nation – home to less than 37 million people and roughly 3,600 times the size of Hong Kong.

Tam also found herself in awe of the sense of boundless freedom that accompanied the spaciousness.

“You would go to your high school and just walk outside; there were no school gates like in Hong Kong, no [guard] at the door,” she said. “You could leave anytime.”

It was just outside her Vancouver school, on the pavement known as the “smoke pit”, where Tam got her first taste of Canada’s marijuana culture.

“Walking by, I knew if someone had smoked it and I learned what it smelled like,” she said. “That was my first knowledge of marijuana.”

Tam, now a 39-year-old advertising executive in Vancouver who occasionally uses marijuana, says these encounters greatly altered her perception of the drug, which became legal in Canada on October 17.