Advertisement

China set to surpass US as Australia’s main academic collaborator, report finds

- The newly uncovered trend has raised national security concerns and led to calls for greater due diligence in partnering with Chinese institutes

- Others, however, dismiss such talk and say limiting engagement with the rising power is unlikely to improve its human rights record

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

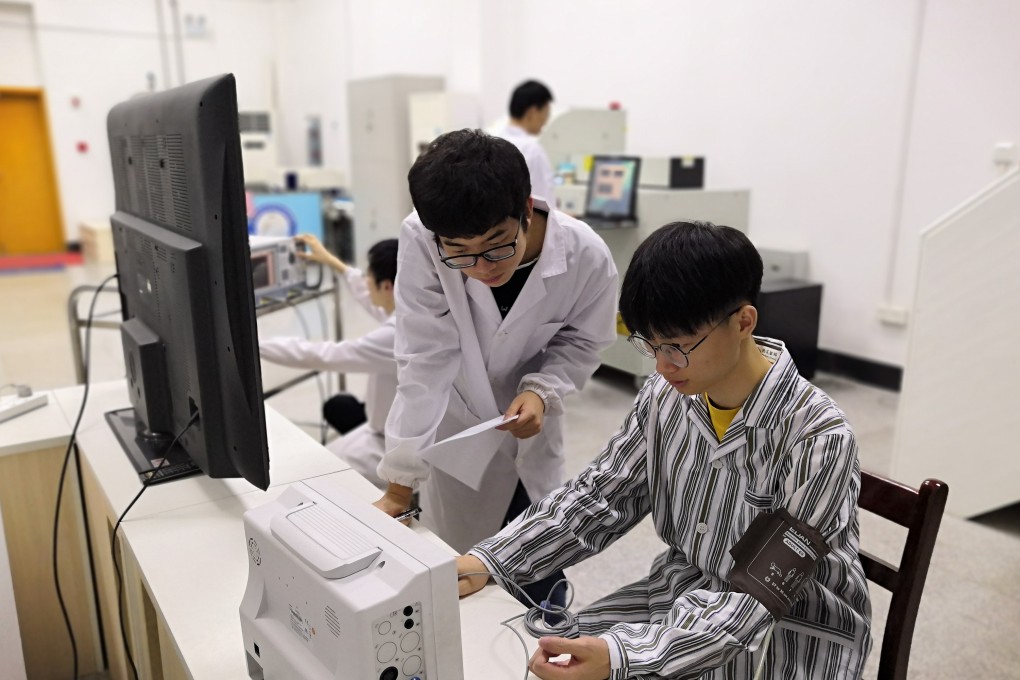

China will overtake the United States as Australia’s main collaborator on scientific research within months, a new report has found, spotlighting the continued debate in academia between capitalising on funding for research and protecting national security and human rights.

The Sydney-based Australian-China Relations Institute (ACRI) found that the switch could take place as early as the end of this year, based on the number of Australian peer-reviewed papers with a China-affiliated co-author.

Advertisement

Only 1 per cent of said papers had a co-author from a Chinese institution in 1998, jumping to 15 per cent last year. Those with an American co-author, meanwhile, increased from 11 to 16 per cent over the same period, according to the report released on Friday.

The number of papers jointly written by Australian and Chinese academics among the most-cited top 1 per cent has also increased – from just four in 1998 to 389 in 2017, the report added.

This newly uncovered trend has led several academics to call for greater due diligence in partnering with Chinese institutes, while others said limiting engagement with the rising power would not improve its human rights record. China has come under fire recently for the mass detention of Muslims and other minorities – most notably Uygurs – in its westernmost province of Xinjiang, though Beijing maintains this is necessary for national security reasons.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x