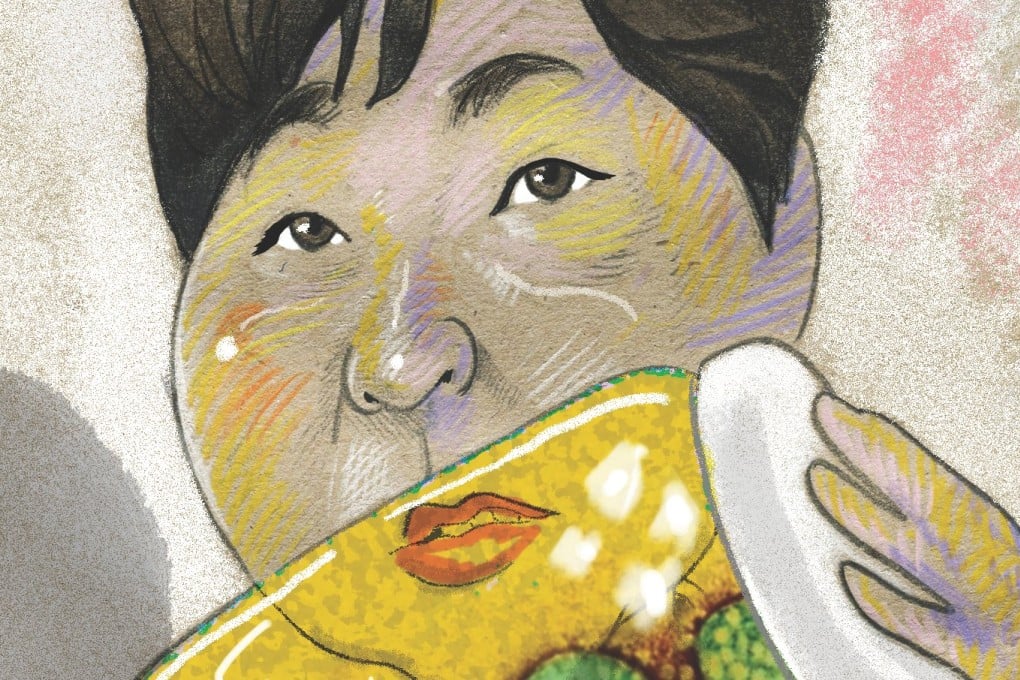

Park Geun-hye under fire over handling of Mers crisis

The South Korean president has been criticised for her slow response to the deadly outbreak, one year after facing flak over the ferry tragedy

President Park Geun-hye is finding herself at the helm of her second national crisis as Mers hysteria sweeps South Korea, but it is not yet clear if her grip has got any firmer.

The nation's first female leader and her administration faced an avalanche of public and media criticism in April last year for what was widely perceived as a failed rescue operation and a botched recovery effort when the Sewol ferry sunk, dragging more than 300 people, largely schoolchildren, to graves in the Yellow Sea.

Now, with the nation reeling from a Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak that has killed 14, infected nearly 140 and forced 3,680 into quarantine, the government-bashing is scarcely less ferocious.

"Stricken with incompetence, this administration is beyond recovery," the leftist Hankyoreh newspaper said in an op-ed. But while the Hankyoreh can always be relied upon to slam the conservative Park, the left-wing flagship has not been alone in its criticism.

Economy-focused titles have joined the critical barrage, with the Aju Business Daily opining that "the government has caused a catastrophe due to the absence of a proper reaction". Most damningly, the country's most popular, most influential newspaper - the right-wing Chosun Ilbo, usually a natural ally of Park - asked: "Where is the leadership in this Mers crisis?"

The question was germane. Park is the only daughter of Park Chung-hee, the strongman general who seized power in a 1961 coup and oversaw South Korea's "zero-to-hero" economic success story. Park, who won the presidency in 2012, has been named the 11th most powerful woman in the world by Forbes magazine.