Japan cult spin-offs persist two decades after subway sarin attack

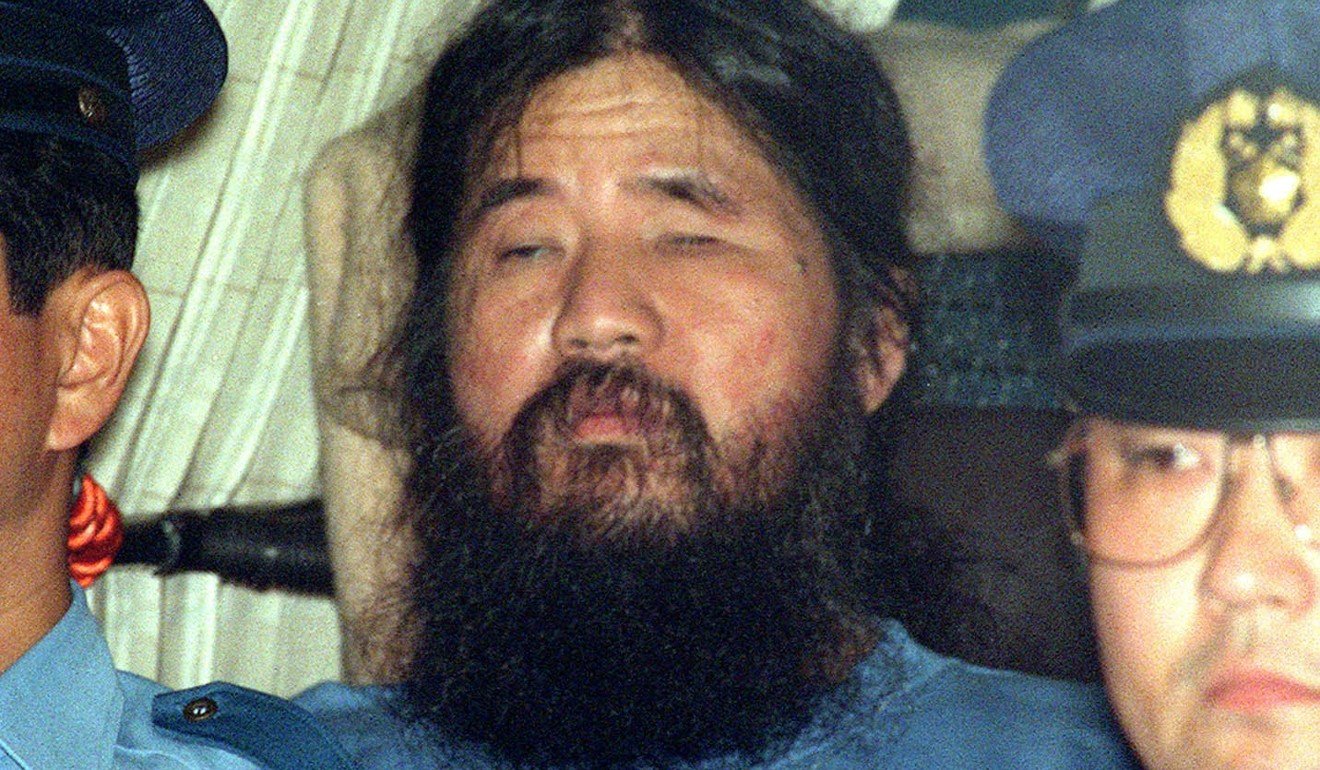

Followers of Shoko Asahara’s Aum Shinrikyo split up after deadly 1995 nerve gas attack and severed ties, but there are fears execution of its leaders may renew interest in the doomsday cult

More than two decades after Japan’s Aum Shinrikyo cult plunged Tokyo into terror by releasing a nerve agent on rush-hour subway trains, its spin-offs continue to attract new followers.

Cult head Shoko Asahara is on death row, along with 12 of his disciples, for crimes including the subway attack, which killed 13 people and injured thousands.

He was arrested in 1995 in the wake of the sarin attack, but the Aum cult survived the crackdown, renaming itself Aleph and drawing new recruits into its fold.

Aleph officially renounced ties to Asahara in 2000, but the doomsday guru retains significant influence, according to Japan’s Public Security Intelligence Agency.

“[Aleph] is a group that firmly instructs its followers to see Asahara as the supreme being,” an agency investigator said, speaking on condition of anonymity. “If someone says ‘guru Asahara wants to bring down Japan’, there would be followers who would act. The group poses such a potential danger.”

Raids on Aleph facilities have found recordings of his teachings as well as a device used by the Aum cult known as a “Perfect Salvation Initiation”, a type of headgear that emits weak electric currents which members believe connects them to Asahara’s brainwaves.

Aleph and other splinter groups, which deny links to Asahara despite the claims of authorities, have 1,650 members in Japan and hundreds more in Russia, according to the Public Security Intelligence Agency.

It says the groups attract around 100 new followers annually via yoga classes, fortunetelling and other activities that do not mention the cult’s name, often targeting young people who do not remember the 1995 subway attack.

“Young female followers go to ‘training’ places with their children … We are worried there is an increasing number of children who have been inculcated by the Aum since they were very young,” the investigator said.

Asahara and his wife Tomoko had four daughters and two sons, and most of the family is still in the cult.

One daughter who left in 2006, aged 16, has described horrifying ordeals during her childhood, including being forced to eat food with ceramic shards in it and being left in the cold in little clothing.

“It was an environment unthinkable in modern-day Japan. I was afraid I would be killed if I rebelled, so I felt tense, as if I were on a battleground, for 16 years,” she said last year. “I strongly hope no more children will grow up in the Aum’s successor groups.”

In early March, on Asahara’s 63rd birthday, investigators were keeping their usual close eye on the headquarters of an Aum splinter group in a quiet Tokyo residential area.

“We are not marking the day in any way,” said Akitoshi Hirosue, deputy head of the Hikarinowa (The Circle of Rainbow Light) group.

“We actually think Asahara should be executed,” he said at the group’s headquarters.

Hikarinowa split from Aleph in 2007 under the leadership of flamboyant former Aum spokesman Fumihiro Joyu, and now has around 100-150 members.

“As long as the death penalty is not implemented against him, Asahara is the ‘saviour exempt from execution’ and helps Aleph win more followers,” Joyu recently said in arguing for the death of his former guru.

Aleph training halls are closed to media and the group did not respond to enquiries by AFP.

Taro Takimoto, a lawyer who has helped relatives of cultists for decades, supports capital punishment for Asahara but not the 12 other members on death row, who he says only acted as “limbs” of the guru.

He fears the 12 members will “become martyrs” if executed, only boosting cult recruitment.

Seven of those on death row were moved to different prison facilities in recent days, prompting speculation that they could soon be executed. It was not clear whether Asahara was among them.

“We should have them talk until they die a natural death so that they help prevent a recurrence,” Takimoto said.

And he said they deserve some understanding, describing them as “good people” who were brainwashed by Asahara.

“Asahara was more than God to them, the person who knew the entire universe and all its reincarnations. Orders from Asahara were orders from the universe,” he said.

Asahara’s execution may draw a line under the Aum’s crimes for some Japanese, but Takimoto warns it could also trigger suicides among his followers and lead to the appointment of a successor guru.

A leading candidate is Asahara’s second son, according to Takimoto.

“If the second son, bearing Asahara’s ashes, declares himself ‘guru’, he would gain serious religious authority,” opening a new chapter on the cult, Takimoto said.

.png?itok=arIb17P0)