How Pakistan’s ‘communication war’ is silencing critics and journalists – but failing to shut down banned organisations

Dozens of groups with terrorist links or accused of being purveyors of sectarian hate are flourishing on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram

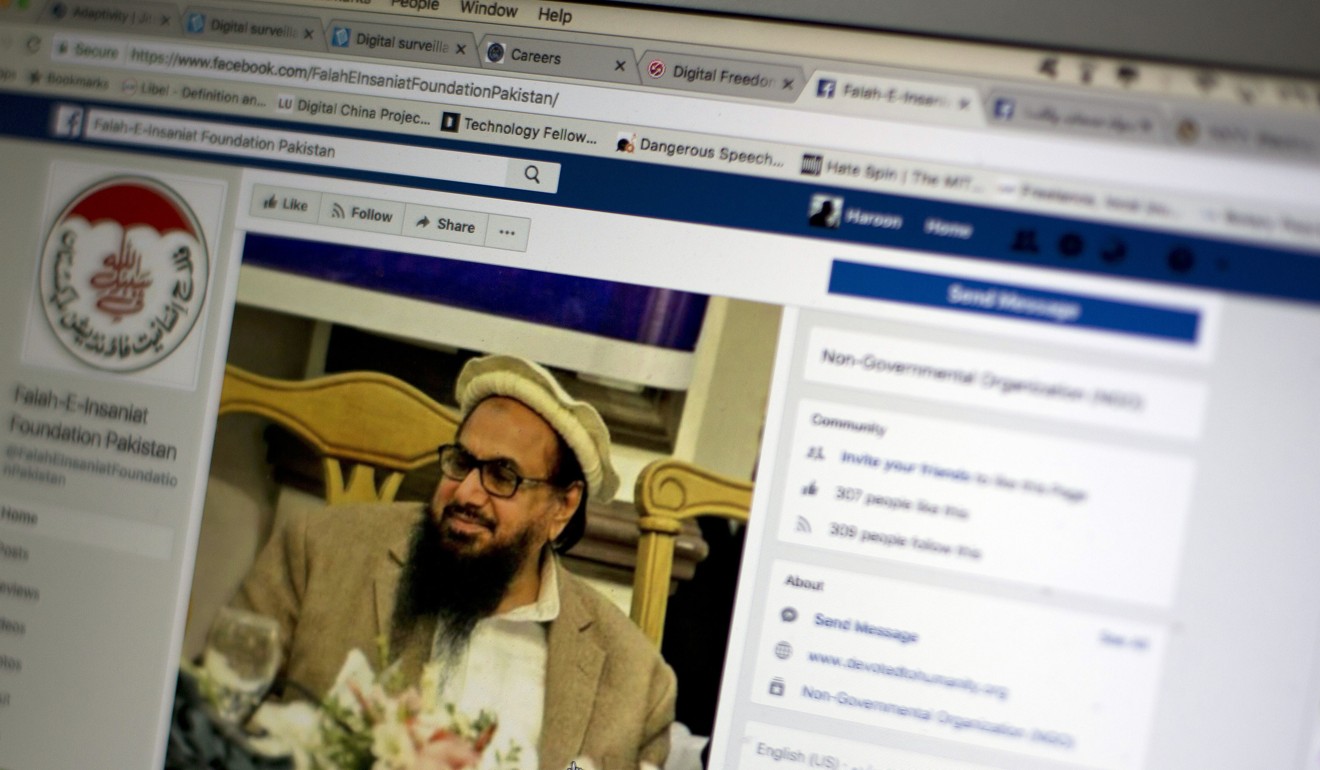

The shadows of three men brandishing assault rifles welcome the reader to the Facebook page of Lashkar-e-Islam, one of 65 organisations that are banned in Pakistan, either because of terrorist links or for being purveyors of sectarian hate.

Still more than 40 of these groups operate and flourish on social media sites, communicating on Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Telegram, according to a senior official with Pakistan’s Federal Investigation Agency (FIA) who is tasked with shutting down the sites. They use them to recruit, raise money and demand a rigid Islamic system. It is also where they incite the Sunni faithful against the country’s minority Shiites and extol jihad, or holy war, in India-ruled Kashmir and in Afghanistan.

“It’s like a party of the banned groups online. They are all on social media,” the FIA official said.

Meanwhile, Pakistan is waging a cyber crackdown on activists and journalists who use social media to criticise the government, the military or intelligence agencies. The Interior Ministry even ordered the FIA – Pakistan’s equivalent of the American FBI – to move against “those ridiculing the Pakistan Army on social media”.

The FIA official said the agency had interrogated more than 70 activists for postings considered critical. All but two have been released, with a third still under investigation, he added.

Activists, journalists and rights groups who monitor Pakistan’s cyberspace have said the banned groups active on social media operate unencumbered because several are patronised by the military, its intelligence agencies, radical religious groups and politicians looking for votes.

Even the FIA official has conceded state support for some of the banned groups, but said it is a global phenomenon engaged in by all intelligence agencies.

“Everyone is protecting their own terrorists. Your good guy is my bad guy and vice versa,” he said, adding that some sites belonging to banned groups are intentionally ignored to gain intelligence.

Facebook and Twitter have said they ban “terrorist content”. In the second half of last year, Twitter said it had suspended 376,890 accounts on its site because they were thought to promote terrorism. However, the company said less than 2 per cent of them were the result of government requests. Facebook, meanwhile, said in a blog last month it uses artificial intelligence and human reviewers to find and remove “terrorist content”.

“There is no place on Facebook for terrorism,” Facebook spokeswoman Clare Wareing said. “Our Community Standards do not allow groups or people that engage in terrorist activity, or posts that express support for terrorism.”

Shahzad Ahmed, of the Islamabad-based social media rights group BytesForAll, said Pakistan’s military and intelligence agencies are waging a “communication war” against progressive, moderate voices and those who criticise the government and more particularly the military and its agencies. They use radical religious groups to promote their narrative, he said.

“Their connectivity on the ground, the mosques, madrassas and supporters translates into social media strength and they are (further) strengthened because they feel ‘no one is going to touch us’,” he said.

Ahmed Waqass Goraya is a blogger who was picked up and tortured by men he believes belonged to the country’s powerful intelligence agency, known by its acronym ISI. He said Pakistan’s social media space is dominated by armies of trolls unleashed by the military, intelligence agencies and allied radical religious groups to push their narrative. That narrative includes promoting anti-India sentiment – India is Pakistan’s long-time enemy against whom it has fought against in three separate wars.

Critics who openly accuse the military of using extremists as proxies are under attack, said Goraya. He fled Pakistan after social media was used to suggest he and other bloggers were involved in blasphemy, a charge that carries the death penalty. Even the suggestion in Pakistan that someone insulted Islam or its prophet can incite mobs to violence.

Earlier this month, Taimoor Raza, a minority Shiite and Pakistan-based journalist with France 24 and an active social media, became the first person sentenced to death under Pakistan’s blasphemy law for a social media posting.

At FIA headquarters in the capital, Islamabad, the official said banned groups use proxy servers that reveal IP addresses buried somewhere in other countries, making it impossible to track.

That explanation was called “lame” by Haroon Baloch, a social media rights activist who has studied the banned groups’ use of social media. He said sites can be blocked, users located and the persons running the pages stopped.

But unlike the banned groups, Baloch said bloggers, social media activists and journalists are found and stopped because Pakistan’s civilian and military intelligence agencies are out to get them.

“Agencies have established a new wing to monitor 24/7, to counter liberal and progressive debate and particularly anything that criticises their policies,” he said.