Deep sea grave robbers are stripping Asia’s rusted warship wrecks for ‘radiation-free’ steel

The unmarked graves of thousands of sailors are threatened by illegal metal salvagers

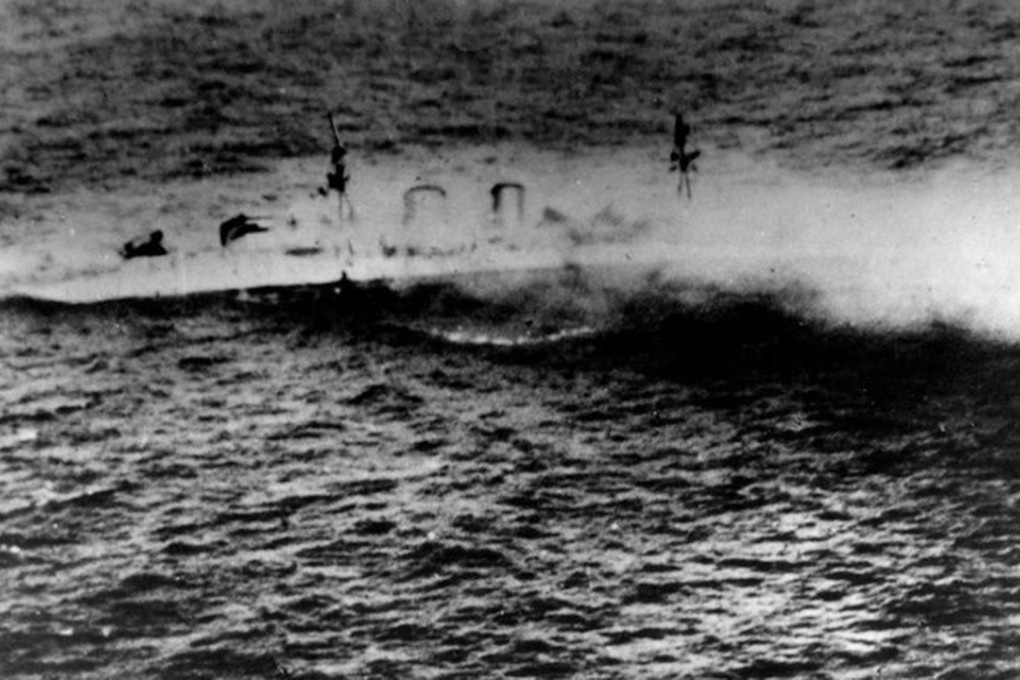

Dozens of warships believed to contain the remains of thousands of British, American, Australian, Dutch and Japanese servicemen from the second world war have been illegally ripped apart by salvage divers.

An analysis of ships discovered by wreck divers and naval historians has found that up to 40 second world war-era vessels have already been partially or completely destroyed. Their hulls might have contained the corpses of 4,500 crew.

Governments fear other unmarked graves are at risk of being desecrated. Hundreds more ships – mostly Japanese vessels that could contain the war graves of tens of thousands of crew killed during the war – remain on the seabed.

The rusted 70-year-old wrecks are usually sold as scrap but the ships also contain valuable metals such as copper cables and phosphor bronze propellers.

Experts said grave diggers might be looking for even more precious treasures – steel plating made before the nuclear testing era, which filled the atmosphere with radiation. These submerged ships are one of the last sources of “low background steel”, virtually radiation-free and vital for some scientific and medical equipment.

The Guardian revealed last year that the wrecks of some of Britain’s most celebrated warships had been illegally salvaged, leading to uproar among veterans and archaeologists, who accused the UK government of not moving fast enough to protect underwater graves.