Singaporean study links genetic diversity of tumours with resistance to treatment in Asian lung cancer patients

Researchers say lung tumours Asian patients are surprisingly more complex than initially thought

By Cynthia Choo

Researchers’ findings could pave the way for more precise and tailored treatments for lung cancer patients, as a new study in Singapore found that the genetic diversity of lung cancer tumours among Asian patients affects their response to treatment.

According to a study by scientists from A*STAR’s Genome Institute of Singapore (GIS) and medical oncologists from the National Cancer Centre Singapore (NCCS), lung cancer tumours in Asian patients contain much higher genetic diversity than previously expected.

“This results in a higher chance of them developing resistance to targeted cancer treatments such as drugs targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), a key driver gene of lung cancer,” said Dr Zhai Weiwei, a senior research scientist at GIS.

The two teams from GIS and NCCS studied 16 patients over a period of more than three years, with genetic information of tumours from about 35 more patients to be added in the continuation of the study.

About 80 per cent of those studied were Singaporean, and most were female, said Dr Tan Eng Huat, one of the authors of the study, and a senior consultant at the division of medical oncology at the NCCS.

Many of the study subjects were in their 50s and 60s, said the researchers. The youngest patient was 56-years-old, and the oldest was 77.

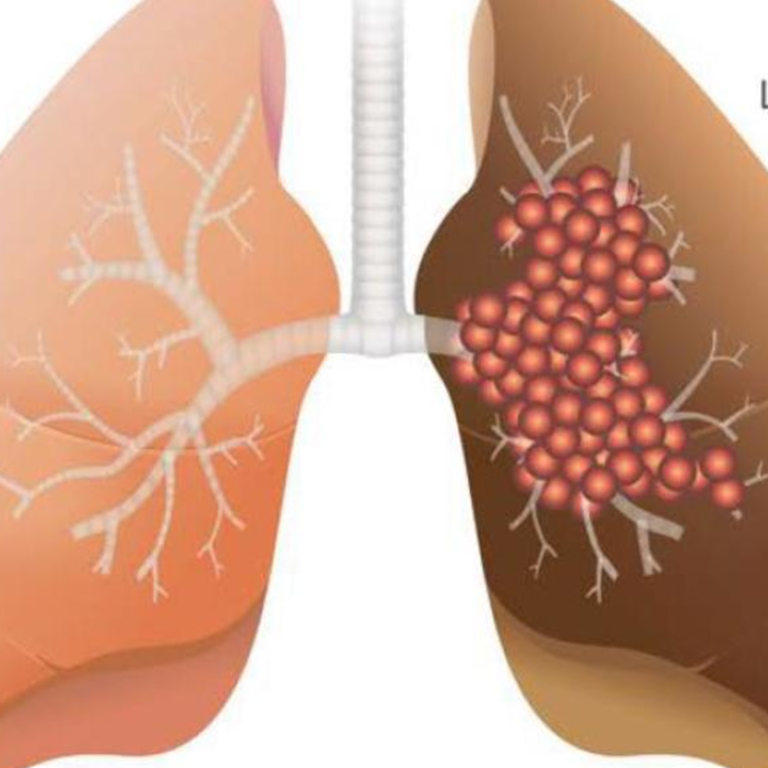

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related deaths among Singaporean men, and the second deadliest type of cancer among women here. This is based on data provided by the Singapore Cancer Registry from 2011 to 2015.

Dr Zhai pointed out that 85 per cent of all lung cancers in general are non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), and more than 50 per cent of the NSCLC patients were found to have mutations in the EGFR gene, a result that was significantly higher compared to the 15 per cent found in Caucasians.

While drugs targeting EGFR are effective in controlling the disease, the response is short-lived as most patients eventually succumb to cancer relapse in a matter of months or a few years. In some instances, patients do not respond to the drugs at all.

Dr Zhai said: “This is so as Asian patients have been observed to have higher tumour heterogeneity, that will lead to higher likelihood of developing a resistance to targeted treatments. Developing treatment strategies circumventing treatment resistance is very important for future work.”

“The study of the genetic complexity of tumours in Asian patients has provided us with new insights as to why they may quickly develop resistance after initial response to anti-EGFR drug inhibitors,” added Dr Axel Hillmer, principal investigator at GIS and co-corresponding author of the study.

Dr Tan said the standard treatments for EGFR gene mutations is the EGFR – Tyrosine Kinase inhibitor, during which three types of medicine are usually dispensed: gefitinib, erlotinib and afatinib.

With an understanding of the genetic complexities of lung cancer at diagnosis, doctors can potentially use a “more specialised and targeted cocktail of drugs that could potentially lengthen the survival of the patients, and decrease the chances of relapse,” added Dr Tan.

Dr Rahul Nahar, the first author of the study and a research associate at GIS, said the joint study is “one of the first major efforts to characterise and identify lung tumours in Singaporean patients on a large scale.”

He added: “It has generated a treasure trove of new genetic information and enabled us to perform detailed analyses, leading us to conclude that lung tumours in Asian patients are surprisingly more complex than previously appreciated.”