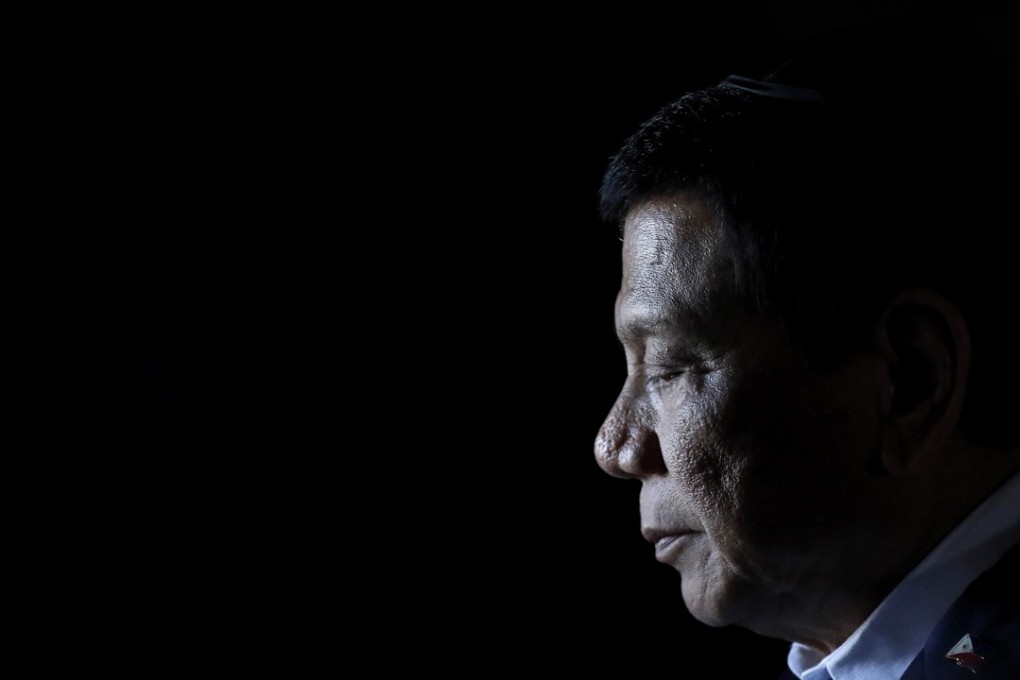

Philippines plans law to give Duterte Marcos-like powers

New legislation that would grant the Philippine president powers similar to martial law comes amid claims by critics that he made up the alleged ‘Red October’ coup plot to justify a crackdown on the opposition

The death penalty will be restored. Torture, allowed. Filipinos could be jailed for their posts on Facebook, Twitter and other social media. Suspected terrorists and even “unwilling witnesses” could be arrested without warrants and detained for 30 days without charge during an “actual or imminent terrorist attack”.

These are just some of the amendments proposed by Philippine security officials to the current Human Security Act of 2007 or Republic Act 9372.

The proposals come amid claims by the Duterte administration that the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines, the New People’s Army, together with opposition political parties and civil society groups, has been plotting a coup called “Red October” to overthrow the president.

However, the claims have been rubbished by critics, who say the plot has been made up to justify a crackdown on the opposition and pave the way for martial law.

In a Senate hearing on Monday, defence secretary Delfin Lorenzana pushed for approval of the new law, saying: “We won’t need to use martial law if we have something else that would give our security agencies a bit more teeth.”