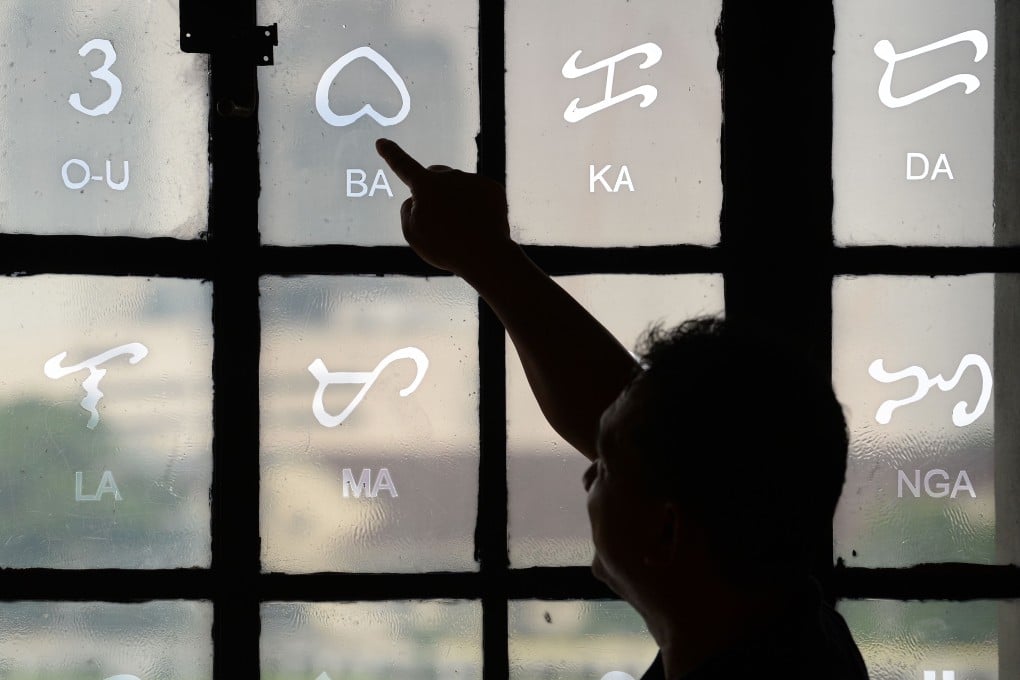

Why Philippine millennials are reviving Baybayin, an ancient written script

- Advocates for Baybayin, a 17-character indigenous script used before the Spanish colonisation, say it is a crucial part of Philippine identity

- But in a country with 131 government-recognised languages, critics say investing in the promotion of one ancient text over others is controversial and impractical

Online clips of calligraphy and digital fonts for Baybayin – a 17-character indigenous script last used hundreds of years ago – have gripped the digital generation and now it is appearing on everything from tattoos and T-shirts to mobile apps.

Proponents hail the curvilinear text as a crucial part of Philippine identity, but in a country with 131 government-recognised languages, critics say investing in the promotion of one ancient text over others is controversial and impractical.

“It’s bittersweet. It made me proud knowing our ancestors were literate,” said Filipino artist Taipan Lucero, 31, who studied calligraphy in Japan but returned home to apply his skills to reviving Baybayin.

“What’s sad about this is what’s being propagated in our education system. It’s like our history started with being colonised by Spain,” said Lucero.