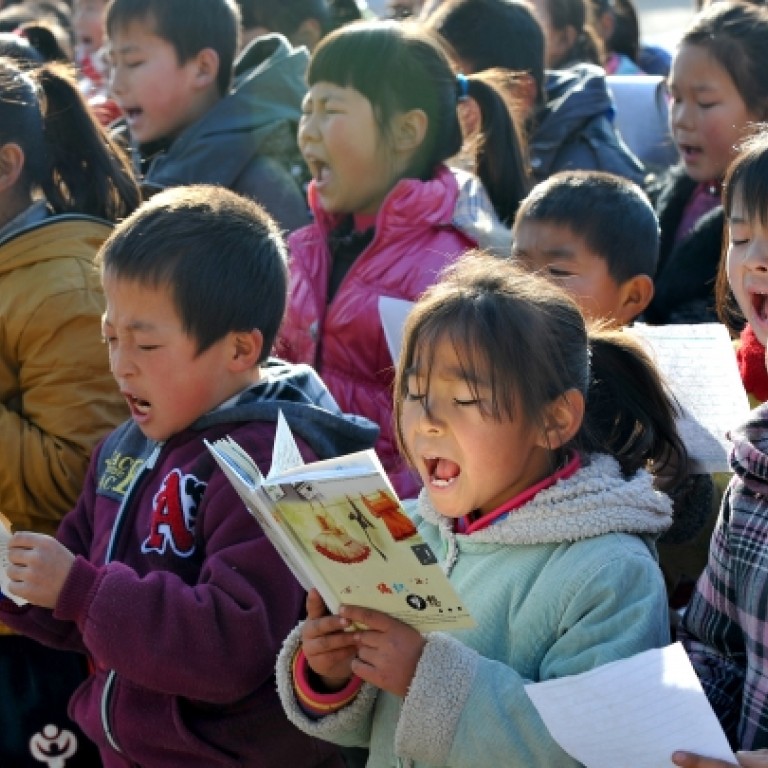

Tragic accidents just part of a hard life for China's 60 million 'left-behind children'

When Du Juan, who is now 18, was abandoned by her solo father at the age of nine, she could scarcely imagine she would one day attend high school. After 18 months studying at Shangdong Tancheng Datang School, Du was selected as one of 10 national “role model abandoned children” by the Care for Abandoned Children Fund in Beijing last year.

Her headmaster, Wang Yiyong, said the honour had changed Du - making her “much happier” and more motivated as a student.

Du is not alone. Nationwide, there are about 60 million children 'left behind' by their parents, the All-China Women’s Federation’s estimates in a recent survey. As their parents leave their hometowns to seek employment in cities, these children are often left in a state of insufficient care, if not dire poverty. The National Bureau of Statistics reported in 2010 that the number of migrant workers in China had exceeded 240 million.

“It’s a pity that these children lack the company of their parents at such a young age,” said Wang Yiyong. “It’s even a luxury to hear parents’ nagging their children,” he added.

An educator all his life, Wang, 50, has noticed that many students in his region - Tancheng county in Shandong province - were abandoned children. So in 2003, he started a special boarding school for abandoned kids. He said this allows students to study, eat, sleep and play like in a “large family”.

This year, his school developed into a full scale of kindergarten, primary school and secondary school with about 200 staff and teachers. It now has 1,460 students - over 70 per cent of them are abandoned children. Five years ago, the annual tuition of the boarding school was 4,000 yuan (HK$5,058). Now, it has risen to 8,000 yuan.

“It’s not that the parents can not afford to send their children to school. In fact, the boarding school is more expensive than an ordinary school,” noted Wang.

Wang’s view is shared by many experts, who stress that the issue of abandoned children is not about poverty. Rather it is about the need for some way to care for children whose parents are away.

Often left in the care of ageing grandparents or relatives, many children suffer from a lack of parental guidance, develop psychological problems; some fall victims to bullying, physical or sexual abuse, or even deadly accidents.

Two recent cases this year sparked great debate in China on the need to do more for abandoned children. On June 21, two young girls (aged one and three years) starved to death at their home in Nanjing City of Jiangsu Province. The girl’s father was in jail, while their mother, a drug addict, was missing. The local community had failed to help to save the lives of the little girls.

Then on June 27, two brothers and their sister drowned in a pond near their home village outside of Nanchang City in Jiangxi province. This occurred when their grandmother, who had been looking after them, went out. Unfortunately, the children’s parents were working in Guangdong Province, hundreds of kilometres away.

“These news headlines and tragedies generate negative feelings in our society,” said Tong Xiaojun, vice-professor at China Youth University for Political Science. “The country should urgently establish a child welfare system.”

Tong, who specialised in sociology and child welfare as child protection adviser for the Save the Children China Programme. She received her PhD degree at Denver University.

Tong said China did not have a child welfare system like the west. She said that there were large numbers of children at risk. These include orphans, as well as poor and abandoned children.

She said a child welfare system could monitor at-risk children and allow social workers to help when necessary. However, a major challenge in establishing it was enlisting the help of government departments - as well as families.

“These departments alone cannot resolve the issue… because it’s a national responsibility to protect our children,” Tong said.

She said NGOs could also play a role. The strength of NGOs such as Save the Children and international organisations like Unicef lay in their practical work with children. “A mutual benefit and collaboration between the state departments and NGOs will complement the child welfare system.”

Other things were also needed. “There is no national fund for these children,” said Wang Guohua, 50, secretary general of the Care for Abandoned Children Fund, which operates under the China Foundation for Culture and the Arts for Children.

Starting the fund three years ago, Wang Guohua has solicited money from private property owners and businessmen, even spending his own money to raise about one to two million yuan a year. “I aim to run the foundation…. it’s not a charity to give out cash,” he said. “What abandoned children mainly need is not money, but care and motivation”

That’s why he came up with the idea to elect “role model abandoned children” nationally. “Children need to have role models so they can grow up confidently. Despite their parents not being around, they can gain respect and recognition from others.”

The role model election programme is only a certificate to allow the children to come to Beijing. “No cash and gifts are involved. But the return could be significant,” Wang Guohua said.

For example, Du Juan’s strong level of motivation should encourage her to continue her studies, “even she won’t become a top student,” he said.

He also said too many parents were putting money before their children.

“A mistaken value exists in our society that parents can sacrifice their children in order to make money,” he said. “What’s the use of money, if children grow up to be unhappy and drop out of school?” he asked.

“Chinese parents should be educated to make a better life with their children,” said Helen Boyle, director of Migrant Children’s Foundation. She thinks it’s meaningless for children grow up without spending time with their parents.

As a former educator in Britain, Boyle, 55, started her non-profit organisation five years ago in Beijing in order to help abandon children learn skills such art, singing, drama and dancing.

“It’s like opening new doors for these children. New skills will bring new opportunities for their futures,” she explained.

She works with a few thousand students in nine schools around Beijing. Boyle said her programmes appealed to inquisitive children.

Besides providing them with skills, she and her 10 staff are raising donations to pay for the children’s medical expenses.

“Ultimately, children are not objects. They need guidance about life when growing up,” she said. Boyle added that as China expanded economically, it also needed to develop a child welfare system.