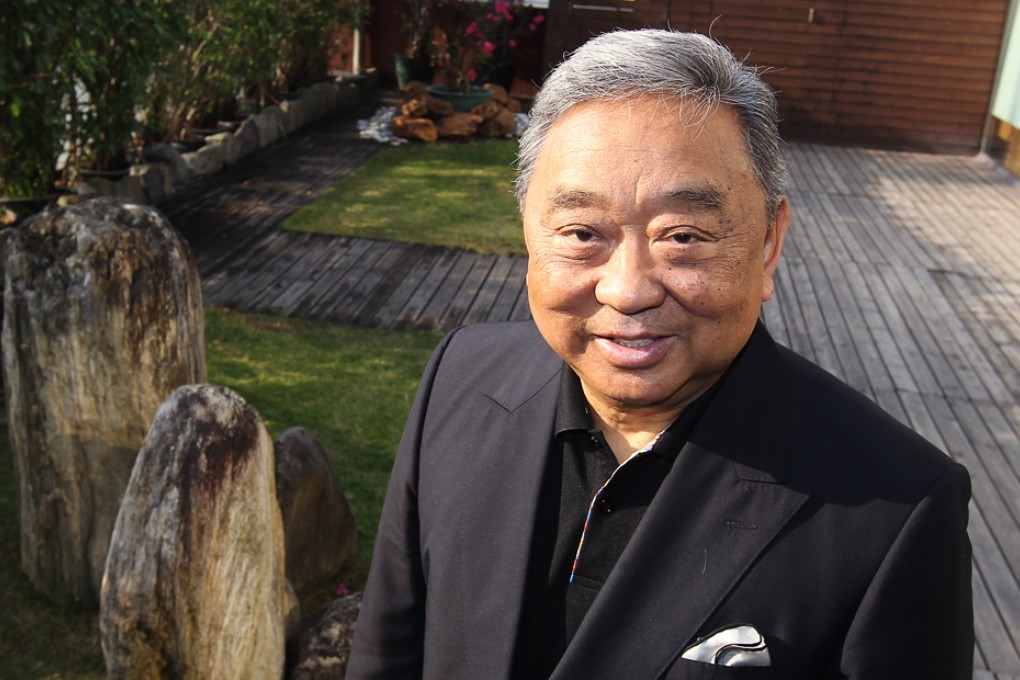

Businessman Ronald Chao funds Sino-Japanese student exchanges

A Japan-educated businessman has funded dorms at Chinese universities so local and Japanese students can experience what he did

In 1957, Ronald Chao Kee-Young, a child of China, went to study in Japan. He was 18 years old, born in Shanghai, raised in Hong Kong and knew no one in Tokyo.

“In 1957, Japan was very poor, poorer than Hong Kong and for sure poorer than Shanghai,” Chao recalls.

Emerging from consecutive wars, the Japanese society had a sense of defeat and “definitely had no time for any antagonism towards us foreign students”, he says.

What helped Chao adjust was living with 20 to 30 other Tokyo University students – half international and half local – in single rooms at the university’s international house. Chao learned about his housemates’ interests and their ambitions and quickly adapted to the campus.

It was easy, he realised, because Japan shares so much cultural heritage with China. And he found in Japan many of the traditions and values that were subsequently done away with during China’s Cultural Revolution.