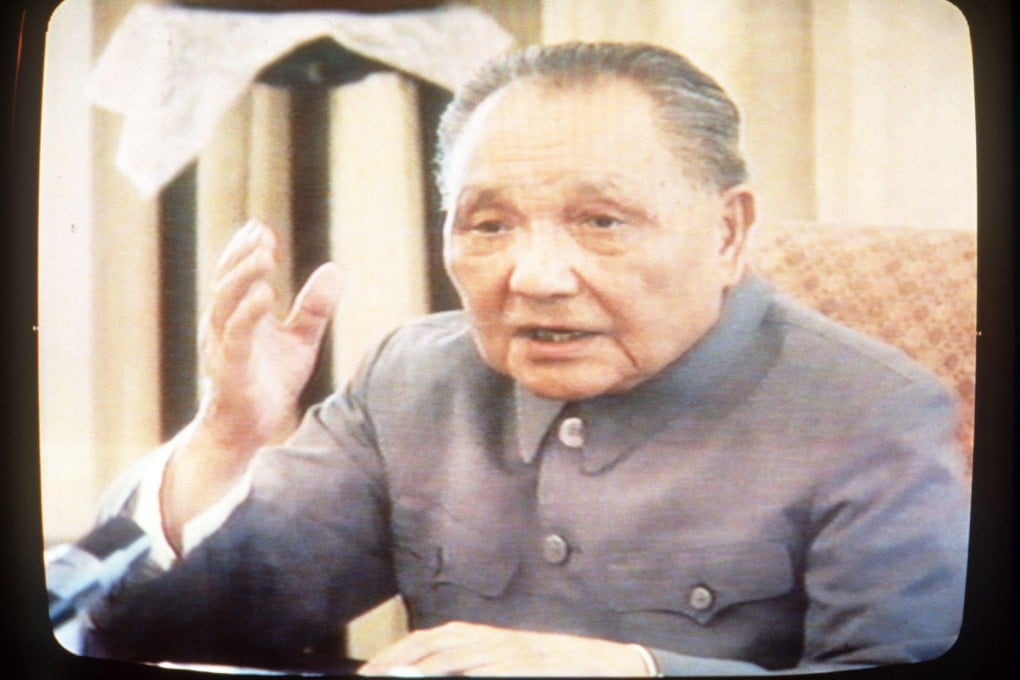

Deng Xiaoping's guiding principles are still in play today

President Xi Jinping's efforts to exert China's influence on the world stage mirror those of the former paramount leader, who would be 110 today

When Xi Jinping took office two years ago, he began flexing the country's military muscles and asserting Chinese involvement in regional affairs.

Yet analysts and China watchers say the philosophy of Deng, who would have celebrated his 110th birthday today, still guides the nation's foreign affairs - even when promoting China's interests has been viewed by other state leaders as bullying. Indeed Xi's style, some watchers note, takes cues from Deng.

Despite China's moves to control, for example, the South China Sea, these watchers say the nation is not ready to be a global leader in security matters - that the costs of doing so are too high.

"What we are seeing today is a China willing to be more proactive in achieving something it wants, such as defending claims in territorial disputes," said Taylor Fravel, associate professor of political science at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, in the United States.

But its wish to dominate had limits, he said. "International leadership is costly, and you can only lead internationally if you want to pay the cost for that. China is not willing to assume a leadership role in international affairs. It has its opinions, but it is not ready to be a leader in resolving problems."

Deng's diplomatic strategy emerged in the early 1990s, after the fall of the Soviet Union, as China was trying to steady itself amid an international furore over the bloody crackdown on Tiananmen Square protesters in 1989. Faced with international hostility, Deng focused on developing the nation's economy. Senior officials in the two post-Deng administrations led by Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao reiterated Deng's principles.