Genes make H7N9 nimble killer, study finds

Researchers are worried the bird flu strain could one day become a 'doomsday virus' capable of human-to-human infection

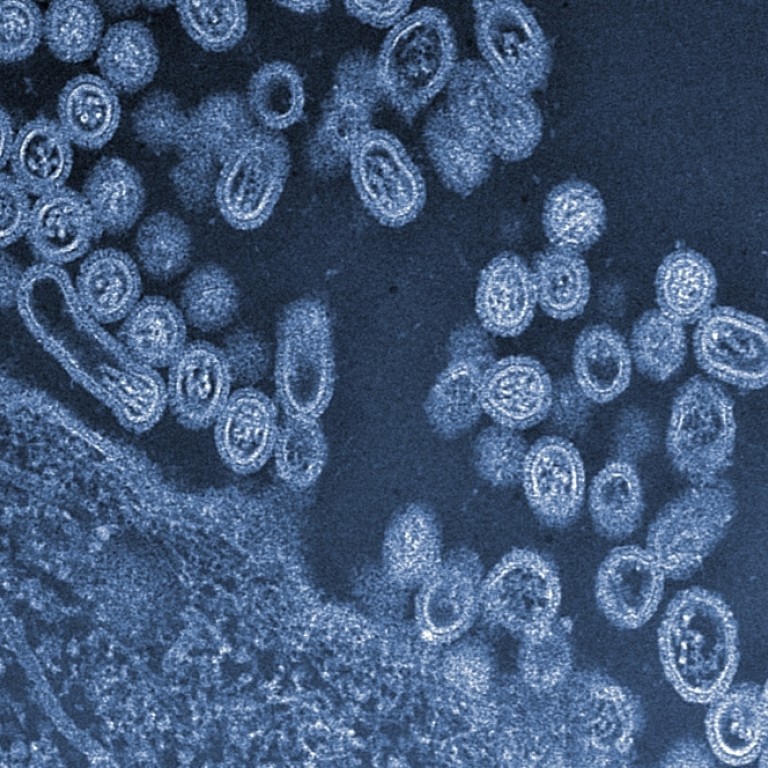

A deadly bird-flu strain first reported among humans two years ago is a swift transformer loaded with more genetic ammunition than previously thought, a mainland study reveals.

Researchers found that much of the virus' deadly power came from within, and at least half of its six internal genes are capable of causing illness in humans.

They also found that H7N9 changed rapidly after finding a new host. In some cases mutations that helped it survive better in mammals appeared in just four days, enabling the virus to spread quickly and inflict more damage inside the new host.

The study, by a team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences' Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, was published in the late last year.

Dr. Bi Yuhai, first author of the paper and the laboratory's technical director for flu virus, said H7N9 was probably the most elusive avian flu virus that scientists had encountered.

Since its emergence early in 2013, several key questions remain unanswered, including why it causes so few symptoms in birds - making early detection extremely difficult - and why it is so lethally active in humans. So far, at least 175 of about 460 people known to have been infected with the virus have died.

"In just under two years H7N9 infected as many people as H5N1 did in more than a decade," Bi said. "H5N1 was deadly to birds. H7N9 has almost no effect on birds. That is quite puzzling.

"Scientists have deep concerns about H7N9. Some fear it could be one of the most likely candidates to evolve into a 'doomsday virus' capable of human-to-human infection."

The researchers' experiments on mice suggested that H7N9's deadliness to humans came not only from HA and NA - the two genes on the surface of the virus that help it bind to and detach from host cells - but also three internal genes called PB2, NP and M.

The team, led by professors George Fu Gao and Frank Liu Wenjun, found that PB2 was likely the deadliest of the three. Repeated experiments showed that PB2 played a key role in causing a deadly immune reaction known as a cytokine storm in the mice.

Bi said the genes might lead to better treatments or a vaccine. "PB2 provides a clear, new target. Most vaccines and drugs today only target the two surface genes, but our study confirmed that targeting PB2 inside could also be effective," he said. But just getting this far has not been easy. "We launched animal experiments soon after we received the viral strains in April last year. The situation was grim and we fought like soldiers in a battle," Bi said

Cai Haodong, a specialist in infectious diseases with Beijing's Ditan Hospital, said the findings could play a role in prevention.

"I don't think they're significant for treatment but are meaningful for prevention," he said.

Li Lanjuan, who heads up an H7N9 team at the No1 Hospital Affiliated at Zhejiang University, said before the study was published that early treatment was vital. "We believe if a patient is treated with antiviral drugs at an early stage, the case rarely becomes severe. If they used a week later, the patient's condition is very likely to worsen," Li said .

In 2013, about a fifth of H7N9 patients treated by Li's team in Zhejiang died, well below the 39 per cent national average.