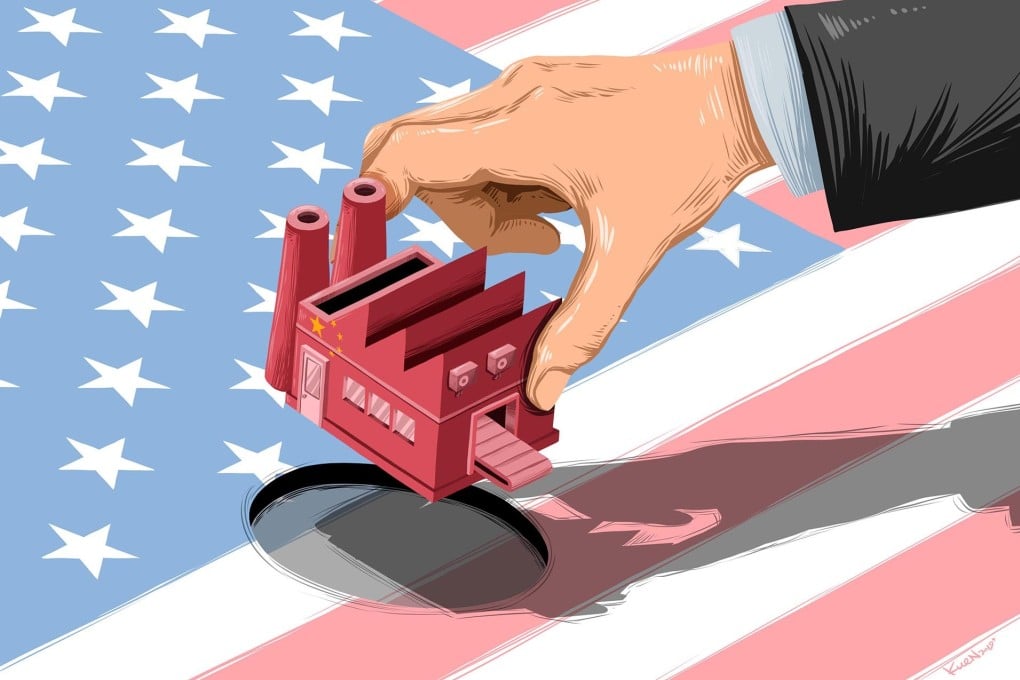

For Chinese firms in US, ability to navigate the cultural gap can determine success or failure

- Management styles, language skills and keeping expectations reasonable are just some of the challenges

- US and Chinese companies are both arrogant, experts say: having succeeded in their giant home market, they dive into others using a similar playbook

In 2014, two Chinese chemical companies outlined plans to build massive, multibillion-dollar plants in the United States, ultimately located within a few miles of each other in Louisiana. Five years later, YCI Methanol One has completed all major permitting and its plant is 60 per cent built, while Wanhua Chemical Group Co is still struggling with approvals.

The divergent paths reflect in part their different experiences navigating American business culture, risks and constraints, say company executives, local officials and citizen groups.

As Chinese companies venture overseas in growing numbers – becoming bigger targets for political, labour and security critics, seen most recently with Huawei Technologies and ZTE – their ability to navigate very different cultures is an increasingly important determinant of success.

A survey last month by the 1,500-member China General Chamber of Commerce-USA, an umbrella group of Chinese companies, identified cultural differences as the greatest problem members face in hiring and retaining American workers. US-China cultural divergence was among the top strategic challenges, it said.

“They don’t know what they don’t know,” said Charlie Yao, president and chief executive of YCI, the US unit of China’s Shandong Yuhuang Chemical Co, which is building a US$1.85 billion chemical plant in Louisiana.

“That’s the learning curve most Chinese companies go through, unknown to known. Typically it’s expensive in time or cost or opportunities they fail to grab.”