US sets sights on Harvard professor and universities over Chinese funding amid heightened fear of IP leaks

- Charles Lieber, charged with lying over his ties to China, received US$50,000 a month and US$1.5 million to start a research lab in Wuhan, prosecutors allege

- ‘This is a new front,’ one expert says. ‘This wake-up call is far louder because of who this person is, his ethnicity and the institution for which he works’

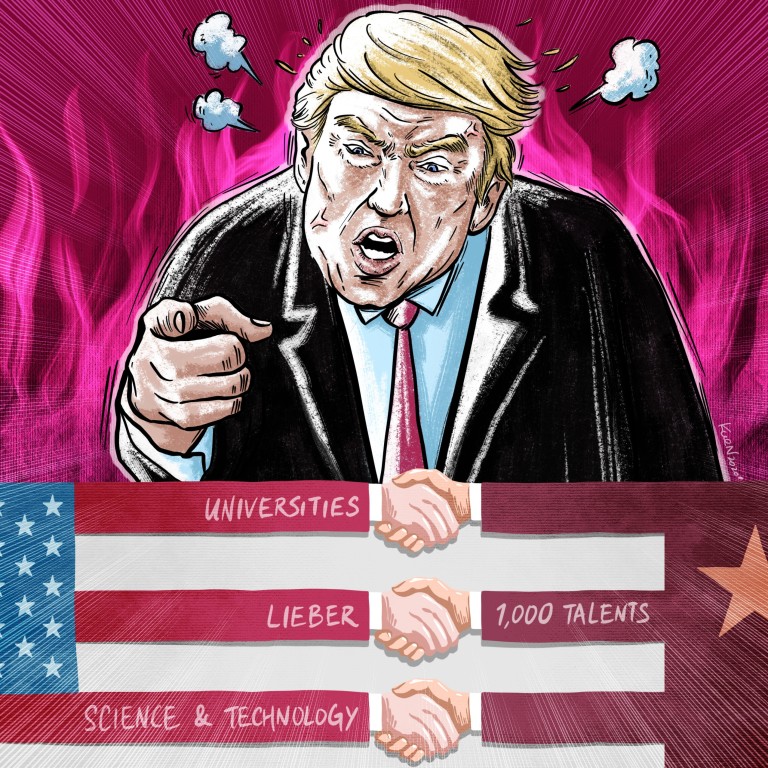

The Trump administration is adopting increasingly aggressive tactics in its bid to counter Chinese theft of trade secrets with the arrest of a prominent Harvard professor and high-profile investigations into top universities.

The move against one of the nation’s foremost scientists – Charles Lieber, chairman of the Harvard chemistry department – and the threat of criminal charges against Harvard, Yale and other prestigious universities over reporting violations has sent shock waves through the staid scientific establishment.

Unlike many other recent cases involving scientists of Chinese descent, Lieber is Caucasian. He and leading universities are also being accused of failing to disclose ties to China rather than actual espionage or industrial theft.

“This is a new front,” said Kei Koizumi, a science consultant and White House science and technology adviser in the Obama administration. “This wake-up call is far louder because of who this person is, his ethnicity and the institution for which he works.”

Anyone who has collaborated with Chinese colleagues could become a target. And once you become a target, it’s not pretty

“Now it affects everyone,” Koizumi added, “not just Chinese or other Asians like myself”.

But the Trump administration’s hardening stance is also calling into question the cost to American competitiveness if cowed researchers stop collaborating with top foreign talent, especially Chinese students and scientists.

“They don’t want to be the next headline,” said Toby Smith, the American Association of Universities’ policy director. “This could have a real chilling effect.”

Andrew Lelling, US attorney for the Massachusetts district, who brought the case against Lieber, said in an interview that the Justice Department did not go looking for this case. “We don’t pick the person, we pick their conduct,” he said.

Lelling acknowledged, however, that it has had a welcome deterrent effect. That has been magnified by US Education Department investigations into top colleges and universities for failing to disclose some US$6.5 billion in foreign gifts from China and other countries in violation of federal law.

The Lieber case has turned heads in part because of the huge sums China is willing to spend to attract top American talent.

According to the criminal indictment, Lieber received US$50,000 a month in salary, up to US$158,000 in annual expenses and more than US$1.5 million to start a research lab at the Wuhan University of Technology (WUT). This was reportedly arranged through Beijing’s Thousand Talents Plan, which was launched in 2008 to recruit foreign scientists.

“It’s enough to catch my attention, and everyone else’s,” said Koizumi. “You could say you misplaced a $5,000 travel budget to Beijing. But no one misplaces an entire lab in Wuhan.”

Universities’ inadequate disclosure of foreign gifts by universities appears more a result of lax reporting than wilful subterfuge, analysts said. But the evidence strongly suggests that Lieber, who has published more than 340 papers in peer-reviewed journals, knowingly hid his China links and funding, said Lelling.

According to the indictment, he received half the money in US currency and kept the rest offshore in a Chinese bank account. “We will help you change the cash for you when you come to Wuhan,” his Wuhan liaison wrote in 2017, the indictment says.

China mutes volume on Thousand Talents Plan as US spy concerns rise

It further claims that Lieber denied to Harvard in 2018 and subsequently to the Defence Department that he had worked with Beijing as a “strategic scientist” since 2012. The denial was relayed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which funds US$39 billion in American research annually.

“I lost a lot of sleep worrying about all these things last night,” Lieber wrote to a research associate in 2018, the charging document says. “I will be careful about what I discuss with Harvard University, and none of this will be shared with government investigators.”

Around the same time, he received US$15 million in NIH and Defence Department funding, it added.

Lieber’s expertise in nanotechnology, the manipulation of molecules, promises to revolutionise energy consumption, manufacturing and green technologies, potentially touching many strategic sectors of Beijing’s “Made in China 2025” blueprint to upgrade its economy.

He has been charged with one felony count of making false statements to US government agencies and faces up to five years in prison and a maximum fine of US$250,000. He has not yet entered a plea and is free after posting bail of US$1 million.

Lieber could not be reached, and his lawyers did not respond to a request for comment. WUT also did not reply; its website says “no content” under a “Foreign Expert Recruitment” heading.

‘New red scare’ shrouds US-China tech war as Trump cracks down on IP theft

Lieber’s arrest dovetails with Washington’s aggressive “China Initiative”, which began in 2018. Earlier this month, the Trump administration launched a “whole of society” counter-intelligence strategy to further guard against Beijing “stealing our technology and intellectual property in an effort to erode United States economic and military superiority”, the administration said.

Chinese intellectual property theft costs the United States up to US$600 billion annually, according to US trade representative figures. FBI officials characterise academia as a weak link in their efforts to stem the loss.

Academics and legal experts acknowledge the growing threat from China and admit they need more safeguards to avoid becoming a pawn in Beijing’s hands.

But turning universities into fortresses and jealously guarding basic research is counterproductive, threatening to undermine the economic leadership and innovation Washington seeks, they argue.

Academic watchdogs say they have long warned researchers that standards were tightening – foreign talent programmes were, until recently, viewed as prestigious – as Washington’s distrust of Beijing increased. But their warnings were often brushed off, they add.

“The Lieber case has been the biggest help we could possibly get,” said Mary Sue Coleman, the American Association of Universities’ president. “Before the view was, if you’re not a Chinese national, not a naturalised American citizen, it didn’t affect you.”

Fearing a new ‘red scare’, activists fight targeting of Chinese-Americans

Jolted into action, universities are scrambling to better define conflicts of interest, more closely monitor campus visitors, better integrate travel and integrity departments, handle grant applications through a single office and more carefully scrutinise foreign gifts.

Susan Wyatt Sedwick, a veteran grant administrator, said every major academic scandal led to more paperwork and funding restrictions that rankle scientists. “I think herding cats might be easier,” she said. “It’s like herding fish.”

Most bad actors tend to be motivated by money, ideology, ego or having been compromised, but the allegations of Lieber’s shadow lab and huge hidden payments set this case apart, she added. “I think this is more about ego than it is the money,” she said.

But academics also point to problems with US science.

The lure of doing cutting-edge, well-funded, basic research abroad without all the bureaucracy, while hardly an excuse, is attractive. This is especially true as the NIH and other funders shy away from high-risk, high reward projects, some critics add.

“We’re hearing a lot of complaints from US researchers that few percentage of grants get funded,” said Ali Nouri, president of the Federation of American Scientists. “But China also needs to play by the rules.”

A 2018 study by the Federal Demonstration Partnership, a group of grant-makers and recipients, found that scientists spent 44.3 per cent of their time on non-research administrative tasks, up from 42.3 per cent in 2012.

While the allegations against Lieber appear damning, the Justice Department may have its own agenda, said Temple University physics professor Xiaoxing Xi.

“In my own experience, what they say is not necessarily true,” he said. “We haven’t heard Charles Lieber’s side of the story.”

Arrested by FBI agents at gunpoint in front of his wife and daughter in 2015, Xi was charged with stealing cutting-edge technology to propel China’s semiconductor industry. A few months later, his case was dropped, apparently for insufficient evidence.

Heavy handed prosecutions, even if withdrawn, prevent top minds from advancing research and destroy reputations, said Xi, who is suing the lead FBI agent for bias and falsifying evidence.

“People on the street still think you’re stealing secret military technology,” Xi said. “Anyone who has collaborated with Chinese colleagues could become a target. And once you become a target, it’s not pretty.”

Others see Justice Department overreach, both in its focus on ethnically Asian scientists and in going after reporting violations without evidence of any secrets theft.

“You’re prosecuting a Harvard professor who incorrectly filled out a form without looking if there was actual technology transfer,” said Peter Zeidenberg, a partner with Arent Fox and a former federal prosecutor. “It’s taking a nuclear bomb to a situation that just doesn’t deserve it.”

The perils of being a Chinese scientist in Trump’s America

Zeidenberg, Xi and others say most cases can be handled without public shaming and harsh prosecutions. A prestigious National Science Foundation study released in December concurs, finding that many foreign influence issues “can be addressed within the framework of research integrity” without walling off core areas of science.

The NIH acknowledged in an email that funding applications can be burdensome but denied that the US punishes researchers for “honest mistakes”.

“When a grant application misrepresents, fabricates or falsifies information or data, it could be considered a serious violation,” it added.

Lelling put it more bluntly: “You can take money from the Chinese. But you can’t lie about it. If you lie, and it’s in the NIH grant-making process, it’s a crime.”

Although the FBI and Justice Department have long pursued economic espionage cases against China, they now have the resources and momentum to hit “critical mass”, he said.

FBI agents are investigating an estimated 1,000 China-related cases from its 56 field offices, Wray said, while US attorneys in five cities oversee their prosecutions. Law enforcement authorities have arrested 19 people in such cases since October, compared with 24 the previous year.

Lelling denied any administration bias in choosing which China-related cases to investigate and prosecute. Investigating Lieber’s many Chinese students without specific cause, for example, would be problematic, he said.

“This isn’t racial profiling,” the US attorney said. “You have a rival nation state made up almost 100 per cent of Han Chinese. Unfortunately there’s going to be tremendous overlap. We’re looking for the conduct, then the person.”

The Justice Department is cognisant of the resistance it has faced over China Initiative cases, and its very detailed 17-page indictment of Lieber is a conscious response to this scepticism, Lelling said. It is doing more outreach and hopes universities will voluntarily report suspicious circumstances linked to Beijing, he said.

Chinese overseas academic talent drive ‘fuelling suspicions’

The Lieber case has trained a spotlight on China’s Thousand Talents and other recruitment programmes. Matt Brazil, co-author of Chinese Communist Espionage: An Intelligence Primer, said it was only the latest of many increasingly well-funded attempts, dating from 1949 and earlier, to jump-start development by using foreign technologies.

One early coup saw Qian Xuesen, a noted rocket scientist in California, return to China in 1955 after being targeted during the anti-communist McCarthy era to become the father of China’s missile programme. But they also include such disastrous efforts as the Great Leap Forward, Brazil added.

He said Beijing now appeared to be directing more money and momentum toward foreign talent recruitment than ever, judging from recent indictments of Lieber and others. “If guilt is established, I suspect that this case would not be an outlier,” Brazil said.

Koizumi, who spent years in Sino-US negotiations at the White House, said he expected Beijing to shift tactics and recruitment methods given all the attention on its foreign talent programmes, adding: “They’ve always been pretty adaptable.”

Purchase the China AI Report 2020 brought to you by SCMP Research and enjoy a 20% discount (original price US$400). This 60-page all new intelligence report gives you first-hand insights and analysis into the latest industry developments and intelligence about China AI. Get exclusive access to our webinars for continuous learning, and interact with China AI executives in live Q&A. Offer valid until 31 March 2020.