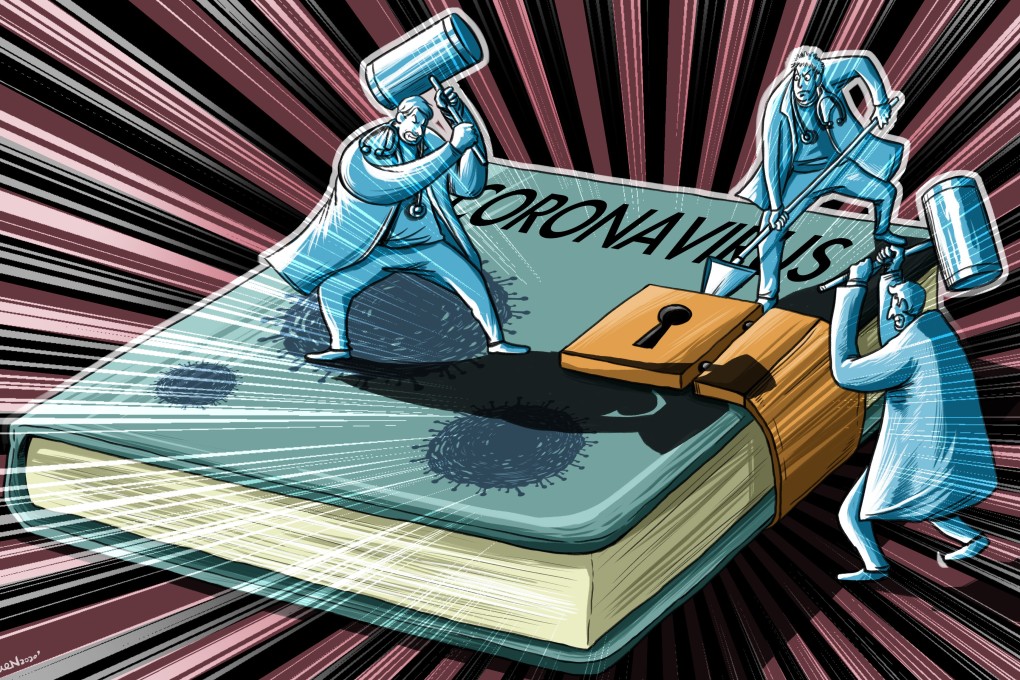

Will the coronavirus kill off the ‘dinosaur’ world of academic publishing?

- The deadly pandemic has brought back a long-running debate about companies profiting from the publication of research often freely supplied by the author

- As the biggest names in the business respond to academics’ demands to bring down paywalls, new platforms are getting fresh studies out to the public

The importance of that research was stressed on Friday when science authorities from 12 countries, including the US, Italy, and South Korea, released a statement urging corporate publishers of academic papers to make all relevant information openly and quickly available.

“[We] urge publishers to voluntarily agree to make their Covid-19 and coronavirus-related publications, and the available data supporting them, immediately accessible,” it said.

The statement not only signalled the urgent need for information as the epidemic kills thousands, but also flagged a behind-the-scenes conflict between academic publishers – such as Amsterdam-based Elsevier, and America’s Taylor & Francis Group – and scientists critical of publishing practices that lock leading research behind subscription paywalls.

While this isn’t a new argument, the Covid-19 pandemic is throwing a spotlight on how academic publishing works – an industry that some scientists say is based on a broken model and needs to be replaced.

Academic publishers have built highly profitable businesses by taking leading-edge scientific research, putting it to specialist review, and then selling it to companies, libraries and universities around the world.