Asians in the US least likely to get coronavirus infection despite racist assumptions of many, data suggests

- Data on Covid-19 infections and mortality in New York City broken down by ethnicity suggests Asians have the lowest infection and mortality rates of any group

- Similar figures from Los Angeles found Asians had the lowest infection rate among all groups

Cindy Song, a retired government employee living in Washington, saw the Covid-19 storm coming and hunkered down.

Alerted by Chinese friends on social media about the danger, by early March she had cancelled all travel plans and doctor’s appointments, was avoiding restaurants, acquaintances or supermarkets and wore masks and kept her distance on the rare times she ventured out.

“We already knew the disease, the virus, was really lethal, really bad stuff,” said Song, a native of Jiangsu province. “But whenever we got out and saw other people, and people we knew, they would give us this feeling that we were just overreacting.”

In one of many ironies involving the coronavirus, data suggests that Asian-Americans – who have weathered bigotry and attacks as suspected disease carriers – are the least likely to be infected or die from the scourge out of all ethnic groups in the US.

“This kind of xenophobia is never a rational thing, it’s based on stereotypes,” said Merlin Chowkwanyun, a sociomedical professor at Columbia University. “So it’s often not surprising to see that a place that you thought of for a long time to be this kind of cauldron of disease is actually not.”

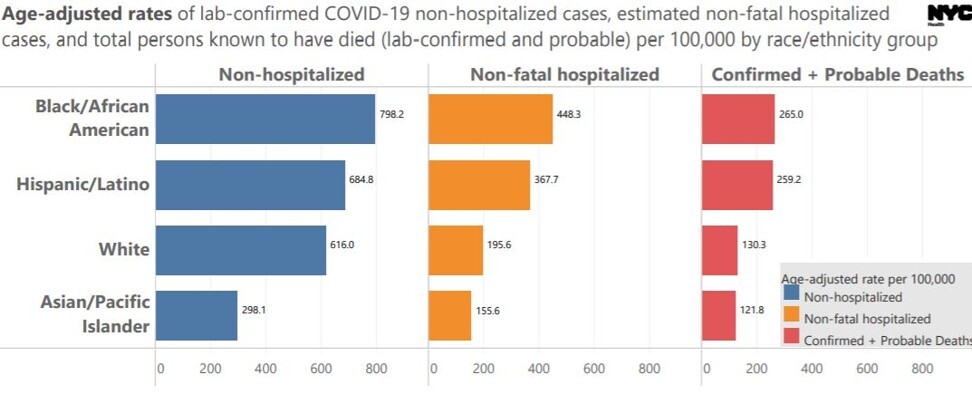

Available data on Covid-19 infections and mortality in New York City broken down by ethnicity suggests that Asians have the lowest infection and mortality rates of any group, including Caucasians, and often by a significant margin.

Asian deaths in America’s most populous and hardest-hit city as of May 14, according to the most recent data available, were 122 per 100,000 people compared with 265 for African-Americans, 259 for Hispanics and 130 for whites. Similar figures from Los Angeles found Asians had the lowest infection rate among all groups and a slightly higher death toll than whites.

A Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation study drawing on nationwide data found that minorities were hit disproportionately hard by the disease linked to lower incomes, greater job exposure and more pre-existing conditions. But people of Asian ethnicity had the lowest risk of serious illness of any ethnic group including the white majority.

Several factors may help explain this, say experts, even as they emphasise that the data is preliminary, and there is still a great deal that is unknown about the virus.

Covid-19 rate in Canada’s most Chinese city isn’t what racists might expect

One factor seems to be the “WeChat factor”, a reference to the omnipresent Chinese social media platform.

According to social scientists, knowing someone who contracted the disease is often a prerequisite for changing your behaviour, and Chinatown residents heeded warnings early contained in personal messages racing across the Pacific, in some cases even before Beijing tipped its hand.

“As early as January, before even the restaurants were dealing with low customer visits in New York City, many families and friends had already warned us about the tremendous need,” said Van Tran, an urban sociologist at the City University of New York. “This was not completely and honestly communicated by the Chinese government to the world.”

Reinforced by memories of the 2002-03 severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) outbreak, Asians stockpiled food early and many Asian groceries and other businesses started social distancing well before it was mandated by local authorities.

How British Columbia is beating the virus: luck and a shrewd Chinese community?

Asians also tended to cover up early, despite “maskaphobia” among the general population.

“Mask wearing was something done by Asians well before the beginning of this pandemic,” said Scott Frank, a public health expert at Case Western Reserve University’s medical school.

“There’s recognition that individual concerns should be subsumed for the good of the whole, rather than the more individualistic ethic that is oriented towards freedom and choice that is part of the white American privilege mentality.”

As discrimination, verbal and physical attacks mounted, many Asian-Americans avoided crowds out of fear of being singled out, also minimising infection.

Song said in recent weeks she had a Caucasian man spit in her direction and a grocery clerk tried to prevent her from touching vegetables. “I was afraid people would target me,” she said.

But the early shunning of Chinatowns that saw business devastated – despite high-profile campaigns by mayors to bring customers back – also meant that people-to-people contact in the ethnic enclaves was greatly reduced.

New York may never be the same again as extended shutdown clouds future

“You could say that it was a silver lining,” said Tran. “In the end, it truly saved not just the workers in the community, but also the businesses, and everyone else.”

A high percentage of Chinese living in New York City are recent immigrants, a group that tends to be more fit than Americans on average as their diet generally includes less fried food, red meat and sugar, epidemiologists say.

Their children tend to acclimate, however. “It’s called second-generation decline,” said Chowkwanyun.

By the third generation, often their high-blood pressure, obesity and diet are all but indistinguishable from the American majority, health experts say.

Socio-economic factors also helped Asians, experts said. While Asian-Americans in New York and nationally include many blue collar workers, on balance the community is better off economically and more educated than other ethnic groups.

That translates generally into more medical insurance, more savings to weather stay-at-home restrictions and larger living spaces to accommodate social distancing.

At the lower end of the ladder, Chinese, Hispanics and African-Americans tend to have poorly paid service jobs. But Chinese are more heavily concentrated in restaurants, which shut down early, while Hispanics and blacks more commonly work as drivers, government employees and supermarket employees on the front lines, Tran said.

And while those in the lower socioeconomic tier in all three groups tend to live in close quarters with several people, Chinese are more often in several-generation households, relative to Hispanics who are more likely to live with unrelated roommates coming and going for work, Tran said.

Asians on the whole also tend to more often be in the US legally, relative to the Hispanic community that is more likely to avoid hospitals to avoid detection. According to data from the Washington-based Migration Policy Institute, some 90 per cent of unauthorised immigrants in US counties with the highest concentration of migrants were from Mexico and Central America.

Some things worked against the Asian community, however. Many older first-generation Chinese who do not speak English avoided hospitals, given a cultural desire to die with family rather than alone and difficulties getting translation help in the overwhelmed medical system.

Raw data from Wisconsin, another jurisdiction to break out its statistics by ethnicity, shows that Asians suffered lower levels of infection and mortality than other ethnic groups except native Americans.

One possible explanation for Asians having a higher death toll than whites in Los Angeles may be that they tend to be second-, third- or fourth-generation Americans living in well-integrated suburban communities rather than ethnic enclaves, experts say. That often means they have fewer social media ties to China and less communal pressure to change their behaviour early on.

Public health experts emphasise that these are all early results with a better picture emerging in coming months.

“Put in a billion caveats,” said Chowkwanyun, including that “Asian” often covers very diverse communities, from Chinese and Koreans to Afghans and Pacific Islanders.

As Song remains at home under Washington’s social distancing guidelines, she reflects on the disquiet she has sometimes felt being Asian in the US during the pandemic. “I’m thinking of dyeing my hair blond, wearing big sunglasses and covering my face,” she joked. “It’s time for a change.”