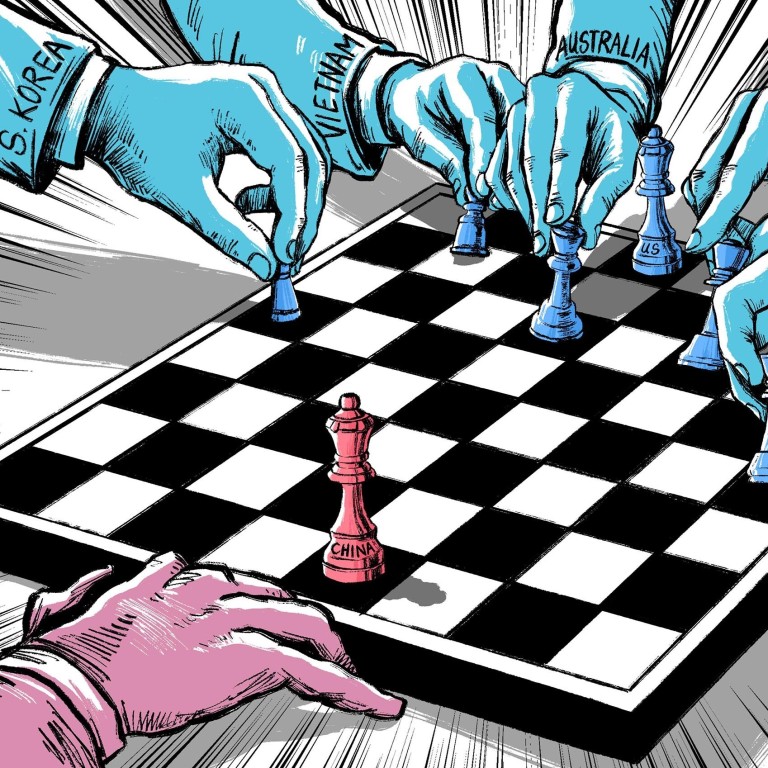

Asian states face stark choice in threat of China-US military clash

- Tensions between Beijing and Washington put pressure on friends and neighbours of both countries to pick a side

- Analysts examine how allegiances may align if the shouting match between the two powers becomes a shooting one

This is the last in a four-part series examining the growing tensions between China and the United States and how the situation could escalate into a full-blown military conflict. You can read parts one, two and three here.

While public comments by governments have made clear no country wants to see a direct clash between the two, military analysts say a conflict would force nations to choose sides. And most would go with the United States, because of existing treaties, alliances, and rivalries, they said.

Timothy Heath, a senior international defence researcher at the Rand Corporation, an independent US think tank, said the tensions were polarising the Asia region, and both Beijing and Washington were leaning on nations in Asia and elsewhere for support.

Some places, like the Philippines and Taiwan, were already using the tension to further their own interests, he said.

“If relations worsen and the risk of war becomes obvious to all, the countries most likely to side with the US in a confrontation with China include Japan and possibly Australia, Taiwan and the Philippines, depending on the circumstances of the fight,” he said.

“But the US-China relationship is still relatively stable and has not degenerated into open hostility.”

China might have fewer friends for support in a conflict, so Beijing might focus on reducing the number of countries that defected to the US, Heath said.

Russia could provide support and intelligence to China, but probably would prefer to watch from the sidelines as the two superpowers tore each other down rather than get involved, he said.

China seeks closer ties with Vietnam, neighbours as tensions rise with US

China formally upholds a “non-alignment” policy but has a close relationship with Russia, both having gone through Marxist-inspired revolution. The US has Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines and Thailand as allies in the Asia-Pacific region alone.

In a Pew research study in December, South Korea, the Philippines and Japan took the second through to fourth spots in a survey of world nations that regard the US as a more reliable ally than China. Only Israel was ranked higher. In the same poll, India and Indonesia came in at 12th and 13th, respectively.

Bilateral ties with these nations can boost US confidence and add to Washington’s leverage against Beijing, analysts say. The latest example is military exercises to counter China in Asia.

Earlier this month, the US conducted an air defence drill in the South China Sea, involving two aircraft carrier groups led by the USS Nimitz and USS Ronald Reagan, “in support of a free and open Indo-Pacific”.

02:32

Washington’s hardened position on Beijing’s claims in South China Sea heightens US-China tensions

Hu Xijin, editor-in-chief of Global Times, the national tabloid affiliated to the Communist Party's People's Daily, also waded in on Twitter where he called US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and three other hawkish US politicians a cold war “Gang of Four”.

In an earlier Tweet, Hu said China did not wish to engage in a cold war and accused the Trump administration of being the “most active” in starting one.

But a Rand report published in 2016, before Donald Trump’s inauguration as president, did flag warnings of the risk of conflict in the US-China relationship.

“Irrespective of their positions on the causes, merits, and favoured side in a conflict, countries, institutions and enterprises worldwide, fearful of economic harm, would appeal for an immediate end to Sino-US combat. But such views are unlikely to sway either belligerent,” it said.

How would other countries in Asia respond to a military conflict between China and the US?

“I personally believe that if something happens in Taiwan, South Korea will be a little more neutral than its partnership with the US would demand, since the country highly respects the idea of a one-China policy,” said Park Ihn-Hwi, professor of international politics at Ewha Womans University in South Korea.

“In the case of the South China Sea, South Korea will take a so-called ‘global standard-based’ principle, which is more beneficial to the US … if something happens in the South China Sea, South Korea will try to do something via international organisations to seek reliable diplomatic options.”

Trump’s G7 invitation puts China-South Korea ties to the test

Jay Batongbacal, director of the University of the Philippines Institute for Maritime Affairs and Law of the Sea, said the Philippines would first present itself as neutral, but then side with the US.

“Certainly the security sector would be concerned about sustaining collateral damage in such a conflict, and for sure [Philippine President Rodrigo] Duterte will hesitate, given his personal affinity for China, but I think the Philippines will abide by treaty stipulations if called upon by the US,” he said.

Grant Newsham, senior research fellow at the Japan Forum for Strategic Studies, said if things got to the point of an actual war, Tokyo was likely to get involved on the side of the US.

“It does seem to require a ‘crisis’ to get the Japanese government to move decisively on just about anything. And a war in Asia that potentially threatens Japan and its vital sea lanes and territory would presumably be an adequate crisis,” he said.

In the conflicting maritime claims in the South China Sea, Vietnam has been the most outspoken against Beijing’s activities in the area and may use a military clash between the US and China to press its claims, said Hu Bo, director of the Centre for Maritime Strategy Studies at Peking University.

China and US clash derails ‘new era’ for Beijing-Tokyo ties

Le Hong Hiep, a Vietnamese affairs expert from Singapore’s ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute, disagreed. “As far as Vietnam is concerned, Hanoi does not wish to see a military conflict between the US and China to flare up in the South China Sea,” he said.

“In case such a conflict does happen, Vietnam will try to stay neutral, but if push comes to shove, due to Vietnam’s own grievances against China in the South China Sea, Vietnam is likely to stay on the side of the US rather than China.”

India is yet another potential player in the struggle for influence and power that would emerge through any Sino-US warfare. China and India have already had a military clash this year at their contested border in the Himalayan region, resulting in the deaths of 20 Indian soldiers and an unconfirmed number of casualties among Chinese troops.

Srikanth Kondapalli, a professor of Chinese studies at the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, said Indian military doctrine focused on the Indian Ocean, but if the situation at the India-China border in the Himalayas worsened, there would be an incentive for India to get involved in any South China Sea clash.

The overriding concern of military analysts is how to prevent an armed conflict from spreading once it has broken out.

“Does such a regional interstate war escalate? Quite likely,” said Malcolm Davis, a senior analyst specialising in Chinese security at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute in Canberra. “US forces operating out of Japan, or Australian bases, would likely come under Chinese attack, so the conflict could escalate horizontally in that manner.

“How would Russia respond? The Chinese and Russians have exercised together and its uncertain whether Russia might exploit a US-China conflict in Asia to challenge Nato – so that’s a potential scenario for a ‘world war’. But that would be a worst-case scenario,” he said.

Additional reporting by Eduardo Baptista

Read part one of this series, which investigates whether China-US relations are drifting closer towards war; part two, in which war game scenarios suggest Beijing and Washington could ‘stumble’ into conflict in the South China Sea; and part three, examining how Beijing’s ‘red lines’ over Taiwan could lead to war with the US.