As US moves to renewable energy, wind turbines from Xinjiang may get caught in political tempest

- Xinjiang-based Goldwind has supplied material for a large US project that will deliver clean wind power for Microsoft, shipping records show

- As more information emerges about the suspected use of forced labour in the region, the US government has begun restricting trade from the area

At the new Las Lomas wind project in southwest Texas, French energy giant Engie’s wind turbines will soon deliver hundreds of megawatts of clean power to Microsoft.

The 48 turbines, scattered for miles near the Mexican border, are expected to be up and running in January, and they will help bring Microsoft closer to its goal of 100 per cent renewable energy by the year 2025.

When Engie and Microsoft announced their deal last year, they hailed it as an act of social responsibility: two corporations moving towards carbon neutrality amid the looming climate crisis.

But according to customs records, shipping data and corporate documents reviewed by the South China Morning Post, their business at Las Lomas may end up entangling them in another problem of an entirely different order.

Shipping records show that wind turbines at Las Lomas were supplied by an energy company partly owned by the Chinese government in Xinjiang, the far western region of China that is not only rich in oil and coal, but also in wind and solar energy production – and where Beijing is accused of detaining at least 1 million Uygurs and members of other Muslim minority groups in internment camps and subjecting them to political indoctrination and forced labour.

Xinjiang Goldwind Science & Technology Co Ltd, China’s largest wind turbine manufacturer, better known as Goldwind, also announced this month it had signed a separate deal with the powerful Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps (XPCC), the quasi-military entity that runs huge portions of the vast region’s economy, and was sanctioned by the US Treasury Department this year for human rights violations.

Experts say those connections – and the mere fact that Goldwind is based in Xinjiang – may prove troublesome for Microsoft and Engie, just as they already have for many other multinational corporations with supply chains that run through China’s far west.

Deadline passes for US firms to cut ties with Xinjiang megafirm

On one hand, the Las Lomas wind site is an example of US, Chinese and European companies taking action together, even while geopolitical tensions soar, to reduce carbon emissions and help the environment.

On the other, they are companies whose supply chains run through a part of China where there has been widespread international condemnation, including from a UN high commission in Geneva over human rights violations reported to be taking place there.

“If someone is coming to me and saying, ‘I’m importing something from this region’, I’m telling them, you should review your supply chain and assess potential risks, and we need to feel comfortable that you don’t have forced labour in your supply chain because [the US government is] going to be looking at it,” said Olga Torres, managing member of Torres Law, which specialises in trade and national security.

“If you don’t do these basic things, you’re being irresponsible,” she said.

As more information on Xinjiang’s human rights situation has emerged from eyewitness accounts, satellite imagery, customs records and Chinese official documents, the US government has begun to restrict trade from the region.

Analysts say some of the suspected forced labour, which Beijing denies is occurring, may be linked to the Chinese government’s “poverty alleviation” programme, while some may be connected to the camps.

Most of Washington’s attention has been on industries related to cotton and textile production, which Xinjiang has come to dominate in recent years, or surveillance tools, which reports say constantly monitor the region’s Uygur population.

But according to the Chinese government’s trade data, Xinjiang’s biggest export to the US this year is not shoes, clothes or cotton – it is wind turbines.

US sanctions Chinese entity, individuals over Xinjiang ‘human rights abuses’

Under current policy, there is nothing stopping a wind project in the United States from sourcing equipment from a company based in Xinjiang, as long as no sanctioned businesses are involved.

That could change if the US government decides to do so, Torres said, leaving companies to either find ways to shift their supply chains or shut down their operations entirely.

On July 1, the US State, Treasury, Commerce and Homeland Security departments jointly issued a business advisory warning companies to “be aware of the reputational, economic and legal risks” of getting involved with firms linked to human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

That same month, the Trump administration announced Magnitsky Act human rights sanctions against the XPCC and some of its top personnel. The sanctions went into full force at the end of November.

Under the sanctions, doing business with the XPCC could lead to financial and criminal penalties for US firms, depending on how aggressively the Treasury Department decides to enforce the law.

Goldwind has cut deals with the XPCC but is not owned by it, Chinese corporate records show, making it unlikely that these specific sanctions would ensnare US companies that do business with China’s biggest wind turbine manufacturer.

One of Goldwind’s major shareholders, Three Gorges Renewables, a state-owned enterprise, is involved in multiple wind power development projects with the XPCC. Among them, it will rent 1.5 million square metres of land for free from the XPCC – the size of more than 200 soccer fields – until the year 2043, in an area of Xinjiang called Beitashan Pasture, about 400km (250 miles) northeast of the provincial capital, according to a company prospectus released in March.

On December 12, Goldwind signed a “strategic cooperation framework agreement” with a unit of the XPCC based in Beitun, a city in northern Xinjiang that is run by the XPCC itself. The deal was worth about US$2.5 million.

That came just one week after the XPCC’s powerful Communist Party secretary, Wang Junzheng, declared that the energy industry was “uniquely important for the XPCC’s development”.

China says no let-up in Xinjiang crackdown

Beyond the XPCC sanctions, a bill that some members of Congress tried to pass this year could have done much more to potentially block the Xinjiang wind industry from entering the United States. The Uygur Forced Labour Prevention Act would have cut off all supply chains that run through Xinjiang to the US unless the importers could prove their goods had no connection to forced labour.

Experts say proving that would be no easy task because supply chain audits are so difficult to conduct in Xinjiang, a result of pervasive government surveillance in the region.

Among the parts of the process an auditor would need to inspect are those involving hard manual labour: wind turbine construction often involves the forging of steel and fibreglass. Workers also need to wind up coils of wire inside the turbines’ electric generators.

A Goldwind representative said the company operated “in compliance with international business rules and local laws and regulations in the countries where it operates”.

She said the company has “manufacturing bases” throughout China, “all of which play an important role in the supply of Goldwind’s wind turbine products to the domestic and international markets”.

“Among them, the manufacturing bases for seaborne exports are mainly located in the eastern coastal areas,” she added.

01:57

US House passes Uygur law demanding sanctions on China over human rights abuses in Xinjiang

Despite broad bipartisan support, the bill targeting forced labour in supply chains passed the US House of Representative by a vote of 406-3 but failed to reach the Senate floor amid a lobbying campaign by corporations and industry groups. Representative Jim McGovern, a Massachusetts Democrat and the bill’s sponsor in the House, has said he will introduce it again next year.

Lobbying disclosure records showed that Engie, which is 23.6 per cent owned by the French government, hired a firm to lobby Congress about the bill. After the Post contacted the company for comment, an amended disclosure form was filed that removed the reference to the legislation.

The disclosure records also show that the Consumer Technology Association, of which Microsoft is a member, lobbied Congress on the bill.

Engie and Microsoft did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

“As a company registered in Xinjiang, Goldwind keeps a close eye on the legislation and actions related to Chinese companies in the United States,” the Goldwind representative said. “We are monitoring and evaluating the possible impact on our business in the United States. Goldwind’s current business in the United States is conducted in a normal and orderly manner.”

Goldwind’s expansion in China and overseas has come with the support of some of China’s most powerful people and organisations.

US delays human rights sanctions on Xinjiang Production and Construction Corps

In 2016, while touring a hi-tech expo in Cairo, Chinese leader Xi Jinping “highly recommended” Goldwind to Egyptian Prime Minister Sherif Ismail. Seven years earlier, then vice-president Xi visited Goldwind in Urumqi, Xinjiang’s capital city, and said the company should be a “national brand”.

Goldwind’s CEO and founder, Wu Gang, was a deputy of China’s National People’s Congress, the largely rubber-stamp parliament in Beijing, from 2012 to 2018, according to Wu’s biography on the company website.

Through multiple layers of state-owned companies and their subsidiaries, Goldwind’s largest shareholder is a state entity known as SASAC, which is in charge of the government’s assets.

The establishment of Goldwind in 1997 was initiated by Xinjiang Wind, a state-owned enterprise, which provided 90 per cent of the capital. In 2010, Three Gorges Renewables – a subsidiary of the Three Gorges Group, which holds 43.33 per cent of Xinjiang Wind’s shares – became the second largest shareholder of Goldwind, company files show.

00:49

Chinese truck makes dramatic delivery of huge wind turbine blade

Goldwind made a net profit of 2.2 billion yuan (US$336.4 million) in 2019, and its net profit in 2018 reached 3.2 billion yuan. It has also expanded abroad from its roots in Xinjiang.

In 2017, Goldwind’s Wu said Xinjiang should be the “electricity hub” for China’s Belt and Road Initiative, Beijing’s programme to build infrastructure projects in countries around the world. Goldwind has undertaken various belt and road projects throughout Asia and in September signed a new memorandum of understanding with Standard Chartered in Singapore to build a “strategic cooperation relationship” in Southeast Asia.

In August, Goldwind announced that it had received a US$10 million grant from the New South Wales government in Australia for an energy project there, amid rising tensions between Beijing and Canberra.

In 2018, Wu wrote that Engie, the French energy company, was a “major international client”.

In shipping records compiled by the firm S&P Global Market Intelligence, Goldwind’s biggest client listed this year has been the Las Lomas site in Texas. Its records for Las Lomas list Goldwind as the only supplier.

US, China may cooperate on Covid-19, climate change under Biden

Goldwind has an American subsidiary, Goldwind Americas, based in Chicago. Its finance arm, Goldwind Capital, invests in wind projects around the US as more states rush to embrace renewable energy, despite US President Donald Trump’s statements ridiculing the industry.

In a speech last year to congressional Republicans, Trump called turbines “graveyards” for birds and suggested the noise from them caused cancer (the American Cancer Society said that was not true).

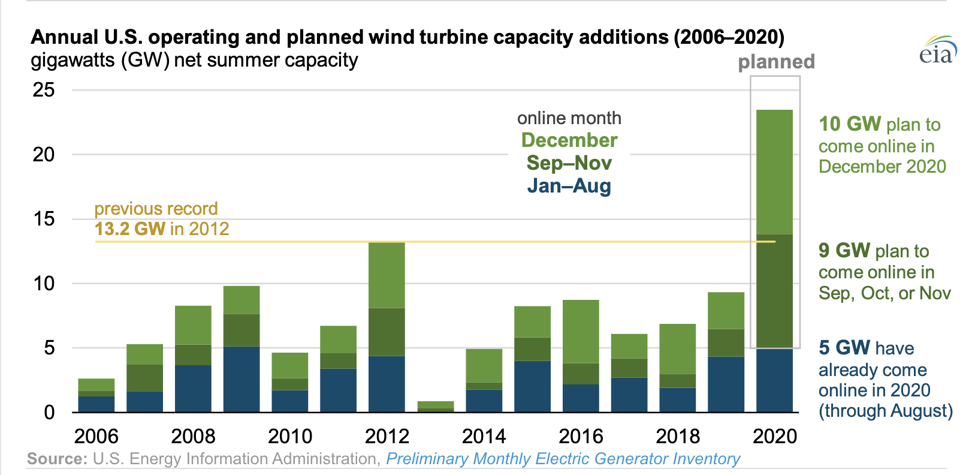

Yet the industry is expected to keep growing rapidly in the US.

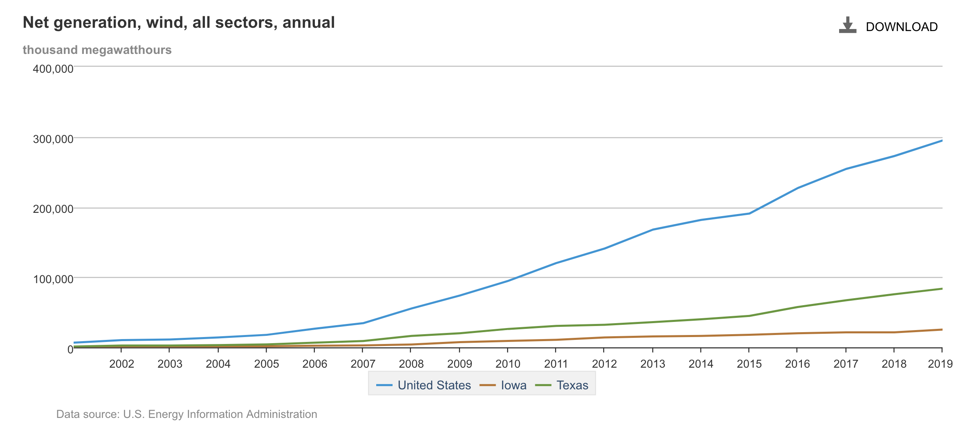

Wind power is the largest segment of renewable energy in the United States, accounting for 7.1 per cent of total domestic generation in 2019, followed closely by solar, at 7 per cent, according to US government data.

US wind farms generated 295 million kilowatt hours of electricity in 2019, a fourfold increase over a decade, and the Bonn-based World Wind Energy Association pegged growth in the global wind energy market in 2019 at more than 10 per cent, up from 9.3 per cent a year earlier.

The US Bureau of Labour Statistics says wind turbine service technicians will be the fastest-growing job in the country through the next decade.

“Wind power is well on its way to becoming a conventional source of power in the US; in some regions, and on some days, it can account for more than 70 per cent of power produced, and on an annual basis is likely soon to exceed 10 per cent of production nationwide,” said A.J. Goulding, a principal at London Economics International, an energy and infrastructure consulting firm.

“Wind power component supply is a global business, and Chinese manufacturers are a key part of the wind power supply chain,” he added.

‘Ready on day one’: Joe Biden unveils climate team

Whether that growth includes a company based in Xinjiang may depend on what the new US Congress and the Biden administration do next year.

“There’s nothing that prohibits you from importing from that region, but obviously there’s a lot of noise coming from that region,” said Torres, the trade lawyer. “I would still be looking at, where are the factories located? Are we close to any internment camps? Any industrial estates involved in ‘poverty alleviation’ efforts?”

“It’s a responsibility towards your shareholders, to your investors,” she added. “If you get into any kind of situation where your products all of a sudden cannot be imported, that could be devastating for companies.”

Additional reporting by Robert Delaney