Chinese parents fear children’s English skills will suffer as schools cut back on language classes and tutors face crackdown

- Reforms designed to reduce the burden on pupils have worried parents who fear they will reduce their ability to communicate with the outside world

- Cuts to language teaching also come amid growing nationalist sentiment and a national debate about how useful it really is to learn English

Although their options are further limited after a crackdown on private tutoring, they will not easily be deterred.

“Many parents, those who deem English as an important tool to help you connect with the world, are figuring out solutions to offset the impact,” says Stella Zou, who runs a 500-member social media group for those who share her concerns.

Last year, she said her daughter took four English classes a week, supplemented by four further online sessions with US-based teachers through a private educational platform.

03:22

Crackdown on private tutoring leaves industry, students and parents drawing a blank

“English seems to be the subject hit the hardest by the education reforms,” she sighed.

Over the summer, the 41-year-old business owner bought a bookshelf worth of English language textbooks – ranging from the Reading Explorer series by National Geographic Learning to Wonders by McGraw-Hill Education. She now plans to teach her eight-year-old daughter herself.

However, they also come amid a growing debate about whether most Chinese people need to spend so much time studying the language – fuelled in part by a rising tide of nationalism that has seen some prominent figures warning against exposing people to foreign ideas.

Chinese government to crack down on underground private tutoring market

There was no national order to cut the number of school hours spent learning English, but many did so as schools across the country adjusted their curriculums to comply with the order.

For example, many schools in Beijing, Shanghai, Sichuan and other provinces have cut back on language teaching in favour of more time spent on sporting and artistic activities.

Shanghai, the most international city on the mainland, even said last month that pupils would no longer be taking final English proficiency examinations to ease the academic burden placed on students.

It follows a decision in February by the northeastern province of Liaoning to lower the maximum number of marks available from English in the university entrance exam, thereby reducing its importance for achieving a good overall grade.

In July, new rules were introduced that ordered tutoring and education services firms to convert to non-profit status, banned them from offering classes in the core curriculum subjects – Chinese, maths and English – during weekends and school holidays, and prohibited the use of foreign curriculums or classes held with foreigners based outside the country.

Online sessions with tutors outside China – once a regular feature of Zou’s daughter’s life – are now banned.

The Beijing-based start-up VIPKid, which has now said it will stop offering such services, said it had employed almost 90,000 teachers in the US and Canada and almost a million Chinese students had signed up for its classes.

“The government seems to have decided that English is not so important,” Zou said, “I was so surprised by the moves. When I was a student, English was widely regarded as an essential subject in China’s opening up to the world.”

China kills almost 300 partnerships with foreign universities after tutoring ban

China has been encouraging its people to learn English since the opening-up policy began in the late 1970s and two decades later the subject formed part of the primary school curriculum.

In 2001, the Ministry of Education issued guidelines, urging primary schools in all but the most remote parts of the country to ensure English classes were offered no later than the third grade to “modernise education to face the world and meet the demands of the future”.

But this trend appears to have peaked with the 2008 Beijing Olympics, which offered China the opportunity to showcase the dramatic changes of the previous decades.

01:15

Anxious parents in China climb fence to check on children in school

In March 2019, Hua Qianfang, an influential “patriotic” blogger who was once invited to attend an arts and culture meeting with President Xi Jinping, sparked a heated debate online with a social media post that argued that studying the language was “a trash skill for most Chinese” and warned “a Western language will lead to a Western way of thinking”.

In March this year, Xu Jin, a member of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, the main national political advisory body, suggested that English should be removed as a core subject in primary and junior secondary schools and should not be compulsory in the university entrance exam, or Gaokao.

He argued that making the whole population learn English was a waste of time and resources, saying it took up about 10 per cent of class time but official figures showed it was useful for less than 10 per cent of working graduates.

The proposal triggered a national debate. A poll for China Youth Daily highlighted the divisions with the majority – more than 110,000 respondents – opposing the idea and saying it should be taught from an early age to enable China to compete with other countries.

China must watch for signs of rising nationalism, warns ex-top official

However, around 100,000 people supported the proposal and said it would be better to spend more time studying Chinese language and culture.

Sun Ning, 34, a railway engineer in Beijing, said he welcomed the move to cut the number of hours spent learning English. “Many people don’t use English much at work. When we need it, we can resort to smart AI-enabled devices for translation. It’s very convenient,” Sun said.

In Beijing, Zou said she was going to hoard textbooks for fear they would be removed from the open market if the authorities further tightened their ideological controls.

“I’ve spent tens of thousands of yuan on these books,” she said. “It’s not only about language. More importantly, by learning a foreign language, we can understand the Western mindset and develop the skill of critical thinking, which you never learn on mainland campuses.”

02:53

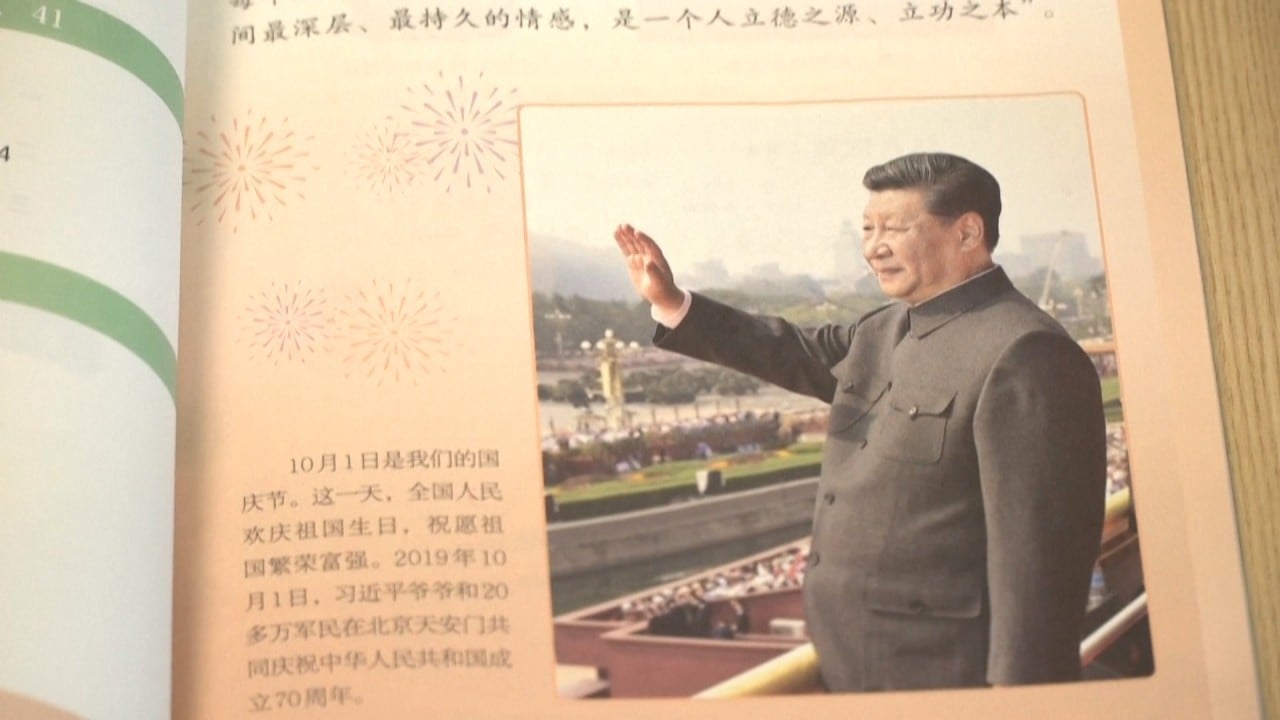

Xi Jinping Thought to be introduced in China’s classrooms

But not everyone has the time or the skills to teach their children themselves.

Yuan Jie, 36, a mother from a remote part of Sichuan, said cutting back on English would put her 10-year-old son at a disadvantage.

“We live in a fourth-tier county, where children’s education depends heavily on the public school system,” she said.

“My son’s English classes have been cut from three a week to two this semester. I’m so worried that he will lose the edge in future competition with his peers in big cities, but I don’t know what to do.”