As Joe Biden’s ‘Summit for Democracy’ convenes, questions arise about how ‘democracy’ is defined

- Beijing has condemned the event and expressed particular anger that Taiwan is among its 110 invitees

- Although China is not specifically mentioned in summit documents, it is a clear object of the proceedings

But the intervening months have not been kind to the administration as it prepares to host, starting Thursday, a two-day virtual Summit for Democracy. Despite a roaring stock market and the passage of massive bills covering pandemic relief and infrastructure, US democracy is on its heels. Voters are irritable, the electorate is mired in partisan battles and the nation is grappling with early January’s assault on the Capitol.

“The democracy summit is an idea whose time expired on January 6, 2021,” said Jeffrey Moon, head of China Moon Strategies and former US consul general in Chengdu. “Uncomfortable topics, a lack of commitments, problems with invitees and outcomes – all highlight contradictions in US policy.

“These are exceptions to the rule, but those that have an interest in pointing them out are going to do so.”

China and Russia, both pointedly excluded from the meeting, have just such an interest. In a rare joint note late last month in the conservative National Journal, Beijing and Moscow condemned the US summit as an “evident product of its Cold War mentality” aimed at fuelling ideological confrontation and creating new divisions.

Beijing has expressed particular anger over the inclusion of Taiwan among the summit’s 110 invitees, especially after Taipei signalled its acceptance with a statement that started, “Our country’s invitation … ” Beijing considers the self-governed island to be a renegade province, to be reunified by force if necessary.

On Tuesday, a senior administration official said Taiwan’s invitation was premised on its being a “leading democracy”, “powerful example” and pioneer in fighting disinformation. But the island will participate in keeping with the “one-China” policy, the official added.

The Biden administration has laid out three main objectives as part of the meeting’s bid to “renew” democracy: countering autocracy, fighting corruption and supporting human rights.

Is Biden’s democracy summit the start of a new world order?

The meeting comes as China, Russia and other autocratic governments are quick to promote the advantages of their governance models, pointing to their ability to move decisively and avoid the political infighting seen in democracies over everything from Covid restrictions and policing to voting rights and social issues.

“China, I won’t say its winning the PR war, but it’s very competitive,” said Sarah Kreps, a government professor at New York’s Cornell University and former military analyst.

“Some 90 per cent of the Netherlands has Western vaccines, but it’s got higher levels of Covid than in the history of the pandemic. They’re trying to poke holes in the democratic system.”

With ideology rapidly joining trade, defence and diplomacy on the long list of US-China irritants, the civic group Halifax International Security Forum has produced a “handbook for democracies”.

It touts the guide as a wake-up call given the democratic world’s “miscalculation of historical proportions”, namely that China’s political system would become more like a liberal democracy as it grew wealthier.

“There is a global competition in value systems,” said Robin Shepherd, the group’s vice-president and author of the handbook, which calls on democracies to counter Chinese Communist Party efforts to remake the global order.

“They don’t respect weakness and all they do when they see it is exploit it. That’s not to say we want to be reckless,” Shepherd said. “The danger of skirmishes in the South China Sea is out of control.”

China puts on its own ‘democracy forum’ in countdown to Biden’s summit

Some have criticised this week’s summit as a public relations exercise thrown together without great preparation, short on civic group participation, with a questionable and overly long list of invitees that weakens its focus.

The administration would better bolster its global status by filling many of its empty diplomatic posts rather than by holding conferences, said Nicholas Cull, a public diplomacy professor at the University of Southern California journalism school.

While some of these require Senate confirmation, many do not. According to the Partnership for Public Service, the Biden White House is level with the Trump administration in filling positions but slower than presidents Barack Obama or George W Bush.

To bolster the substance of this week’s events, the administration has urged delegates to announce commitments, reforms and initiatives aimed at defending democracy – without providing details – preferably those that can be measured at a follow-up “year of action” summit next year.

Although China is not specifically mentioned in summit documents, it is a clear object of the proceedings.

“What the Biden administration is trying to do is thread the needle between the need for democratic renovation at home and at the same time trying to restore our standing abroad,” said Ted Piccone, a Brookings Institution fellow.

“It’s not all about China. But it’s a lot about China.”

Days before the summit started, Beijing held its own “democracy forum” and issued a white paper, arguing that the West had no monopoly on democracy. China has eight minor “democratic” parties; in practice, these answer to the CCP.

“Democracy is the right of all peoples, not a monopoly of a few nations,” said Liu Pengyu, Chinese embassy spokesman in Washington. “Whether a country is democratic or not should be decided by its people, not by outsiders.”

Singapore’s non-invite to democracy summit ‘not a judgment’: US

In a follow-up report released on Sunday, Beijing criticised American democracy as a dysfunctional “game of money politics” run by elites.

China’s arguments against democracy and the superiority of its system tend to focus on performance metrics – that it has elevated hundreds of millions from poverty, crushed Covid-19, built exemplary infrastructure – whereas Americans focus more on principles, rule of law and individual rights, said Neysun Mahboubi, a scholar at the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for the Study of Contemporary China.

Authoritarian governments, outwardly confident in their systems, often feel the need to claim they are democratic, Mahboubi said, with some Communist nations going so far as to embed the term in their name.

Thus North Korea is formally known as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) while the former East Germany called itself the German Democratic Republic.

“You can say China is participatory, responsive, more nuanced than sometimes appreciated. But it’s very difficult to say a one-party state without elections, that isn’t transitioning to political reform, is a democracy,” Mahboubi said.

“But it is fascinating that they are pushing that line. It demonstrates the power of the idea, the notion that people should have some ability to change leaders if they’re not performing well, and not through revolution but peaceful means.”

The US, for its part, finds itself trying to walk a fine line with this conference, analysts said. Invitees include several countries with questionable democratic credentials, including Pakistan, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iraq and the Philippines, which has a history of extrajudicial killings. And the summit’s large size threatens to dilute any message.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace notes that more than one-third of the invitees are either not free or partly free based on Freedom House rankings.

And a Pew Research poll of respondents in 17 countries last month found just 17 per cent considered the US a good model for democracy.

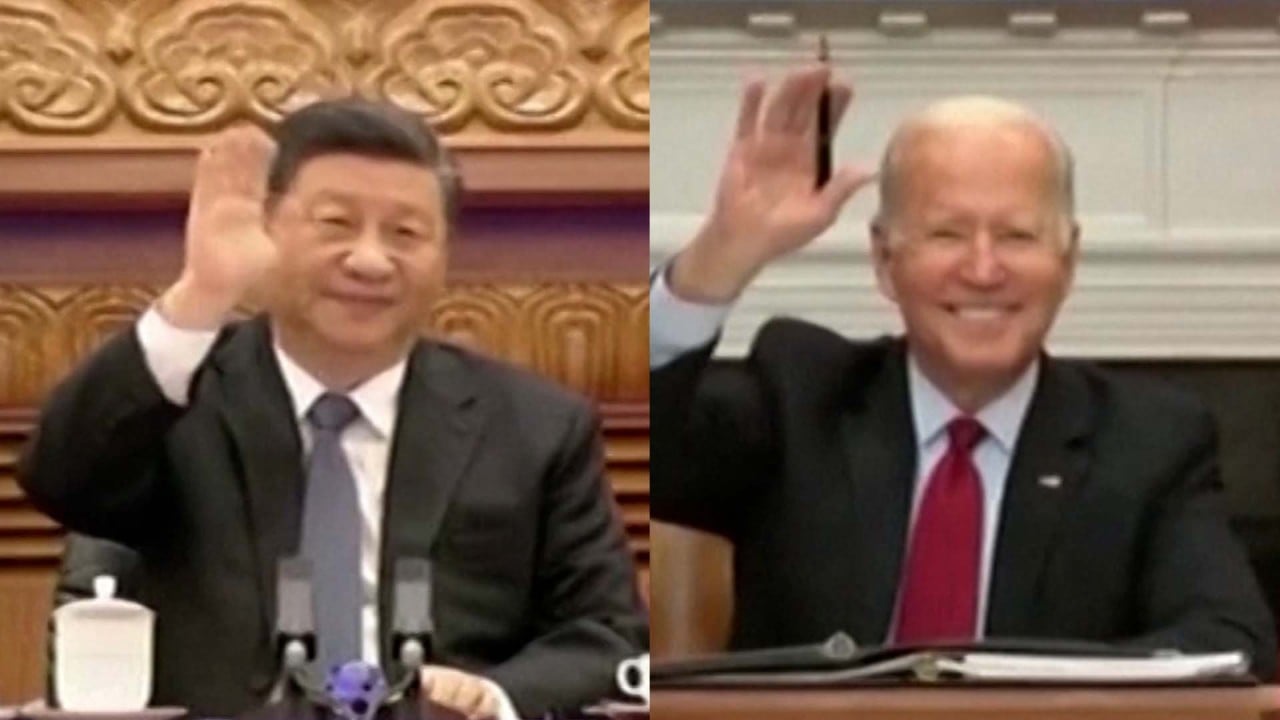

The summit’s unspoken bid to counter China comes weeks after Biden and Xi Jinping held a virtual summit that attempted to de-escalate tensions.

“China probably considers it an anti-China initiative,” Kurt Tong, former US consul general to Hong Kong and Macau, now a partner with the Asia Group, said on Tuesday.

“I think probably the stronger motivation for the United States is a reaffirmation to ourselves that we find those values important,” he added.

Others considered it unnecessary. “We don’t need the summit,” said Susan Thornton, a Yale University law fellow and former senior State Department official. “We have democracy, it’s good. We need to fix our problems, and we should spend our energy on that.”

Given those often glaring problems, the Biden administration has adopted a self-effacing stance, arguing that this is exactly the time to hold a summit in order to regroup.

“We know we’re not perfect – far from it – and we always have to strive to live up to our highest ideals and principles,” a senior administration official said on Tuesday. “We do intend to host this summit with humility.”