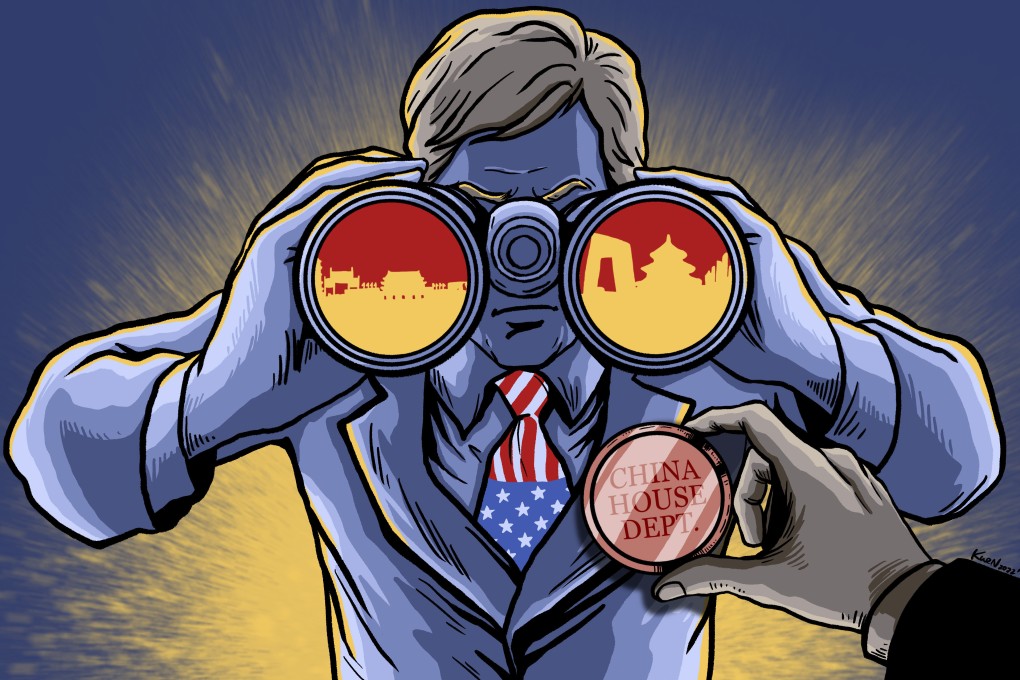

US plan to build ‘China house’ at State Department urgently needed but raises questions, analysts say

- Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s vision of expanded and dedicated cadre of China experts meant to implement policy across government departments

- While many former officials agree with initiative, some see hurdles to effectiveness in latest White House effort to focus resources on nation’s ‘most serious competitor’

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s plan to build a “China house” at the State Department addresses an urgent policy need for Washington, analysts and former diplomats said, but with more questions than answers about how the entity would operate and how much power it would wield, they are largely reserving judgment.

Blinken said the new team would inform Washington’s response to “the scale and the scope of the challenge” posed by China, describing the test for American diplomacy as “like nothing we’ve seen before”.

“I’m determined to give the State Department and our diplomats the tools that they need to meet this challenge head-on as part of my modernisation agenda,” Blinken said. “This includes building a China house: a departmentwide integrated team that will coordinate and implement our policy across issues and regions, working with Congress as needed.”

Since Blinken’s speech, no further details have emerged as to what shape the China cadre might take. According to a Foreign Policy report last September, the objective was to track “Beijing’s growing footprint in key countries around the world”.