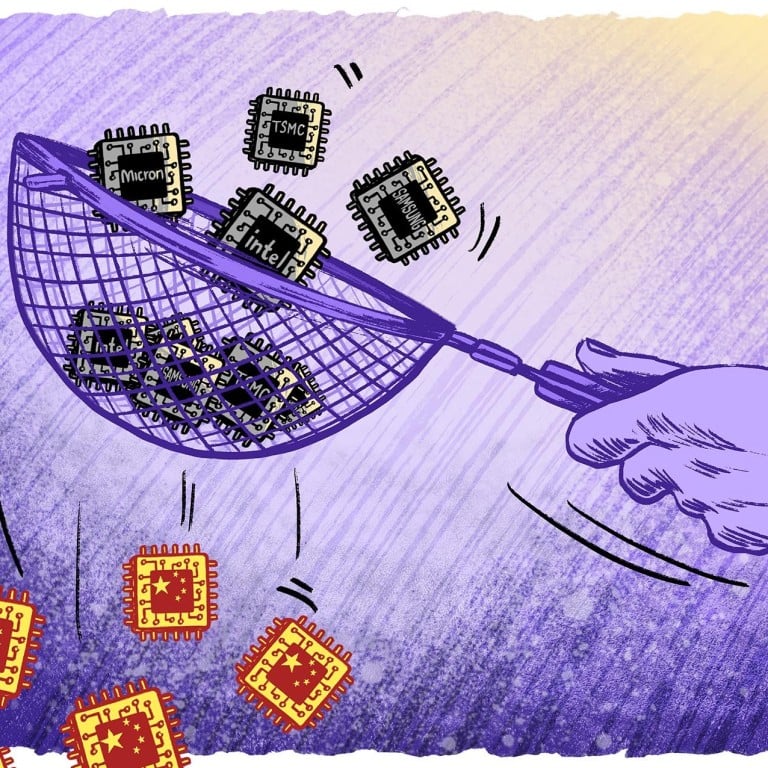

US and China both face tough struggles as war for chip supremacy intensifies following American export restrictions

- Washington imposes sweeping new rules targeting China but faces major challenges in bid to regain its global primacy in semiconductor manufacturing

- Asian rivals far outpace the US in making the advanced chips crucial for fighter jets, drones and cutting-edge military hardware

Restrictions announced last week on Chinese access to US semiconductor technology raise the stakes significantly in the US-China tech war, but Washington’s bid to regain chip manufacturing primacy and slow China’s military and economic rise faces huge challenges, industry analysts said.

The odds are long at best that the US chip industry can again dominate a field it pioneered, catch market leader Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) – which makes some 90 per cent of the world’s most advanced chips – or match Samsung Semiconductor Global any time soon.

“The short answer is no,” said Paul Triolo, senior vice-president with Albright Stonebridge Group and a former electrical engineer in Silicon Valley. “This is really complicated industry. It’s expensive and you’d better put your money where your mouth is.”

The United States is trying. In July, Congress passed the US$52.7 billion Chips and Science Act, which provides US$13.7 billion for R&D and US$39 billion for manufacturing subsides, although these amounts pale against those of foreign government’s or the capital spending of leading private competitors.

The breadth and scope of the latest moves intensify the US-China tech war and worsen the decline in bilateral relations. “Brace yourself,” said Xiaomeng Lu, geopolitical director at the Eurasia Group. “This is the next wave.”

While the US retains global leadership in some key areas, including chip-making tools and software, it is increasingly eclipsed by Asian rivals in manufacturing advanced chips crucial for fighter jets, drones and cutting-edge military hardware.

Intel, which all but invented semiconductors, has lost momentum, as US-made chip manufacturing declined to 12 per cent last year from 37 per cent in 1990, according to estimates by JPMorgan Chase.

Behind Taiwan and South Korea’s chip-making leadership are decades of relentless innovation, legions of talented engineers, long-time government support and an efficient supply chain, much of which the US lacks.

Tech war: Washington takes new steps to frustrate China, advance US chip-making

Chip makers also question the depth of America’s commitment, even as they grapple with restrictive US immigration policies and insufficient talent. Most tax breaks and funding under the chips and science law, for instance, last only a few years.

A more realistic US goal than lapping TSMC would see government funding jump-start US-based production enough that the country would not be crippled militarily or economically if the worst happened and mainland China invaded Taiwan. “The US has to pick its battles here carefully,” said Triolo.

In recent months, chip makers have announced massive new spending programmes, including US$100 billion for Micron and up to US$20 billion for IBM, both in New York; US$40 billion in Arizona and Ohio for Intel; US$17 billion in Texas for Samsung; and US$12 billion for TSMC in Arizona.

The chips bill – which took two years to become law – and Friday’s added rules also push the US further into the realm of industrial policy, which it has long condemned in China, Japan, South Korea and other countries.

“When Congress does something big and popular, it tends to go back to the well,” said Rory Murphy, vice-president of government affairs at the US-China Business Council. “In terms of industrial policy, this could be step one.”

Parcelling out funding under the new law, meanwhile, is expected to fall to an understaffed bureau of the Commerce Department making hugely consequential decisions with limited technical expertise, experts said.

Funding guidelines are expected in February, and analysts said it was unlikely any decisions have been made.

But of the US$39 billion going to manufacturing, they expect roughly US$20 billion to be divided among four major companies – TSMC, Intel, Samsung and Micron – another US$10 billion or so to a host of smaller chip, component and specialised players and the rest for makers of less advanced “legacy” chips used in autos and basic consumer products.

Elbowing has already started for a place at the trough. “Everyone’s firing up their lobbying,” said Lu.

Washington – and Arizona – dangle subsidies as US chip-making business returns

Analysts said Beijing has woken the sleeping giant with its chest thumping, outsize subsidies and explicit goal of global chip domination by 2049. As US resolve stiffens and its grip on advanced technology tightens, Beijing will likely step up its drive for technological self-sufficiency.

“It’s known for decades that its dependence on foreign semiconductor expertise poses a risk,” said Martijn Rasser, technology director at the Centre for a New American Security. “But this adds to the urgency.”

Growing US export restrictions will also hurt American companies that export billions of US dollars’ worth of technology hardware to China, undercutting their R&D funding, despite official US reassurance that the measures are carefully targeted.

Recipients of funding from Washington are barred from expanding high-end production in China for a decade. Chip maker Nvidia said in August, after the US banned its high-end chip sales to China, that its quarterly revenue could fall by US$400 million.

Tougher US sanctions are also likely to hurt major chip makers in Taiwan, South Korea, Japan and Europe that are under growing US pressure to reduce their hi-tech ties to China.

And the intensifying US-China tech war threatens to undercut global growth at a time when economies are already swooning. The value of global chip maker stocks have declined by over US$240 billion since Washington announced its restrictions.

“Despite very different tools and political-economic systems, both governments are increasingly emphasising ‘resilient’ economies and supply chains over economic efficiency,” said Michael Hirson, China research head with 22V Research and a former US financial attaché to China. “The clear loser here is the efficiency of the global trading system.”

But some argue that this is the price for safeguarding national security after decades of underestimating China’s outsize ambitions.

“Leaving it in the hands purely of international conglomerates and businesses is what led to the loss of supply chains and technology in the first place,” said Larry Wortzel, an American Foreign Policy Council fellow and former commissioner on the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Arizona courts more Taiwanese chip companies after TSMC investment

The US shares global leadership with Japan and the Netherlands in semiconductor-making equipment and software that China needs for its ambitious build-up. The fact that Washington went it alone last week with tougher measures rather than working with allies suggests differences over how hard to push Beijing, analysts said, although more coordinated policies could emerge later.

The US is also likely to find that the broader the export restrictions, the more leaky and difficult they are to enforce. The 2019 ban on chip exports to Huawei Technologies has been effective because it is narrowly focused and easy to track. Sanctions targeting entire Chinese industries and dozens of companies, however – on top of US export restrictions against Russia over its February 24 invasion of Ukraine – are much harder to prosecute effectively.

“China will figure out a way. You’re seeing it already,” said Lu. “And with the US opening battles on both fronts, Russia and China, it really needs to differentiate its goals.”

Bloomberg reported on Thursday that Shenzhen start-up Pengxinwei IC Manufacturing, founded by an ex-Huawei executive, has ordered US chip-making equipment for possible transfer to Huawei, in violation of a 2019 US ban. Huawei did not comment on the report, which cited unnamed sources.

Beijing’s response in coming weeks is likely to depend on how damaging it views the latest US restrictions for its tech industry and the Communist Party’s self-sufficiency goals. Last week, Beijing condemned the new export controls as an abuse of global trade principles designed to perpetuate US “technological hegemony”.

In response, Beijing could potentially add US companies to its unreliable entity list subject to sanctions; enforce new rules that subject foreign companies to lawsuits if they comply with “unjustified” foreign laws; or work to widen differences among the “Chip 4 alliance” – US, Japan, Taiwan and South Korea.

China also could restrict strategic exports, including lithium, at the heart of President Joe Biden’s bid to fight climate change and bolster electric vehicle usage.

Any Chinese bid to strengthen its tech self-sufficiency campaign must grapple with disappointing results.

Analysts estimate that China can meet perhaps 25 to 40 per cent of its domestic demand with locally designed semiconductors by 2025, more than double current levels. But that remains well below its own 70 per cent by 2025 ambition.

US-China tech war weighs on Xi Jinping’s legacy ahead of 20th party congress

China has repeatedly defied expectations and dominated new industries. But semiconductors are a tougher challenge, particularly if the US-led effort to deny advanced Western technology succeeds.

Semiconductor innovation is built on sharing cutting-edge expertise across a global supply chain that China will find difficult to re-create alone. And unlike other industries it has disrupted, China faces multiple world-class competitors with decades of hard-fought experience.

In addition to TSMC’s lock on the world’s most advanced microprocessors, the Netherlands’ ASML dominates ultraviolet lithography essential in making cutting-edge circuits. Two South Korean giants dominate the memory chip market. And three US-based firms control most of the semiconductor software market.

China’s top anti-corruption body probes ex-semiconductor fund executive

While China has poured over US$100 billion to fuel its chips ambition, questions over efficacy and waste abound. In recent weeks, investment output and morale at Beijing’s US$39 billion state-run semiconductor “Big Fund” have plunged after several top executives were arrested for suspected corruption.

But Beijing likely views this as the necessary cost of its longer-term goals, Lu said, in much the same way the Communist Party has waged a near continuous anti-corruption campaign since President Xi Jinping took power in 2012.

“In the short term, it will take down some people,” said Lu. “But it’s a cleansing move that makes the system more effective, that’s their logic.”