Joe Biden’s US summit with Japanese, South Korean leaders looks to send ‘unity’ message

- Meeting at Camp David is expected to result in a series of defence, economic and diplomatic agreements aimed at pushing back against China

- ‘Strengthening our trilateral cooperation is critical to delivering for our people, for the region and for the world,’ says US Secretary of State Antony Blinken

For years, Beijing has counted on the historic animosity between Japan and South Korea as part of its divide and conquer playbook, even as Washington has worked to bolster its alliances and counter China’s growing footprint. At this week’s summit between the leaders of Japan, South Korea and the United States, Washington is hoping to permanently blunt with a show of unity that Chinese advantage on the geopolitical chessboard.

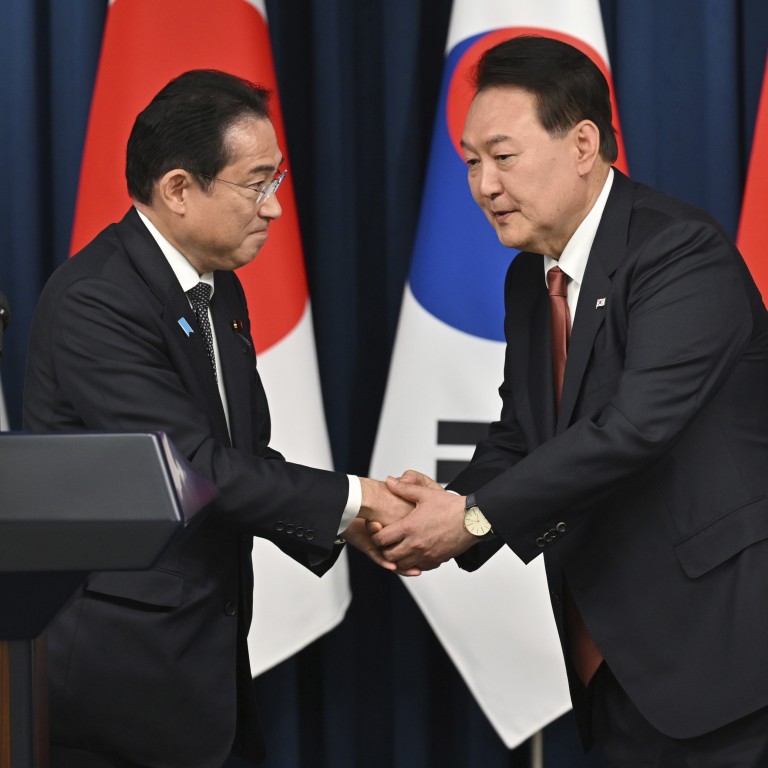

On Friday, US President Joe Biden, Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol will convene at the Camp David presidential retreat in Maryland for talks to strengthen ties, project a united front and announce a series of defence, economic and diplomatic agreements aimed at pushing back against the Asian giant.

“China, they will certainly not say anything positive and will be very critical of the trilateral statement,” said Christopher Johnstone, a senior fellow at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) and a former CIA analyst. “They have always seen the difficulties between South Korea and Japan as a freebie for them, one where they wouldn’t have to work very hard to split the allies.

“Now that that has been repaired, the Chinese see very little advantage.”

While the three leaders have met five times on the margin of multilateral events, this is their first stand-alone summit and Biden’s first Camp David hosting of such an event.

Among the potential “deliverables” the leaders could announce on Friday are a collective security agreement that falls short of Nato’s ironclad Article 5 guarantee; annual joint military exercises; a new hotline; regular military dialogues; more cooperation on supply chains and emerging technologies; enhanced people-to-people exchanges; and a pledge to hold a trilateral summit annually.

“Strengthening our trilateral cooperation is critical to delivering for our people, for the region and for the world,” US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said on Tuesday after meeting his Japanese and South Korean counterparts.

Can Japan and South Korea seal ‘historic’ security alliance at US summit?

“I don’t know that this trilateral will derail that,” said Sheila Smith, a senior fellow with the Council on Foreign Relations. “It’s not necessarily a tit for tat. But it’s certainly an avenue that the Chinese are pursuing.”

Another possible Chinese response – playing tough with Seoul and Tokyo to show their displeasure – may be unpalatable given China’s swooning economy and need for foreign investment.

Although Biden is hosting the summit, analysts credit Yoon with building the momentum.

Although the three leaders are not expected to criticise Beijing directly, analysts see the trilateral as a direct response to shared external concerns. These include China’s naval, missile and nuclear build-up; North Korea’s increasingly capable intercontinental ballistic missile programme; and Russia’s attack on its smaller neighbour, which resonates in Asia.

“China is definitely present in the minds of all three leaders, even if the communique does not underscore it,” said Scott Snyder, a senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.

The summit is likely to reinforce entrenched narratives. The US sees its allies and partners strategy as a necessary counter to an increasingly aggressive China bent on undermining global rules, playing coercive economic bully and flexing its military muscling in the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait.

China sees its attempts to counter Western alliances and engage unilaterally as essential to counter a US-led encirclement strategy meant to isolate China, undercut its ability to develop, meddle over Taiwan and spread US values to effect regime change in Beijing and Moscow.

China opposes UN Security Council meeting on North Korea rights

“They see themselves as having less leeway and less room when the three allies are together,” said Victor Cha, the Korea chair at CSIS who was with the US National Security Council from 2004 to 2007. “They can exercise a lot more leverage when they deal with them bilaterally.”

Even as the three nations project an image of unity against authoritarianism this week, national interests and tensions inevitably create seams between the allies.

“There’s a little risk of overhyping,” said Tobias Harris, Indo-Pacific deputy director at the German Marshall Fund of the United States. “There are real limits.”

Washington’s inordinate focus on regional military security leaves many Asian partners eager for it to do more on trade and economics and counter China’s dominant position.

This follows disappointment with Washington’s 2017 departure from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement and failure to join its successor, the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership. The US offering, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, lacks significant market access provisions or a congressional mandate.

Japan “will continue to convey the message to Washington that the US return to the CPTPP is crucial,” said Yuko Nakano, a CSIS Japan fellow. “Such a return would signal the depth of US engagement in the Indo-Pacific.”

And even as South Korean and Japanese companies invest billions of US dollars in semiconductors and electric vehicles central to Biden’s clean energy and export control policies, they are concerned that US firms are being subsidised at the expense of their own.

Another question is how durable the trilateral alliance is amid concerns over political backsliding, whether between Japan and South Korea given their long-held sensitivities, or in Washington and its commitment to global engagement if a Republican is elected president next year.

“At the end of the day, there’s little you can do to prevent future political leader from walking away,” said Johnstone, a former State Department official. “But the more that the three countries can do to regularise, formalise, institutionalise the cooperation that they’re building, the more difficult it becomes.”