Advertisement

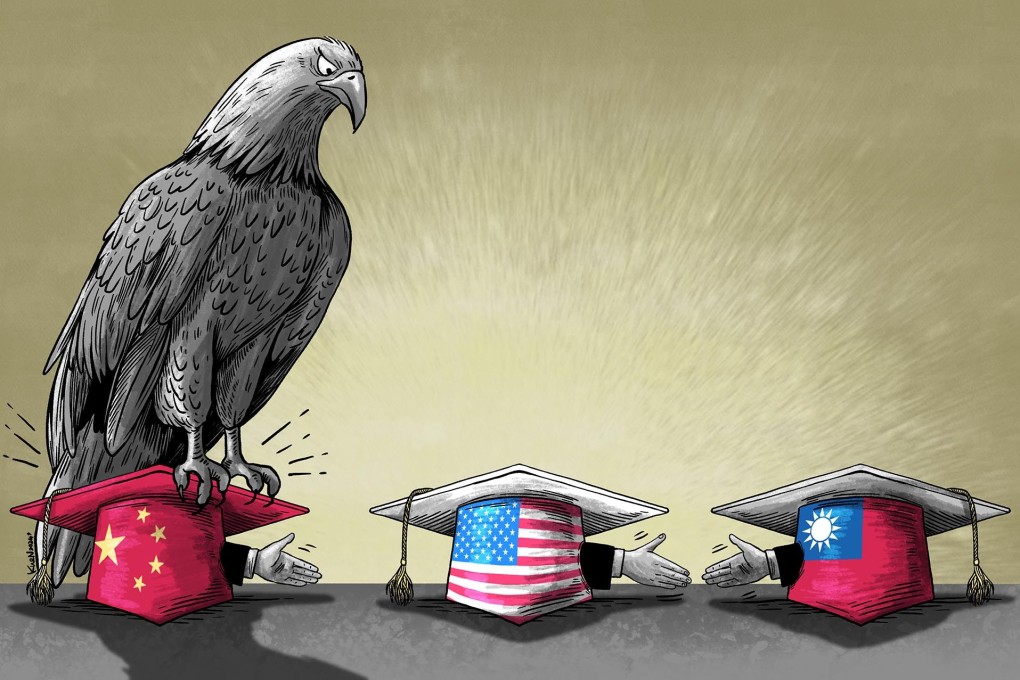

Anti-Beijing policies in US hasten an academic switch to Taiwan

- Many US universities, including Harvard, are strengthening ties with mainland China, but anxiety about Beijing’s influence has made Taiwan partnerships more attractive

- China experts maintain, though, that programmes on both mainland China and Taiwan have their own distinct value

7-MIN READ7-MIN

70

A victim of US state laws targeting Sino-American academic collaboration has found a new home: Taiwan.

In February, after terminating a two-decade partnership with the Tianjin University of Commerce and several other partnerships with mainland Chinese schools, Florida International University finalised a memorandum of understanding with Shih Chien University in Taipei.

FIU, a Miami-based public university known for its international ties, has said that the phase-outs were triggered by new foreign influence legislation in Florida, which require public schools to get the approval of a skeptical state government to maintain partnerships with China.

Advertisement

Florida International isn’t the first school to opt for Taiwan over mainland China. In 2021, Harvard University made national headlines when it chose to move its popular summer Mandarin-language course from Beijing to Taipei – a decision many regarded as a reflection of the souring US-China relationship.

But while private schools like Harvard have not seen an overall reorientation away from mainland China and Beijing is eagerly trying to welcome 50,000 young Americans to China in the next five years, political winds increasingly favour Taiwan.

The US and Taiwan have long been close education partners; however, anxiety about China’s influence and enthusiasm about Taiwan’s changing geopolitical role have created a flood of new and expanded initiatives between the two sides – initiatives that some China experts warn cannot truly replace engagement with the mainland.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x