Advertisement

Born in China, raised in US: adoptees explore the meaning of identity at Lunar New Year

Growing up Chinese-American has not been easy for LuLu Grant and Phoebe McChesney, both wanting to fit in, while never too far from the past

Reading Time:6 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

2

Lucy Quagginin New York

Lunar New Year wasn’t always on LuLu Grant’s radar. Adopted at two from Fuzhou, China and raised in the US state of Washington, Grant decided to cut her birth country out of her life at a young age. Decades later, she would celebrate Spring Festival alongside her birth family with a complex array of feelings about her two worlds.

“People think that finding your birth family is so joyous, and part of it is, but it’s also very sad and very difficult,” she said, adding that “it’s not how I wish it were, and sadly, it’s never going to be that. That’s impossible.”

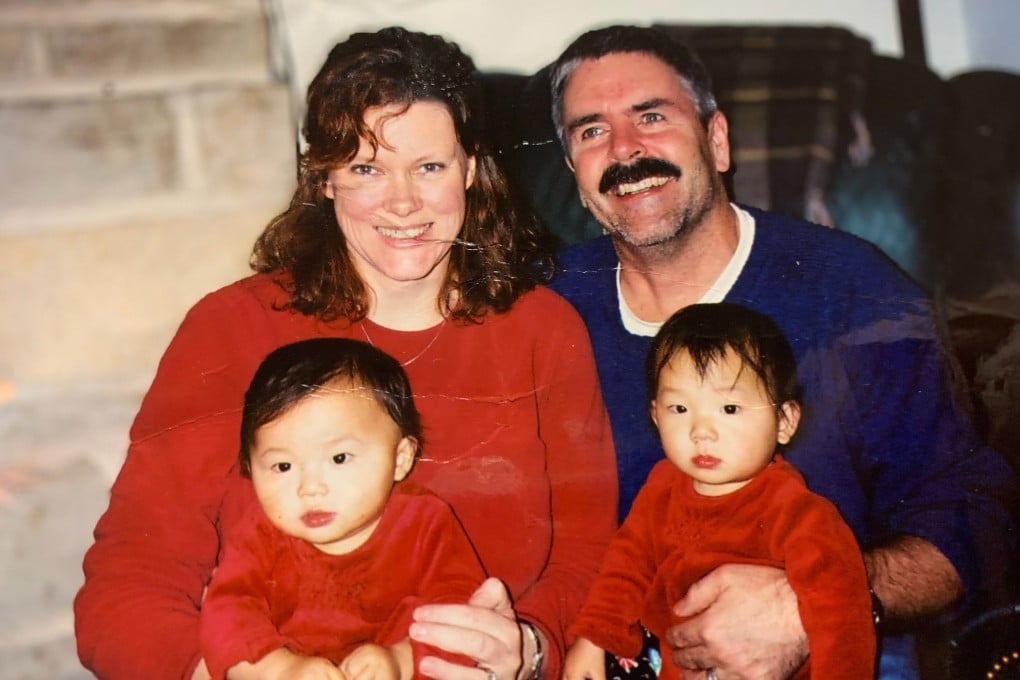

Growing up in Illinois, Phoebe McChesney’s parents tried to incorporate Chinese culture into their lives after adopting her and her twin sister from Hunan, China.

Advertisement

Her family would often celebrate Lunar New Year, with her father cooking well-meaning but sometimes questionable Cantonese food. It was his effort to connect with Chinese culture, she said, despite her heritage being Hunanese, a region with very different cuisine.

The Lunar New Year is a time for Chinese people to come together to celebrate family. Yet for some adoptees like Grant and McChesney, it can bring up complicated feelings about their heritage and birth families. These children, now adults, are examining their identities through the lens of their past, as they search for answers about both what it means to be Chinese and what it means to be American.

Advertisement

China’s international adoption programme began in 1992, during the country’s one-child policy era, which began in 1980 to curb population growth. China today has one of the lowest birth rates in the world. Its shrinking population led to the end of the one-child policy in 2015. These factors are assumed to be why China ended its adoption programme in 2024.

According to non-profit organisation China’s Children International, many families resorted to giving up their children due to the “societal importance of males within China’s traditional familial structure and compounded by the economic pressures faced by many families in rural areas”.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x