Little chance of thaw in Sino-Japanese ties at G20 summit

Continuing a series of stories on China’s relations with other G20 members ahead of next month’s G20 summit, the South China Morning Post looks at the strained relationship between President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe

When China hosts the summit meeting of the Group of 20 leading nations and economies in Hangzhou in September, the interaction – or lack of it – between President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe will be closely watched.

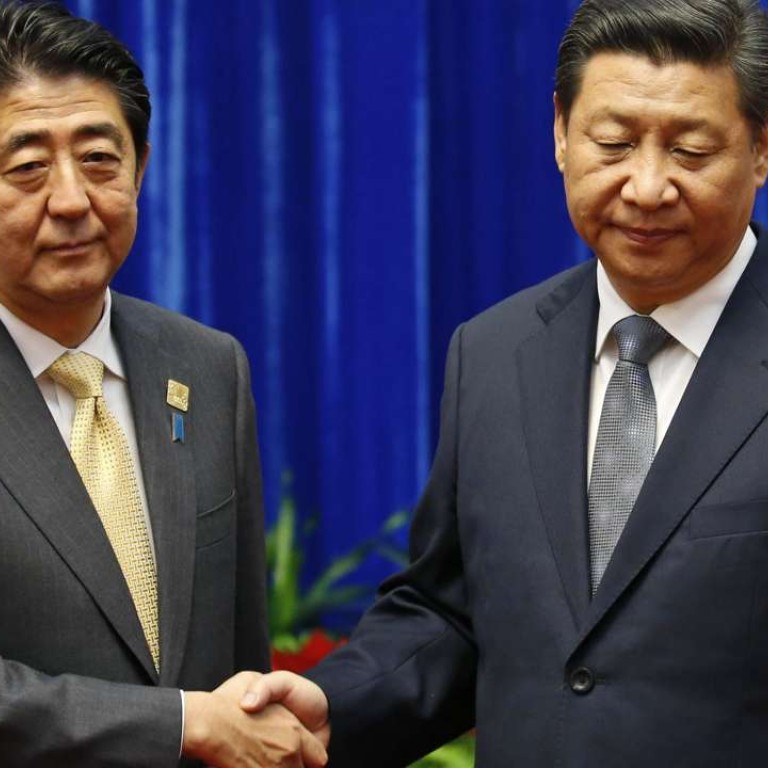

Both nations have been carefully assessing the state of bilateral ties and calculating whether the two leaders should meet on the sidelines of the G20 summit, as they did at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit in Beijing two years ago. That occasion was marked by a frosty handshake, followed by a vow to remove obstacles impeding Sino-Japanese ties.

China does not have a very strong momentum to engage in serious talks with Japan

As host, it is almost diplomatic protocol for Xi to meet with leaders attending the event, and especially so in the case of the leader of Japan, one of China’s key neighbours. Both sides are also aware that such talks are essential if they hope to contain confrontations over territorial and historical disputes. However, it is also unlikely the two leaders would reach a consensus on anything and there’s always the risk a meeting could end up with each side blaming the other for recent tensions.

“China does not have a very strong momentum to engage in serious talks with Japan,” said Zhou Yongsheng, a Japanese affairs expert at China Foreign Affairs University. “For Beijing, the development of Sino-Japanese ties over the past two years shows that things could easily turn sour regardless of what agreements have been made in previous talks.”

The Sino-Japanese relationship has gone through rocky patches since they normalised ties in 1972, mainly over grievances dating back to the second world war and a territorial dispute over the Diaoyu Islands in the East China Sea, which Japan controls and calls the Senkakus.

But the relationship deteriorated markedly in 2012, when Japan announced it would purchase three of the disputed islands from a private landowner, triggering massive anti-Japanese protests in China. Since then, both nations have sent more vessels to waters around the disputed islands and conducted more naval drills. On one occasion they accused each other of locking onto their vessels with fire-control radar, raising fears of a major military conflict.

Making matters worse, Beijing branded Abe an “unwelcome person” after his December 2013 visit to the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo that honours Japan’s war dead – including 14 Class A war criminals from the second world war. That made the chances of an improvement in bilateral ties even slimmer.

But neither side could afford a sharp escalation in tensions, given that annual bilateral trade is now worth more than US$300 billion, and the two leaders finally met in November 2014 on the sidelines of the Apec summit.

Xi and Abe shook hands awkwardly before their talks, with Xi appearing to scowl and avoiding eye contact in front of the cameras. However, the two leaders still managed to uphold a four-point consensus reached by their diplomats before the talks, which included both acknowledging that they had “different positions” over the territorial dispute and committing to overcoming “political obstacles” in bilateral relations in the spirit of “facing history squarely and looking forward to the future”.

Xi and Abe also met on the sidelines of the Asian-African summit in Jakarta in April last year, maintaining the momentum towards a more stable relationship. But things started to spiral downwards again in recent months, which will overshadow the two leaders’ interactions in Hangzhou.

“Compared with the situation in 2012, when the Japanese government purchased the Senkakus, the current relationship is better, but worse than in 2014,” said Hiroko Maeda, a non-resident fellow at the Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA in Washington.

“Xi will make the decision if he meets Abe by considering the degree of the tension with Japan, the actual condition of US-Japan-South Korea cooperation, and the situation in the South China Sea just before G20.”

Citing concerns about freedom of navigation, Tokyo’s criticism of China has recently extended beyond the East China Sea and into the South China Sea, where China is engaged in bitter territorial disputes with its Southeast Asian neighbours.

Beijing has called on Tokyo to desist from becoming involved in the South China Sea disputes. A stern-looking Foreign Minister Wang Yi told his Japanese counterpart Fumio Kishida in early May that Japan “should know the reason behind” the setback in the Sino-Japanese relationship and should respect China’s interests.

Wang’s warning was not well received in Japan. At a G7 meeting in Ise-Shima later that month, the bloc agreed to send a strong message on maritime claims in the South China Sea. China said it was “extremely dissatisfied” with Japan and the G7.

Diplomatic relations between the two nations got more complicated following a ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague in July that rejected China’s historic claims to the South China Sea. The United States and Japan called on parties involved in the dispute to follow international law after the ruling in the case, which was initiated by the Philippines.

Bhubhindar Singh, an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, said the tensions in the South and East China seas would definitely influence the atmosphere at any meeting between Xi and Abe, with two leaders appearing to have won domestic support for get-tough stances towards each other.

“I think President Xi would again have to express China’s opposition towards Japan’s position,” Singh said. “He’s probably again going to appear very strong in support of China’s stance.

“I think they will probably meet on the sidelines, but I don’t think any improvement is expected.”

Tensions would be a constant feature of Sino-Japanese relations as long as Xi and Abe were in power, but both leaders realised that war or even a short conflict would be “extremely detrimental”, he added.

“I think both countries are going to stress the importance of maintaining some communication in order to ensure the tensions will not deteriorate further,” he said.

Shi Yinhong, an international affairs professor at Renmin University, said for at least six months before the Xi-Abe meeting two years ago, both nations had put tremendous efforts into making the talks happen. However, there was no such effort to push for Sino-Japanese talks at the G20 summit next month.

He said that in the lead-up to the G20 summit in Hangzhou “nothing has been done to pave the way for serious talks between the two sides”.

“Things have turned bad,” Shi said.

Before the 2014 talks, Japan’s most senior China hands, including former prime minister Yasuo Fukuda and former foreign ministers Masahiko Komura and Katsuya Okada, visited China for meetings with Chinese officials. Abe’s national security adviser, Shotaro Yachi, also visited China.

Officials and diplomats from the two nations did meet early this month, but only to lodge protests and engage in heated exchanges. On August 9, Kishida said Sino-Japanese ties had worsened “markedly” when summoning Beijing’s envoy to Tokyo, Cheng Yonghua, to protest about China sending more than 200 vessels, some of them armed, to the East China Sea. Cheng said the islands were part of China’s territory and it was normal for Chinese vessels to conduct activities there.

The Japanese government hopes Xi and Abe can meet during the G20 summit to discuss China’s maritime activities, Kyodo News Agency reported, citing Japanese government sources.

Observers expect some interactions between Xi and Abe in Hangzhou next month and say bilateral talks are possible, even though they would be largely symbolic.

“Even if such a meeting was held, it would be made possible merely for courtesy,” said Li Mingjiang, an associate professor at the S. Rajaratnam school of international studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. “There are not many concrete things that they can talk about and agree about.”

Sino-Japanese ties flourished in the 1980s, partly because of Japan’s involvement in China’s economic modernisation. But the trend has reversed since the 2000s, when China’s economic power began to rise, and especially after China replaced Japan as the world’s second-biggest economy in 2010.

In September of that year, a Chinese fishing trawler collided with two Japanese coastguard vessels near the Diaoyus, and the trawler’s captain, Zhan Qixiong, was arrested.

Then, in 2011, China denounced a Japanese defence white paper for spreading the “China threat” theory.

Mistrust between the two countries has continued to deepen since then, with Tokyo concerned China is using its economic power to boost its military capabilities and gain diplomatic influence with a view to stymieing Japan’s foreign policy goals. Tokyo has also refused to join the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, citing concerns over a lack of transparency.

Beijing, meanwhile, is worried about Abe’s move to amend the Japanese constitution to expand the role of the military and sees Japan teaming up with the US to exert pressure on China on a range of regional issues.

“Japanese don’t think that China wants a real war with Japan, but see that China continues to pose physical pressure,” Maeda said.

Observers said tensions between China and Japan were likely to linger, with the ruling Liberal Democratic Party-led coalition’s victory in July’s upper house election in Japan a reflection of voters’ concern about China and support for Abe’s foreign policy.

“Confrontation between China and Japan has become a new normal,” said Da Zhigang, director of the Institute of Northeast Asian Studies at Heilongjiang Academy of Social Sciences. “The policy of getting tough towards China is gaining popularity in Japan.”

While the two sides will continue to seek cooperation in economic matters and trade, disaster relief and cultural exchanges, mistrust could deepen further if they step up tough rhetoric and actions.

“Engagement and hedging is Japan’s basic China strategy,” Maeda said. “However, as China escalates its actions in surrounding areas, Japan weighs more to hedging.”

Timeline of modern Sino-Japanese relations

1945 – Japan renounces its territorial claims in China after the end of the second world war

1949 – Japan does not recognise the People’s Republic of China following the end of the civil war, maintaining diplomatic ties with the Nationalist government that fled to Taiwan

1972 – Japanese Prime Minister Kakuei Tanaka visits China and diplomatic relations between the two countries are normalised

1978 – Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping visits Japan and a Treaty of Peace and Friendship is signed

1979 – Japanese Prime Minister Masayoshi Ohira pledges first government-to-government yen loan to China during visit

1982 – Premier Zhao Ziyang visits Japan and proposes the “three principles of Sino-Japanese relations”

1984 – The 21st Century Committee for Sino-Japan Friendship holds its first meeting

1985 – Japanese Prime Minister Yasuhiro Nakasone visits the Yasukuni Shrine, angering China

1989 – Japan adopts sanctions against China after the Tiananmen Square crackdown

1991 – Japanese Prime Minister Toshiki Kaifu becomes the first G7 leader to visit China since the Tiananmen Square crackdown

1992 – Communist Party general secretary Jiang Zemin visits Japan to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the normalisation of diplomatic relations

Emperor Akihito makes first Japanese imperial visit to China

1993 – Japanese Prime Minister Morihiro Hosokawa offers apology for Japan’s wartime aggression in speech to Japanese parliament

1995 – President Jiang Zemin visits Japan.

Japan cuts grant aid in response to China’s nuclear tests

1999 – Japanese Prime Minister Keizo Obuchi visits China and agrees to its accession to the World Trade Organisation

2001 – Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi makes the first of six annual visits to the Yasukuni Shrine, angering Beijing

The two countries impose tariffs on each other’s imports

2003 – Poison gas shell discarded by the Japanese army during the second world war injures dozens of people in Qiqihar, Heilongjiang province

2007 – Wen Jiabao becomes the first Chinese premier to address Japanese parliament

2005 – New edition of Japanese history textbook prompts protests from China and South Korea Japanese oil company receives government permission to exploit natural gas resources in the disputed areas in the East China Sea, angering Beijing

China opposes Japan’s bid for a permanent seat on UN Security Council.

2008 – President Hu Jintao calls for increased cooperation during the first visit to Japan by a Chinese head of state in more than a decade

2012 – Japan purchases three of the Diaoyu Islands, known as the Senkakus in Japan, causing further deterioration of bilateral diplomatic relations

2013 – Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visits Yasukuni Shrine