Response to Pyongyang rockets signals end of South Korean leader’s China honeymoon

In the sixth story in a series on China’s relations with other G20 members ahead of next month’s summit in Hangzhou, the South China Morning Post examines the factors that led to a cooling of Beijing’s ties with Seoul

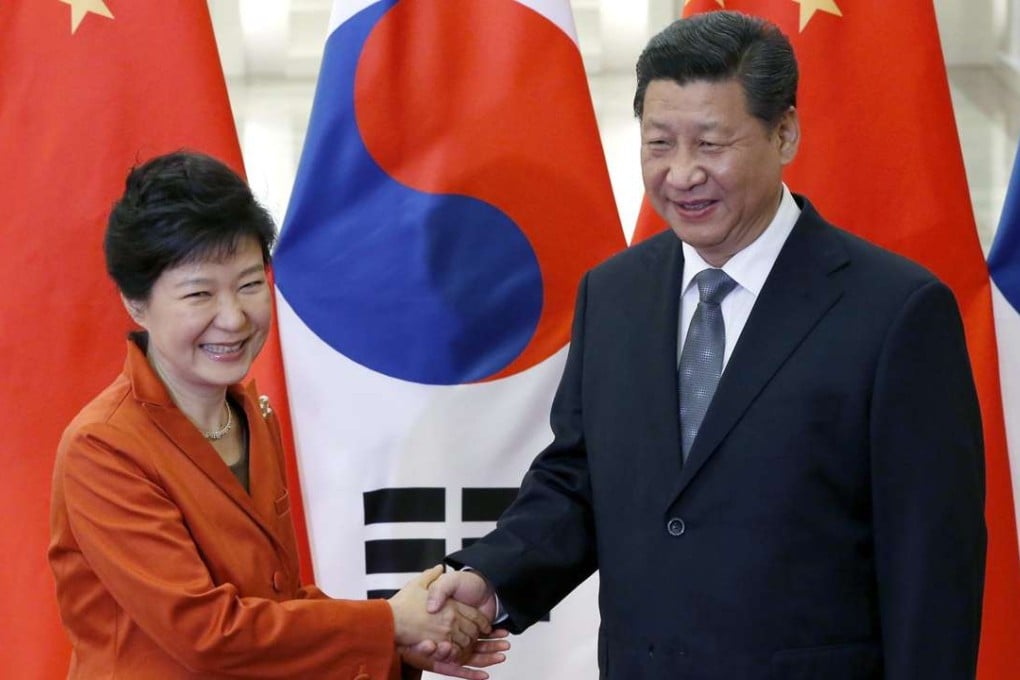

When Beijing hosted the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum summit in the autumn of 2014, President Xi Jinping told his South Korean counterpart Park Geun-hye on the sidelines of the meeting that the two nations were “good neighbours and good partners that live next to each other and walk shoulder to shoulder”.

The broad smiles on the faces of the two leaders were quickly captured in photos that were highlighted by Chinese and South Korean media as a symbol of the best period in bilateral relations between Beijing and Seoul.

When Park found that China failed to keep a rein on Pyongyang, unrealistic hopes were broken

However, the smiles may not be as broad next month, when Xi hosts world leaders at the G20 summit in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province.

The turning point came in early July, when Park, the Putonghua-speaking South Korean president whom Xi described as “an old friend of the Chinese people”, agreed to the deployment of a powerful US anti-missile system on Korean soil.

To Beijing, Park’s decision marks a severe setback for China’s foreign policy efforts on the Korean Peninsula after years of attempts to draw South Korea away from its long-time ally, the US, and exert leverage on Japan, another firm ally of the US.