As Suu Kyi heads home, solving dam deadlock remains key to improving ties between China and Myanmar

Experts say domestic opposition means Myanmarese government is unlikely to bow to pressure from Beijing

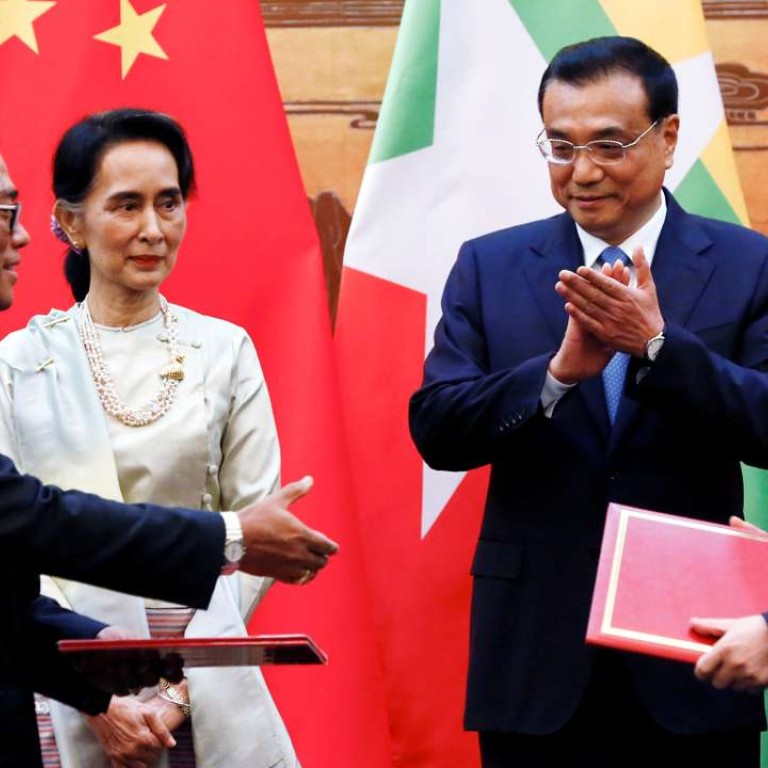

The improvement of ties between China and Myanmar still hinges on a deadlocked dam project despite Aung San Suu Kyi’s largely successful visit to China as Myanmar’s de facto leader, according to diplomatic observers.

The suspension of the US$3.6 billion Myitsone project on the Irrawaddy River by Suu Kyi’s predecessor Thein Sein in 2011 plunged the otherwise friendly relations between Myanmar and China, its top trading partner and investor, to an all-time low that coincided with the start of Myanmar’s democratic tilt towards the West five years ago.

[China] may be willing to compromise on this issue in return for progress on its real priorities

Although her Chinese hosts agreed to further economic cooperation and increased investment on infrastructure projects in Myanmar despite lingering disputes over the Myitsone dam, experts say there is a long way to go before any breakthroughs in mending damaged ties.

Along with cementing China’s support for Myanmar’s ethnic reconciliation process, the dam project topped the agenda for Suu Kyi’s five-day visit, which ended on Sunday.

At her request, President Xi Jinping reiterated his support for Myanmar’s challenging peace process and promised to help bring warring ethnic groups, especially those on China’s southwestern border with Myanmar, to key talks scheduled for later this month.

But both sides appear to have made little headway on the contentious Myitsone dam.

Du Jifeng, a Southeast Asian affairs expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said that considering simmering anti-Chinese sentiment in Myanmar, it was most unlikely that Suu Kyi would make substantial concessions on the project despite mounting Chinese pressure.

Both Xi and Premier Li Keqiang urged the Myanmarese authorities to settle disputes over the dam project properly to avoid possible further damage to the bilateral ties.

In response, Suu Kyi promised to find a resolution that “suits both sides’ interests” but refused to give a detailed timetable.

Less than a week before her visit to China, Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy (NLD) government established a new commission to evaluate the suspended Myitsone dam and other controversial hydropower projects.

Experts said the commission’s first report was not expected until mid-November, while a full study of the dam’s potential effects could take three to four years to complete.

While Beijing saw the suspension of the biggest Chinese-invested project in Myanmar as a major setback in diplomatic relations with an otherwise friendly political ally, it has largely been popular in Myanmar, helping to allay growing public anger over Myanmar’s economic dependence on China and woo the West and Myanmar’s Southeast Asian neighbours.

The Myitsone dam project, part of a hydropower development deal including a further six mega dams on the Irrawaddy and its tributaries, was initiated in 2005 between Myanmar’s then junta chief, Than Shwe, and former president Hu Jintao.

At a cost of US$20 billion and with a total capacity of 20,000 megawatts, the dams, to have been built by China Power Investment Corporation, were seen as a symbol of China’s growing regional influence. Mainland media dubbed them China’s overseas Three Gorges Dam project.

But the Myitsone dam, in the ethnic Kachin region near Myanmar’s northern border with China, has long been a magnet for criticism, protests and even violent opposition by local people and green groups.

Apart from concerns about potential ecological destruction on the Irrawaddy and the resettlement of 10,000 people, locals were aggrieved that 90 per cent of the electricity generated by the dam was supposed to go to power-hungry China.

Instead of resuming construction of the dam, most experts tend to believe both sides are working on alternatives to the original plan.

Thant Myint-U, a Myanmarese historian and the author of Where China Meets India: Burma and the New Crossroads of Asia, said the Myitsone dam was not really China’s main interest in the country.

“[China] may be willing to compromise on this issue in return for progress on its real priorities, like the planned deep sea port on the Indian Ocean and, even more importantly, a stronger bilateral relationship than Myanmar has with any Western country,” he said.

David Steinberg, a Myanmar expert at Georgetown University in Washington, said Suu Kyi could not afford to risk losing domestic support by bowing to pressure from Beijing. He suggested she might agree to the building of other dams in a bid to mitigate that pressure.

His views were echoed by reports in Myanmar’s media suggesting secret bilateral negotiations may have been under way to find alternative dam sites to avoid similar embarrassment for both governments.

Experts said it was too early to tell if suitable alternative sites could be found, but it would be a face-saving way out for Beijing and Suu Kyi’s government, caught between China’s economic clout and domestic opposition to the Myitsone project.

Jonathan Chow, a Myanmar expert at the University of Macau, said that if China wanted to send a strong signal of its commitment to positive long-term bilateral relations, it could hardly do better than agreeing to cancel the Myitsone dam.

“Compensation for the terminated contract would need to be worked out, but the Myitsone dam has become a potent symbol of the negative effects of China’s economic presence in Myanmar,” he said.

Chow warned the Myitsone dam was likely to stoke further anger against China and Suu Kyi and could be interpreted in some circles as a sign that political reforms in Myanmar were going into reverse.

“Removing the Myitsone dam from the picture would be a dramatic symbol of improving bilateral relations, boost the standing of both the NLD and China in Myanmar, and make it more politically feasible to pursue other, more sustainable joint infrastructure projects,” he said.

Du said the stakes over the Myitsone dam project were so high that they might have adversary impact on other major energy cooperation projects, such as oil and gas pipelines between Myanmar and Yunnan province, and further damage bilateral ties.

“It is highly unlikely that the Myitsone dam can be resumed, but it is also unrealistic to expect a mutually acceptable alternative solution any time soon,” he said.

Additional reporting by Laura Zhou