Opinion | China’s border row with India points to mutual distrust – economic and trade ties notwithstanding

Mohan Guruswamy writes that India’s absence from the Belt and Road summit in Beijing was seen as evidence of strained relations between China and India

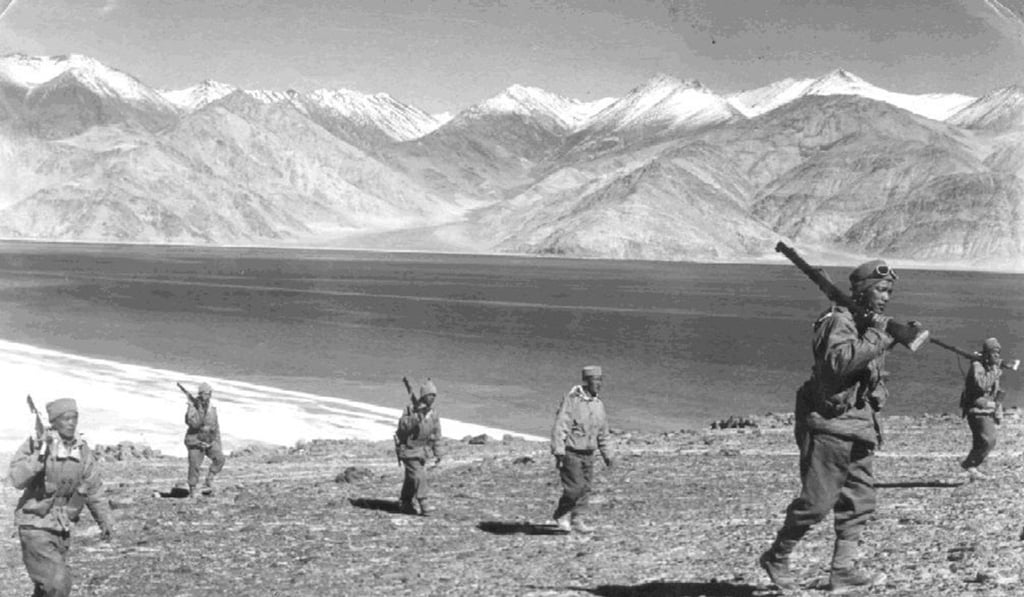

The Sino-Indian border is 4,056 km long, and for the most part it straddles the Himalayan crest and goes over desolate areas. Not a shot has been fired across the border since 1967, when the armies of China and India fought a short but brutal war at Nathula, very near the area of the present standoff.

Both countries have large concentrations of troops, often eyeball to eyeball, all along the border. The problem is that not only is the border not demarcated, even the lines of actual control are not defined. This leads to overlaps, and troops on patrol often accost each other. The two countries have a set of agreements and local arrangements to prevent conflict. One of the key agreements is not to disturb the status quo and not build anything that will affect the tactical situation. But why did the latest military standoff take place? Both sides have resorted to the blame game, accusing each other of breaching the commitments.

Many questions occur. But what has really happened at Dokalam and Doka La? Is it a coincidence that it occurred just days ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s summit meeting with Donald Trump? Or is it a consequence of India not taking part in the conference on Beijing’s “Belt and Road Initiative” organized by China? Many theories abound, but the fact is few outside both governments actually know what led to the present impasse. The Indian public believes it is China that is ratcheting up the tensions. The Chinese public thinks it is India. In the new world of mass and instant communication, perceptions are the truth.

However, some light is peeping out from under the shut doors of the two militaries. At the farthest tip of the Chumbi Valley, between Sikkim and Bhutan, the Chinese are building a road to an area called the Dokalam Plains. This area is claimed by both China and Bhutan. Tibetan and Bhutanese yak and graziers use it. With a road built, the Indian Army believes that artillery can be positioned at Dokalam and will seriously threaten India at its very strategic and sensitive passage to northeastern India. This sliver of territory is commonly known as “Chicken’s Neck” in India. It doesn’t help very much that the Chumbi Valley too appears on the map like a dagger poised not only to render asunder Sikkim and Bhutan, but also Assam and the Northeast from the rest of India.

Strictly speaking, it can be argued that this latest dispute is one between China and Bhutan. Bhutan became a protectorate of British India in 1910, after signing a treaty allowing the British to “guide” its foreign affairs and defence. Bhutan was one of the first to recognise India’s independence in 1947 and both nations fostered close relations, their importance augmented by the annexation of Tibet by China in 1950. China has border disputes with both Bhutan and India. Since August 1949, Bhutan and India have had a Treaty of Friendship, wherein Bhutan agreed to let India “guide” its foreign policy and both nations would consult each other closely on foreign and defence affairs.