South China Sea forecast a year after court ruling: calm but waves expected

Philippine president’s pivot to Beijing has changed game but tensions linger among seven claimants

A year of relative calm in the South China Sea following a historic ruling against China’s territorial claims in the disputed region does not mean tensions will never resurface, analysts say.

Few expected the hubbub over long-running disputes involving seven claimants to fade so dramatically following the ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague on July 12 last year, but a new administration in the Philippines, the country that instituted the proceedings, swept tensions under the carpet.

However, many diplomatic and legal experts say the lull is just temporary and the ruling, which unequivocally rejected China’s expansive claims, will remain a major source of tension in the region for years to come.

The unanimous court ruling, which rejected Chinese claims based on historic rights and Beijing’s vaguely articulated nine-dash line, was one of China’s biggest diplomatic setbacks in decades and Beijing initially reacted indignantly to it. On top of its hardline approach of non-involvement and non-compliance in the case, it launched a propaganda blitz to belittle the ruling as part of a US-led attempt to encircle and isolate China.

But after reviewing how they could have got it so wrong, top leaders in Beijing now appear emboldened rather than deterred and have consolidated and expanded China’s presence in the contested waters, accelerating the militarisation of man-made features.

That build-up, criticised by the US and its allies as “dangerous and destabilising”, had startled regional neighbours who feared incurring Beijing’s political wrath or worse if they pressed China on the ruling, said Carlyle Thayer, emeritus professor of politics at the Australian Defence Force Academy, who described the ruling as being in “legal limbo and dead in the water”.

“As long as the parties to the award [China and the Philippines] do not comply, and other nations refrain from protesting, that gives rise to the supposition that the international community has acquiesced,” he said.

But Le Hong Hiep, a researcher at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said the ruling had set an important precedent and would not fade into oblivion, despite Beijing’s wishes.

“The ruling is like a stone inscription, not easily erased, and it will remain a strategic liability to China’s South China Sea policy for years to come,” he said.

Analysts say Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, sworn into office less than two weeks before the court handed down its ruling, has been the biggest game changer, surprising the world by setting the ruling aside in his abrupt pivot from Washington to Beijing.

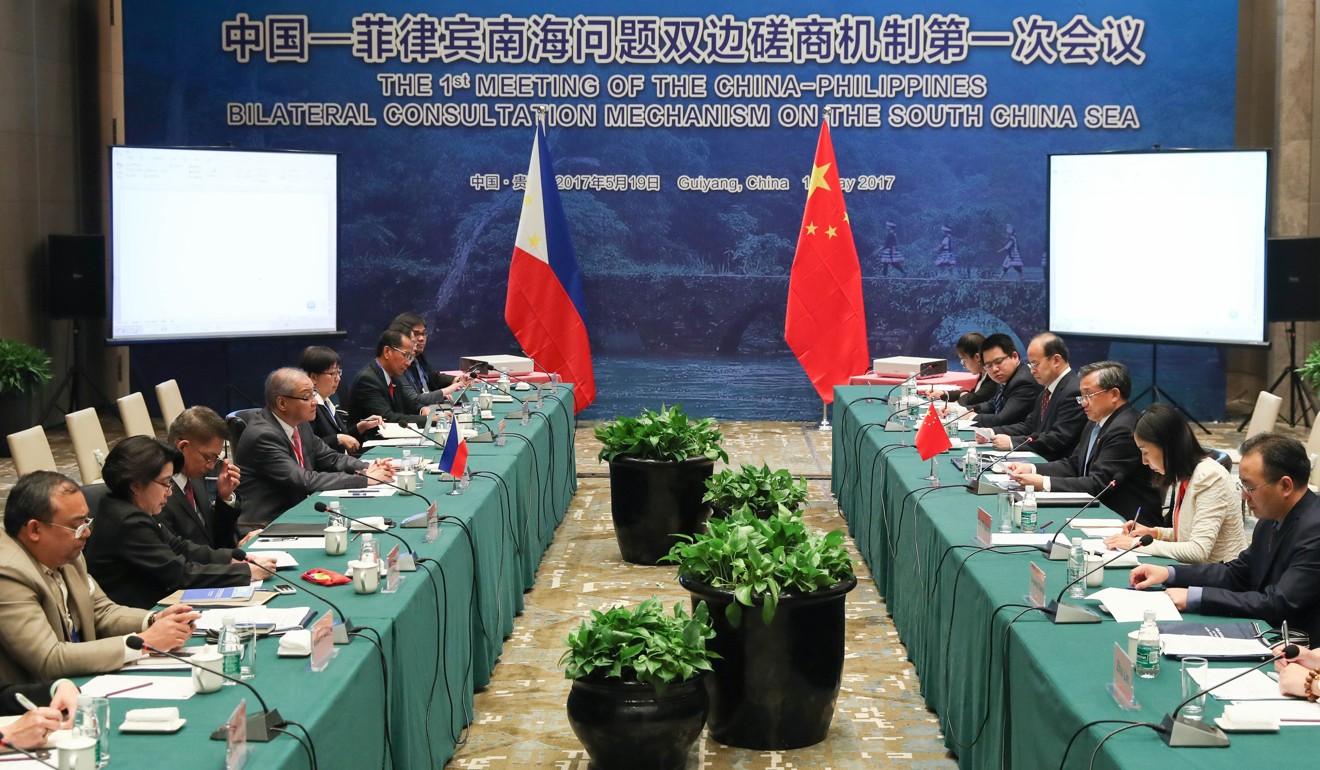

Jay Batongbacal, a legal expert at the University of the Philippines, said China and the Philippines, eager to repair damaged ties, had deliberately chosen not to discuss the ruling bilaterally or at multilateral events.

“Both countries, however, are fully aware of the ramifications of the ruling to their respective legal positions in the South China Sea, but are taking care to avoid the issues in order to cultivate and improve their economic and political relations,” he said.

Bonnie Glaser, of the Washington-based Centre for Strategic and International Studies, said Duterte’s change of heart had forced the hands of other nations that were supportive of the ruling.

“How can other countries care more about it than the Philippines which brought the initial case against China?” she said.

Batongbacal said China realised that a second legal suit from another claimant state, such as Vietnam, was “a plausible and real threat that cannot be taken lightly”, and was treading carefully to avoid such an eventuality, while its military activities in the South China Sea were “an attempt to demonstrate the difficulty or impossibility to asking China to step back from its expansive claims”.

Meanwhile, in the Philippines, Duterte’s decision not to trumpet the ruling had been widely criticised and his pro-China stance remained “his weakest point in an otherwise healthy approval rating”.

Chinese experts say Beijing’s economic might had helped it silence Southeast Asian nations, but tensions could resurface if they grew disappointed with Beijing’s largesse.

“Obviously, few nations in the region want to irritate China for the time being considering China’s growing military and economic clout, but that doesn’t mean the issue has gone once and for all,” said Zhang Mingliang, a Southeast Asia analyst at Jinan University in Guangzhou.

Beijing could not afford to feel complacent, he said, because none of the rival claimants, including Vietnam, Malaysia and Brunei, had expressly dismissed the ruling or made any compromises over their territorial claims.

“There is no use to pretend it did not happen because the ruling has set the basis for a new set of rules of the game, which will have far-reaching implications on how we should proceed with our claims,” Zhang said. “It’s become even more challenging as we need to come up with ways to solve the dispute by avoiding another similar lawsuit and accommodating each other’s concerns.”

Du Jifeng, a Southeast Asian affairs expert at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said Southeast Asian nations had been caught up in the growing rivalry between China and the United States in the Asia-Pacific region.

“Smaller nations do not want to choose side between the two powers,” he said. “China apparently wants to allay their security concerns about its meteoric rise and ultimate ambitions by accelerating talks on a long-stalled code of conduct in the South China Sea.”

A joint study released last week by US and Chinese experts from more than a dozen think tanks and universities painted a rather grim picture of the South China Sea dispute.

While the Americans warned of the danger of the South China Sea becoming “the crucible for US-China competition”, the Chinese side bluntly said ineffective management of the differences and frictions between the world’s top two economies could lead to armed conflict.

“For the first time in the past 100 years, China and the United States are facing head-on conflict of interests in the Asia-Pacific region,” the Chinese experts said.

US experts involved in the study said the Chinese military appeared to harbour a starker view of the possibility of conflict.

“Overall, whereas in US defence thinking China poses a potential long-term challenge to what has hitherto been unquestionable US military superiority in the Asia-Pacific region, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that in Chinese defence thinking, the US is viewed as a more basic threat to Chinese national security and an obstacle to Chinese regional ambitions,” they said.

Despite perceptions of a decline in Washington’s regional influence given US President Donald Trump’s isolationist agenda, Thayer said there were growing signs Washington was pushing back against China, with arms sales to Taiwan, the resumption of freedom of navigation missions by US warships in the South China Sea and overflights by US strategic bombers.

“China may be able to call some of the shots but it cannot confront the US Navy at the present moment,” he said.

Meanwhile, Thayer said, China’s Southeast Asian neighbours did not want to see a marked deterioration in relations between Washington and Beijing, which might lead to a disruption of international trade or even confrontation at sea.

Analysts said the temporary removal of territorial disputes in the South China Sea as a major irritant in China’s relations with Southeast Asian nations had opened the door for Beijing to use its economic strength to push its ambitious “Belt and Road” trade and infrastructure initiative.

They said China would redouble its carrot-and-stick approach in the region, enticing neighbouring states with economic benefits while assertively exercising jurisdiction over the South China Sea, but some expressed doubts about the long-term effectiveness of that strategy.

James Chieh Hsiung, a professor of politics at New York University, said Beijing’s reliance on offers of material goodies showed it was aware it risked isolation due to its communist ideology and America’s encirclement policy.

“What Beijing does not realise is that other than economic might, a giant power can lead only if it has soft power,” he said. “Part of the sources of soft power is whether China can demonstrate it has the ‘moral authority’ to inspire other nations to follow its leadership. The scofflaw stigma that came as a result of China’s summary repudiation of the final award, no matter how flawed it may be, cannot be shaken off by just ignoring it, as China has been doing.”

Batongbacal said Beijing was happy the disputes had been put to one side thanks to its high-handed approach and chequebook diplomacy, but it remained deeply insecure amid simmering tensions with Vietnam, the US and American allies such as Japan and Australia.

“While it is indeed pushing and flaunting its political economic and military power, it is not yet acting as a real leader that inspires full trust and confidence,” he said. “At this stage it is still buying the peace of its neighbours.

“At best, China is still consolidating massive gains under the new situation, and it knows that it can only maintain those at very high cost over the long run, and that the region’s current apparent calm may not last very long.”

Thayer said China appeared more adept at exercising negative power by disrupting initiatives with which it disagreed, than it was at employing positive power – unveiling initiatives others would follow.

“The key players in Southeast Asia will continue to modernise their military forces, hedge in their relations with Beijing and encourage the United States to remain engaged both economically and militarily,” he said.