Is China chipping away at the Asean bloc?

Beijing is forging stronger bilateral ties with its Southeast Asian neighbours, taking attention away from relations between the organisation’s members, observers say

If the last few weeks are any guide, China’s ties with its Southeast Asian neighbours are on the up.

There’s been a flurry of top diplomatic and military engagement between China and Myanmar, Vietnam and various other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean).

In part, it reflects a change in tack Beijing has taken to try to dispel some of the suspicions in the region over its growing economic clout and militarisation of the South China Sea, one of the world’s most important waterways.

It has done this by a combination of one-on-one diplomatic and economic support.

But diplomatic observers say that by pulling its neighbours closer, Beijing is stretching ties between other countries in the region, testing bonds within the Asean bloc on big issues like the South China Sea.

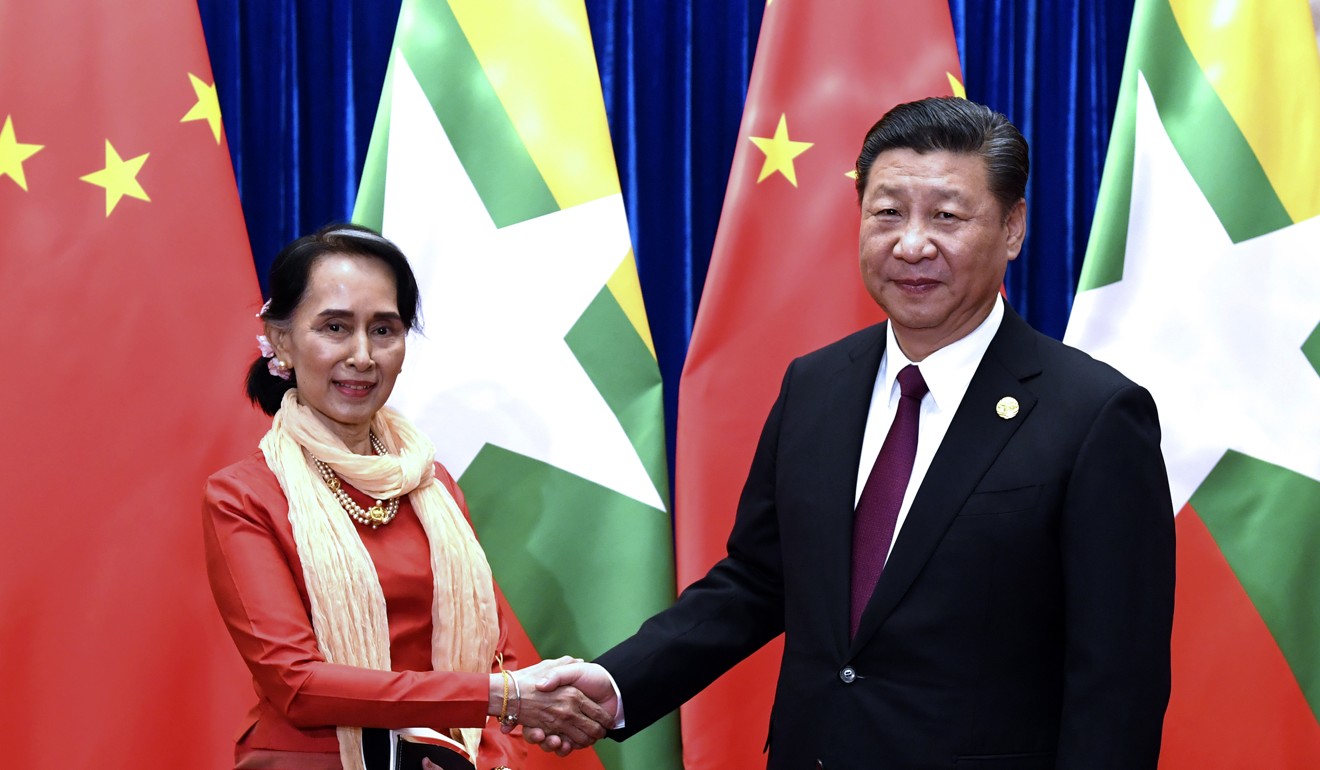

China’s stepped-up engagement was on show in Beijing on Friday when Chinese President Xi Jinping held talks with Myanmese State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi. Myanmar and Suu Kyi have been under fire for their handling of the Rohingya crisis in which more than 600,000 people in Rakhine state have been displaced. But on Friday Xi was talking up ties with Myanmar, saying Beijing will see the China-Myanmar relationship from a wider, strategic point of view.

The talks came after a state visit by Xi to Hanoi and Premier Li Keqiang to Manila last month. The militaries of China and Vietnam are also teaming up for 10 days of naval drills in the Gulf of Tonkin this month.

One important sign that this renewed engagement is paying off came last month at the Asean summit in the Philippines, where the bloc avoided all mention in its official statement of China’s militarisation of the South China Sea. That’s a big shift from just a year earlier when under the chairmanship of Laos, the statement said some member states were concerned by “land reclamation and escalation of activities” in the disputed waters.

Jay Batongbacal, associate professor at the University of the Philippines College of Law, said China had repeatedly stressed the need to resolve maritime disputes through bilateral talks but was creating a network of ties that put itself at the centre of regional power.

“It is naturally weaving a tapestry of economic and political relations revolving around itself as the common bilateral partner,” Batongbacal said.

“Given that most Asean countries already have China as their leading trading partner, the natural concern is that in doing so Asean may be losing some or much of its centrality as its members must then pay increasing high attention to China relations rather than the intra-Asean relations.”

The biggest change in relations can be seen with the Philippines. Just last year, tense ties between Beijing and Manila peaked when an international tribunal in The Hague found in favour of the Philippines in a maritime dispute over the South China Sea.

The administration of former president Benigno Aquino had asked the tribunal to assess the legitimacy of China’s claims to vast parts of the waters. The tribunal rejected China’s claims but Beijing refused to acknowledge the ruling.

A year down the track and China has pledged a series of investment deals under the new administration of Aquino’s successor, Rodrigo Duterte. Chinese companies are promoting their wares in the Philippines, Beijing has given weapons for Manila’s crackdown on drugs, and China has vowed to build infrastructure in Duterte’s hometown Davao.

Tang Siew Mun, head of the Asean studies centre at the ISEAS-Yusof Ishak Institute in Singapore, said Asean was concerned about China’s use of bilateral ties to limit the bloc’s strategic space and autonomy.

“Such concerns apply to not only China but any other major powers that want to bend the group to their strategic interests,” he said.

But change could come from at least two quarters, including Singapore, which will be taking over Asean’s chairmanship next year. Singapore has been a vocal critic of China’s manoeuvring in the South China Sea and could nudge Asean to take a stronger stand on the dispute.

At the same time, Asean members states have been improving ties with not only China but other powers as well, according to Dindo Manhit, from the Stratbase Albert del Rosario Institute in the Philippines.

In the sidelines of the Asean summit in Manila, representatives from the United States, Japan, India and Australia met for the first time in a decade, marking the revival of a regional coalition to lock horns with rising China.

Du Jifeng, from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, said Beijing still needed to be cautious about potential flashpoints in the South China Sea given that Duterte’s policies could change at any time.

“It is a strategic issue to play a soft or tough stance, but when it comes to core issues with national interests, such as territorial sovereignty in the South China Sea, no country would want to the soft one,” Du said.