Is China headed for a diplomatic crisis of its own making?

As Beijing boosts its global profile, foreign policy establishment worries about ageing senior diplomatic line-up and a shortage of first-rate younger diplomats

As Beijing seeks to accelerate China’s rise to superpower status, the expanded global ambitions set out by President Xi Jinping may have already hit a snag.

While Americans worry about US President Donald Trump’s inward-looking vision of Washington’s global role and the steep budget cuts he has proposed for the State Department, which many warn are causing a US foreign service brain drain, Beijing seems to have a talent gap of its own to deal with.

With China becoming increasingly assertive on a range of global issues, its diplomatic service is expanding at a dazzling speed.

However, the average age of China’s more than 5,200 diplomats stands at around 38, with nearly half of them below 35, mostly entry-level or inexperienced diplomats and youth hires, according to state media reports.

There are growing concerns within the foreign policy establishment about an ageing senior diplomatic line-up and a noticeable shortage of first-rate younger diplomats with adequate international exposure who are capable of rising to the many challenges facing China as it increases its global prominence.

Compounding matters, say people in the know, there have been widespread complaints among professional diplomats about repeated delays in the reshuffling of key diplomatic posts, especially top overseas ones.

For example, Chinese ambassador to the US Cui Tiankai reached the statutory retirement age of 65 for cabinet-level ministers in October. But Cui, who has spent almost five years in the Washington job, is believed to have been asked to postpone his retirement amid heightened trade tensions between the two countries.

“The US-China relations are at a critical moment and his expertise is of prime value at the moment. It would be imprudent to let him go due to mere technicality,” said Gal Luft, a co-director of the Washington-based Institute for the Analysis of Global Security.

While Cui may be an exceptional case during a rocky time with Washington, Luft said more such exceptions were being made, and the retirement age was not as sacrosanct as it once was for Beijing.

Despite growing calls for the logjam to be cleared, diplomatic sources and pundits say it has worsened over the past five years under former state councillor Yang Jiechi, a Politburo member who outranks Foreign Minister Wang Yi.

It has not only had adverse implications for individual careers, including those of many distinguished diplomats, and hit morale in the diplomatic service, but it could also undermine Beijing’s increasingly bold approach to expanding its influence in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond.

“The reality of the diplomatic service can hardly square with Xi’s stated agenda of taking China closer to centre-stage in the world, or the need to deal with mounting diplomatic challenges and uncertainties,” said a senior diplomat who spoke on condition of anonymity.

Despite the rapid ageing of Xi’s diplomatic team, the process of naming successors to a number of important foreign policy posts has largely stalled.

Pang Zhongying, a Beijing-based international affairs expert, said delays in finding replacements for senior diplomats had inevitably “disrupted the career development of younger talent” and had probably sparked an exodus of mid-career diplomats.

In an article published last year on the website of the party mouthpiece People’s Daily, Professor Wang Yizhou and another Peking University academic said quite a few Chinese diplomats were leaving their posts every year.

Citing scattered official data, they said 164 diplomats had quit between 1998 and 2002, with 80 per cent of them under 35.

They also warned that the quality and quantity of China’s diplomatic corps lagged its diplomatic ambitions.

“Compared with other international powers, the number of Chinese diplomats does not match our national strength and global standing,” they said.

The authorities had tried a slew of measures to attract and recruit young talent in a bid to expand the diplomatic corps, they said, but “the actual increase of diplomats is not significant compared to the soaring demand for diplomats”, with the gap appearing to have widened in recent years.

Pundits say it was previously unusual for senior Chinese diplomats to serve after they reached the age of 65, which is also the recommended retirement age for cabinet ministers and most top provincial cadres. A less stringent rule applies to vice-ministers and deputy provincial officials, who are encouraged to step down after 63.

But the shortage of experienced diplomats has seen government advisers put forward proposals to raise the retirement age of senior diplomats.

In 2013, a political adviser from one of the country’s eight officially recognised non-communist parties suggested that ranking diplomats, especially ambassadors, should be allowed to serve beyond 65 due to the acute shortage of seasoned diplomats.

Some pundits, however, say the problem might not be as serious as it seems because China has been working to expand its team of professional diplomats in recent years.

They also said the current leadership attached much greater importance to foreign policy issues, and the promotions of top diplomats in recent months were a sign Beijing was addressing the talent shortage, adding that they had given a much-needed boost to plummeting diplomatic morale.

Yang, a former foreign minister who will turn 68 in May, was elevated to the Communist Party’s decision-making Politburo in October, making him the first foreign policy chief to be a member of the party’s top echelon of power since former vice-premier Qian Qichen stepped down in 2003.

Half of China’s six deputy foreign ministers have reached or are approaching the retirement age of 63, while seven of the 10 top-ranking Chinese envoys to major powers in Asia, Europe and America are already over the same retirement age.

Ambassadors to international and regional organisations such as the United Nations, the World Trade Organisation and the European Union have the same protocol rank as deputy cabinet ministers, as do the country’s ambassadors to the United States, Russia, Britain, France, Japan, Germany, Brazil, India, Egypt and North Korea.

Ambassador to Britain Liu Xiaoming, 62, and ambassador to North Korea Li Jinjun, 61, are among the youngest, but like Cui Tiankai, ambassador to Russia Li Hui is already over the statutory retirement age of 65.

Li Hui, China’s envoy to Russia since 2009, is also one of the country’s longest-serving ambassadors.

The average tenure of an ambassadorship is under four years, but Cheng Yonghua, 63, has served as ambassador to Japan for more than eight years. Liu has been ambassador to Britain since 2010, as has ambassador to Egypt Song Aiguo, 64. Ambassador to Brazil Li Jinzhang and ambassador to Germany Shi Mingde have been in those posts for some six years.

The veteran diplomats’ protracted tenures are generally seen as recognition of their ability to handle China’s complex relations with major powers.

But they have also laid bare the embarrassing fact that there might not be good candidates to replace them in the absence of a professional mechanism for identifying and grooming career diplomats.

“Are those diplomats really indispensable and irreplaceable? Why should they be allowed to serve unusually long terms at the expense of the normal diplomatic succession mechanism?” asked Zhang Tuosheng, director of the Centre for Foreign Policy Studies at the China Foundation for International and Strategic Studies.

Ma Zhengang, a former Chinese ambassador to Britain and former president of the China Institute of International Studies, said Beijing faced growing challenges in strengthening its professional diplomatic service.

“Apart from foreign language proficiency, top-ranking diplomats need to have extensive experience and the ability to grasp complicated policy issues and it usually takes many years, if not decades, to groom ambassadors and ranking diplomats,” he said.

“It’s true that we are seeing delayed appointments in some of the top overseas posts, but then it is also understandable because seasoned diplomats are usually difficult to replace.”

Wang Yi, 64, was promoted to state councillor, succeeding Yang, during last month’s annual legislative meeting. The two men are set to continue to lead the diplomatic service during Xi’s second term, making the ageing problem appear even more obvious and acute.

However, three deputy foreign ministers – 64-year-old Zhang Yesui, Li Baodong, 63, and Xie Hangsheng, 63 – are expected to step down in the coming months, boosting the promotion prospects of the four assistant ministers – Qian Hongshan, 54, Li Huilai, 58, Qin Gang, 52 and Chen Xiaodong, 52. Those who do climb the ladder will be following in the footsteps of 58-year-old deputy minister Kong Xuanyou, who was promoted from assistant minister late last year.

The Chinese government has also shrugged off ageing concerns, citing the rise of a new generation of top diplomats such as Zheng Zeguang and Le Yucheng, who are both 54.

Zheng is deputy minister in charge of North America and Oceania and Cui’s most likely successor in Washington.

Le, who was Yang’s deputy at the Central Foreign Affairs Office, was last week named deputy foreign minister, in line to become the executive deputy minister when Zhang Yesui steps down. Like Li Huilai, Le is a Russian expert and a former assistant minister. He appeared to have Xi’s blessing in 2014 when he was posted to India ahead of the president’s visit to the country.

But pundits caution that China risks seeing a generational gap in the foreign service, with many important roles likely to be left unfilled when the bulk of the country’s top-ranking diplomats step down in the next few years.

If the problems are not properly dealt with, they warn, foreign service morale could dip further, imperilling the great power diplomacy that Xi sees as an integral part of his Chinese dream of national rejuvenation.

“I should think that any diplomatic service worth its salt would not have any senior diplomat who is indispensable,” said Steve Tsang, director of the London-based SOAS China Institute.

He said the common issue was the weakening of the institutionalisation process in China’s government under Xi.

“This will not be a problem in the short term, as Xi will keep people he trusts or wants in place for as long as he wants. But the weakening of institutionalisation will have a negative impact on grooming successive generations of diplomats and officials and weaken morale,” Tsang said.

“[That’s because] the best and brightest cannot map their own career progression path as well as previously – while those with connections will leapfrog over them or stay in high offices, blocking the brightest from progressing as they would have done under previous arrangements.”

Pang said that among other woes plaguing China’s diplomatic service, the country had made little, if any, progress in reforming its outdated recruiting practices despite more than two decades of talk about the importance of diplomatic professionalism.

“The failure to introduce long-overdue changes to the diplomatic system has probably resulted from stalled political reform and it underlines China’s inadequate capacity to drive the goals of major power diplomacy,” he said.

Zhang agreed, saying China’s diplomatic system had remained largely unchanged for years and lagged far behind developed nations in many ways.

“Unlike the United States and other Western countries, China does not have the revolving door mechanism [which allows fluid movement of people between the government and academic and other sectors] or another useful mechanism that allows retired diplomats to play significant roles,” he said.

The recruitment system remains largely unchanged, with most new hires being university graduates who join through the annual, national-level civil service exams. A one-off pilot scheme was introduced in 2000 to train ambassadors and about a dozen central and local government officials were selected to go through intensive, months-long training sessions. But the results were mixed, with not all of them deemed suited to becoming senior diplomats.

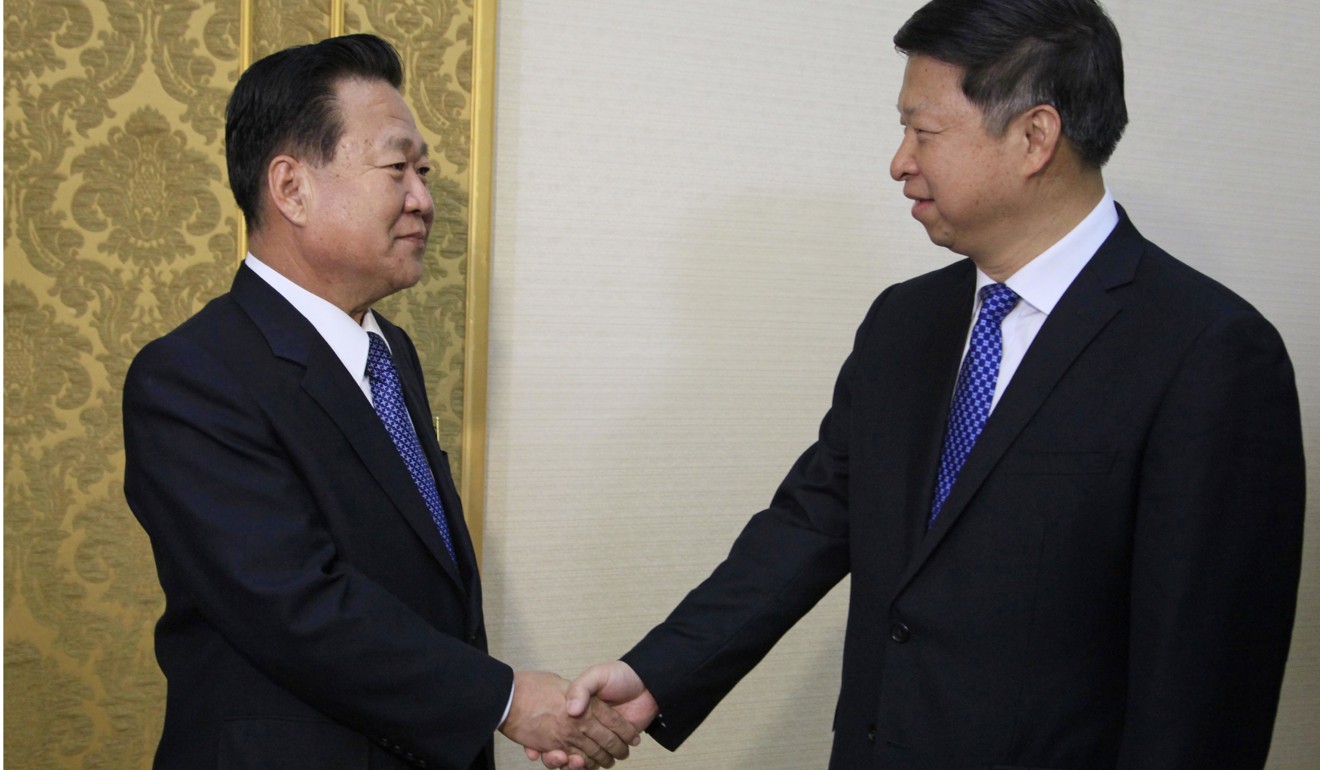

Song Tao, the head of the party’s International Liaison Department, China’s ambassador to North Korea Li Jinjun and Deputy Foreign Minister Xie Hangsheng were among those involved in the pilot scheme who did go on to get top diplomatic jobs.

As China’s military and economic clout have grown over the years, the army and many other party and government agencies have gained more sway in the country’s diplomatic hierarchy at the expense of the foreign ministry, which has seen its role diminished to a largely operational one.

Several Beijing-based foreign diplomats said they were having difficulty figuring out how to approach the Chinese leadership, which was largely inaccessible, or who were the right people to talk to, especially during periods of power transition.

They said most members of the diplomatic corps in China had come to realise through years of ineffective communication with mid- and low-level bureaucrats that Wang Yi and his ministry played a diminishing role in Beijing’s diplomatic decision-making.

“We’ve learned it the hard way as the messages we tried to convey to real decision-makers often got lost somewhere in the bureaucratic process,” said a European diplomat who declined to be named.

Additional reporting by Wendy Wu