What to look for when the leaders of China, Russia, Iran and India meet for this year’s Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit

China and Russia’s stance on the Iran nuclear deal will be a top issue at the regional security summit in Qingdao

With all eyes on the upcoming US-North Korea leaders’ meeting, the weekend summit of a China-led regional security bloc has gone largely under the international radar.

But when the annual Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) summit gets under way in the Chinese port city of Qingdao on Saturday, the leaders from the eight-member bloc are expected to address the big global issues, from the tensions on the Korean peninsula, to the Iran nuclear deal and US trade policies.

Beijing will be looking to press a series of key cross-border matters, particularly the “Belt and Road Initiative”, and greater cooperation to combat the “three evil forces” of terrorism, extremism and separatism, according to state-run Xinhua. Drug trafficking and cybercrime are also on the agenda.

The SCO was set up in 2001 with six member countries: China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. It expanded to eight last year with the admission of India and Pakistan. The bloc also has four observer states – Afghanistan, Belarus, Iran and Mongolia – and six dialogue partners, including Turkey, a member of Nato.

The Qingdao gathering coincides with the G7 summit in Canada, a group of seven major advanced economies, six of which are Nato members.

The SCO’s role has also expanded over the years, from regional security to political and economic cooperation, prompting critics to characterise it as a post-cold war Eurasian counterbalance to Nato.

Here are some of the big issues set to come up at the summit:

The Iran factor

The meeting will be the first overseas trip for Iranian President Hassan Rowhani since Trump decided in early May to pull out of the 2015 Iran nuclear deal, a withdrawal opposed by Moscow, Beijing and several major European powers.

The deal eased economic sanctions on Iran in exchange for restrictions on its nuclear facilities and, as signatories, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin are likely to use the summit to show symbolic support for the agreement.

Artyom Lukin, an international politics expert at Far Eastern Federal University in Vladivostok, said the final declaration of the summit “will probably mention that the [Iran deal] should continue to be adhered to by all the parties concerned”.

“However, it’s unlikely that the SCO will put direct and overt diplomatic pressure on the US,” Lukin said.

He said Moscow and Beijing were more likely to pursue the matter through the P5+1 mechanism, which comprises the five permanent members of the UN Security Council plus Germany, another signatory to the deal.

Nevertheless, Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying said China did not want Iran overshadowing the summit.

“We hope all parties focus on the theme of the summit,” she said on Thursday.

The Xi-Putin connection

Beijing and Moscow have put aside their differences and edged closer as each country has hit turbulence in their relations with Washington.

On Wednesday, Chinese state broadcaster CCTV aired an interview with Putin, in which the Russian leader played up his personal relationship with Xi in a recollection of the two celebrating his birthday in 2013.

But Lukin said Russia’s enthusiasm for this year’s summit was in response to the SCO’s admission of India and Pakistan as full members.

“China has been far less enthusiastic about the enlargement, particularly with regard to the inclusion of India. There are concerns that an SCO with more members will become less effective and less capable,” he said.

“Thus Russia will seek to prove that the inclusion of India and Pakistan, potentially followed by other countries such as Iran, makes the SCO ever more relevant, effective and capable.

“For Moscow, the SCO ... should also serve as one of the major bulwarks against, and an alternative to, the US-led Western hegemony.

“At the same time, an expanded SCO should act as a multilateral hedge balancing possible Chinese attempts to dominate continental Eurasia, even though this particular purpose is kept implicit and tacit.”

India, Pakistan and China

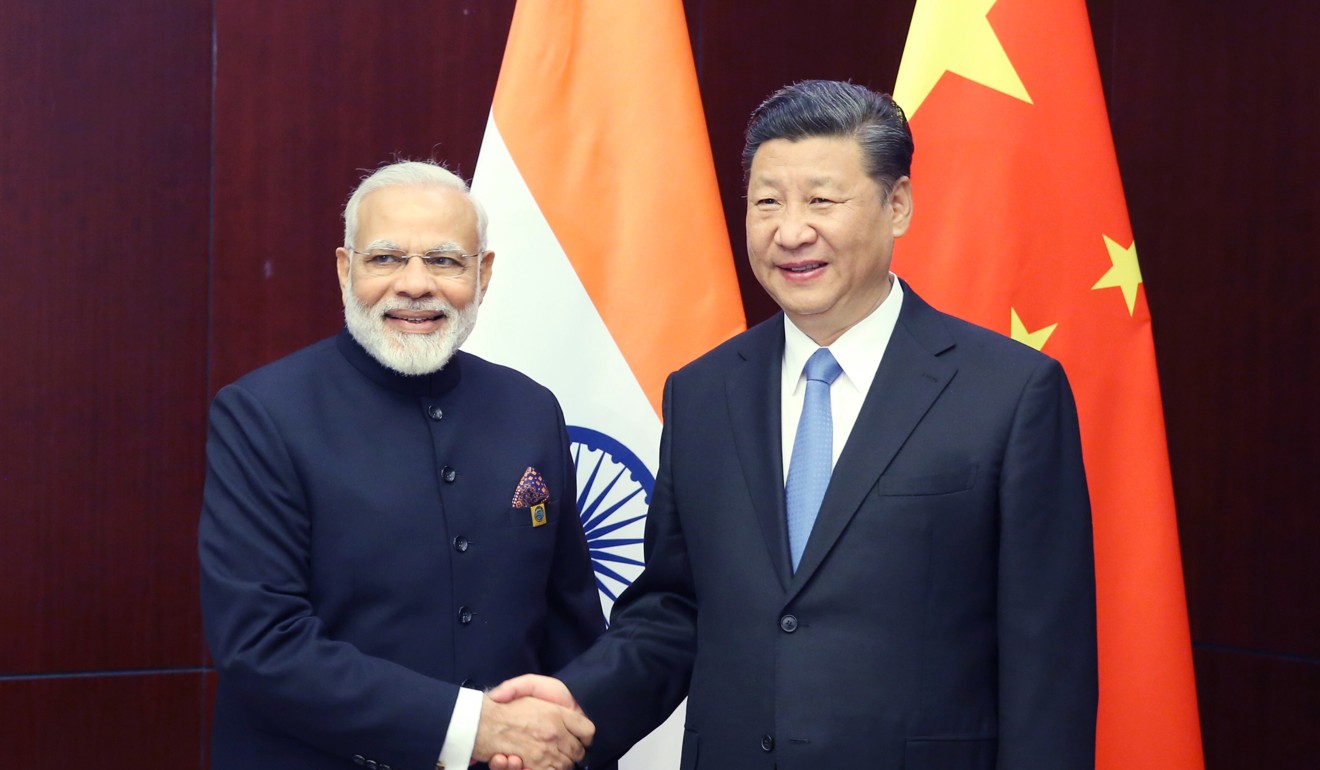

This weekend will be the second time in two months that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has visited China, reflecting efforts from both countries to improve relations strained last year by a protracted border dispute in the Himalayas.

In his address to an Asian security forum in Singapore last weekend, Modi studiously avoided any mention of the Quad – a grouping of US, Japan, India and Australia – a gesture that won him points with China’s foreign ministry.

However, Beijing has yet to secure Delhi’s support for its vast belt and road infrastructure plan. India sees the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), a centrepiece of the plan that runs through disputed Kashmir, as violating its territorial sovereignty.

With India and Pakistan now aboard as SCO member states, academics specialising in Indian affairs expect some informal interaction between the nations’ leaders but no movement on belt and road projects.

“While there could be an attempt to inject fresh air to improve relations, India-Pakistan relations are very complex and it is very difficult to predict the exact dynamics,” said Rajeev Ranjan Chaturvedy, a visiting fellow at S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore.

India would prefer to focus at the upcoming meeting on counterterrorism, cross-border energy, non-traditional security and development cooperation, according to Chaturvedy.

Madhav Nalapat, a professor of geopolitics at Manipal University, said that “unless issues are related to a part of the CPEC passing through territory that is Indian but under the illegal occupation of Pakistan”, progressive discussions on the belt and road would not take place.

Modi will meet Xi again on Saturday on the summit’s sidelines.

Xinjiang and Central Asia

Human rights groups and senior US officials have been vocal in their criticism of Beijing’s sweeping crackdown on religion and tightened security measures in its far western region of Xinjiang, home to one of the biggest Muslim groups in the country.

Laura Stone, US acting deputy assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs, said in Beijing in April that the United States was deeply concerned about China’s detention of at least “tens of thousands” of ethnic Uygurs and other Muslims and could take action to censure China.

In recent months, thousands of Uygurs deemed “prone to extremist influence” were reportedly detained in “re-education camps” in Xinjiang, with critics saying the area has become a “massive police state”.

Alarmed by terror attacks in Europe and the spread of Islamic State militants from the Middle East to other parts of the world, China is watching anxiously for any sign of extremist influence among its population of 23 million Muslims – mainly Hui and Uygurs.

However, Beijing’s campaign against terrorism and Islamic extremism have raised eyebrows with some Central Asian SCO members bordering the region. Muslims from Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan have also reportedly been targeted in Xinjiang.

In a meeting in Beijing in late May, Kazakhstan’s foreign ministry raised concerns about ethnic Kazakhs being detained in China, according to the ministry’s website. But the issue is unlikely to come to the summit table, making way for broader regional concerns.

“The SCO is an institutional mechanism that allows the Central Asians to pursue multi-vector foreign policies, manoeuvring between the Eurasian great powers, China and Russia, and now also India,” Lukin said.

China-Mongolia relations

Despite Mongolia’s status as an observer state, China will be watching the country’s new president, Khaltmaa Battulga, closely as he makes his first appearance at the SCO summit. Battulga won the presidency last year by running a populist campaign that was laced with anti-China rhetoric.

China and Mongolia have a close but tense history. Mongolia, which was ruled as a Chinese territory until 1911, has always suspected that one day its southern neighbour will try to reclaim the land it lost.

Meanwhile, Beijing exercised its economic and geographic strength to bring Mongolia to its knees in 2016 after it invited the Dalai Lama for a four-day visit. Mongolia then declared that it would not invite the exiled Tibetan spiritual leader for another visit.

Mongolia, an SCO observer state since 2004, has shown little interest in becoming a full member of the bloc, despite China raising the possibility in 2014.