From China to Central Asia, a regional security bloc’s long, slow march towards an alternative world order

The world’s attention was on Singapore and Charlevoix but the future may have been in the Chinese city of Qingdao

While the world was captivated this week by the globetrotting show of US President Donald Trump, another summit just days earlier suggested what an alternative world order might look like.

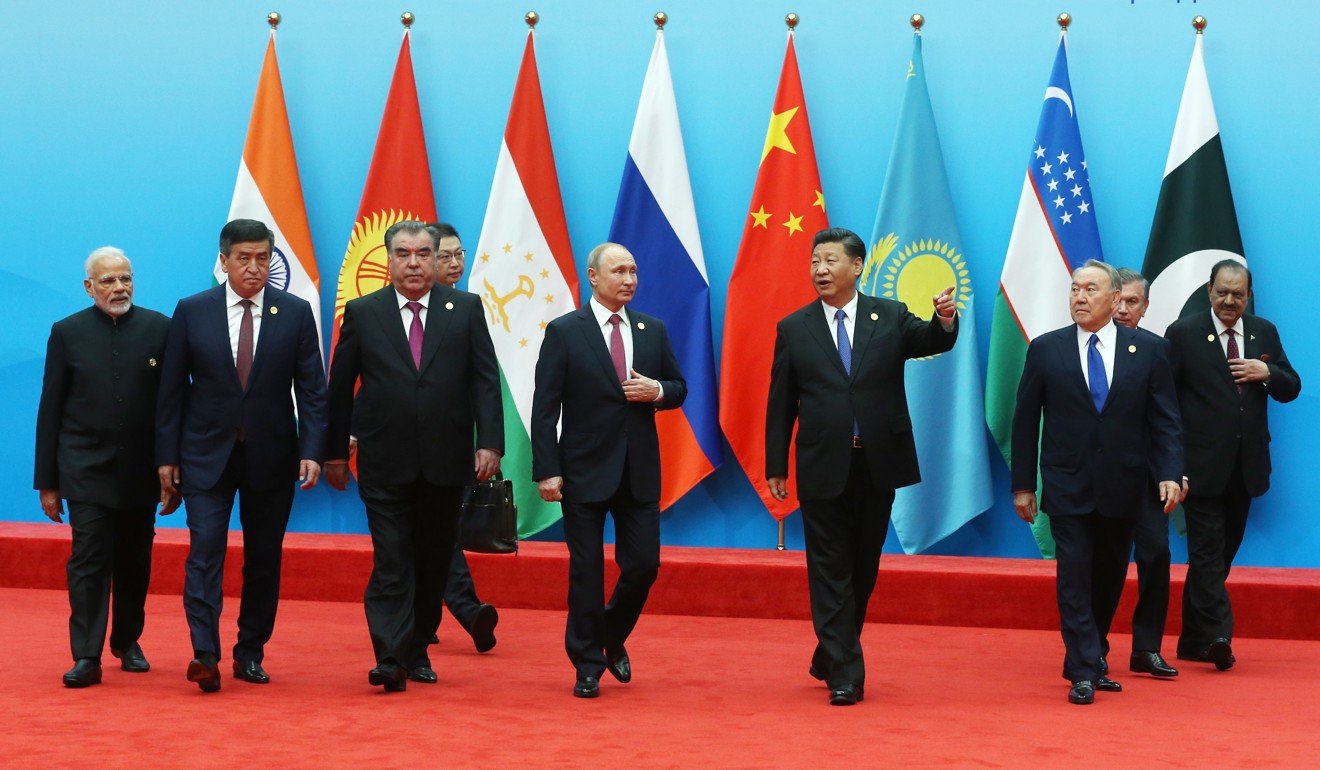

Various heads of state from member nations of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) met in the Chinese city of Qingdao for the bloc’s annual heads of state meeting.

The SCO’s activities have been limited in the decade and a half since it was formed but this year’s summit had some significant moments.

First and foremost was the presence of – and handshake between – Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Pakistani President Mamnoon Hussain. While the membership of the two regional rivals is likely to be a major block to future activity, the presence of their leaders showed some of the organisation’s potential. Modi’s attendance alone signalled that the world’s biggest democracy wanted to maintain strong links to this archetypal non-Western institution to make sure it had all of its international bases covered.

The event was also an opportunity for two of the West’s biggest pariahs, Iran and Russia, to grandstand.

In the past Beijing has sought to tamp down efforts by Iranian leaders to transform the summit into a chance to bash the West. Back in 2010, President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad was so disappointed by the SCO’s refusal to admit Iran over fears of antagonising the West that he skipped the summit in Tashkent and instead attended the Shanghai Expo. But in Qingdao, the group chose to unite to highlight their displeasure at renewed Western sanctions against Iran and the collapse of the Iran nuclear deal.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has also regularly used high-profile summits in China to show disregard for Western sanctions and the optics around Putin’s attendance were similar to many other previous events, though this time are topped with a medal for his “friendship” with China.

On the sidelines of the summit, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced that “no matter what fluctuations there are in the international situation, China and Russia have always firmly taken the development of relations as a priority”. On live television he then proceeded to give the Russian leader a gold medal lauding him as “my best, most intimate friend”.

Awkward phrasing aside, this is a clear signal that China is siding with Moscow in tensions between Russia and the West. While Beijing might not always approve of Moscow’s disruptive behaviour on the international stage, the reality is that the two powers will, under their existing leaderships, always stand together against the West.

And this signal by Beijing was the most notable point about this entire summit.

China has long treated the SCO with the reverence required of an institution that brings together the heads of state of a number of its allies and which it helped name, while at the same time disregarding it as a functional organisation. Beijing has been unable, for example, to realise some of its key ambitions with the group. China has sought to push the SCO towards greater economic integration and activity, something resisted by other members fearful of China’s further encroachment into their territories.

Moscow sees the SCO as a way to try to control Chinese efforts in Central Asia while the Central Asians broadly view it as a possible way to maintain a balanced conversation with their giant neighbours. Meanwhile, powers like Iran, India or Pakistan see it as an alternative international forum that they want to be involved in.

With the accession of India and Pakistan most observers in China fear that the organisation’s already limited ability to operate is going to be even further reduced.

Yet none of this detracts from the fact that for Beijing it is a forum which they are hosting which now brings together the leaders of over a third of the planet’s population. They are clearly the dominant player within it, and it is a forum in which Western powers cannot meddle.

This gives Beijing the perfect opportunity to show its stature on the world stage and its efforts to offer a more stable alternative world order to the chaotic one that is most vividly expressed by the Trump administration.

The SCO may have done remarkably little beyond hold big meetings and China’s activity in all of the SCO member states at a bilateral level is infinitely more significant than its efforts through the bloc.

But at the same time, this is a forum that has consistently met and only grown. Under its auspices, China has managed to slowly encroach on Russia’s military and political dominance in its own backyard, and has now persuaded the world’s biggest democracy that it is an important group to be involved in.

This slow march forwards stands in stark contrast to the imagery and disputes to emerge from the G7 summit in Charlevoix. And while the Western media may have largely ignored events in Qingdao for events in Canada and Singapore, the rest of the world is paying attention. An alternative order might be starting to crystallise, or at least one that has potential to deeply undermine the West’s capacity to determine the future of world affairs.

Raffaello Pantucci is director of international security studies at the Royal United Services Institute in London