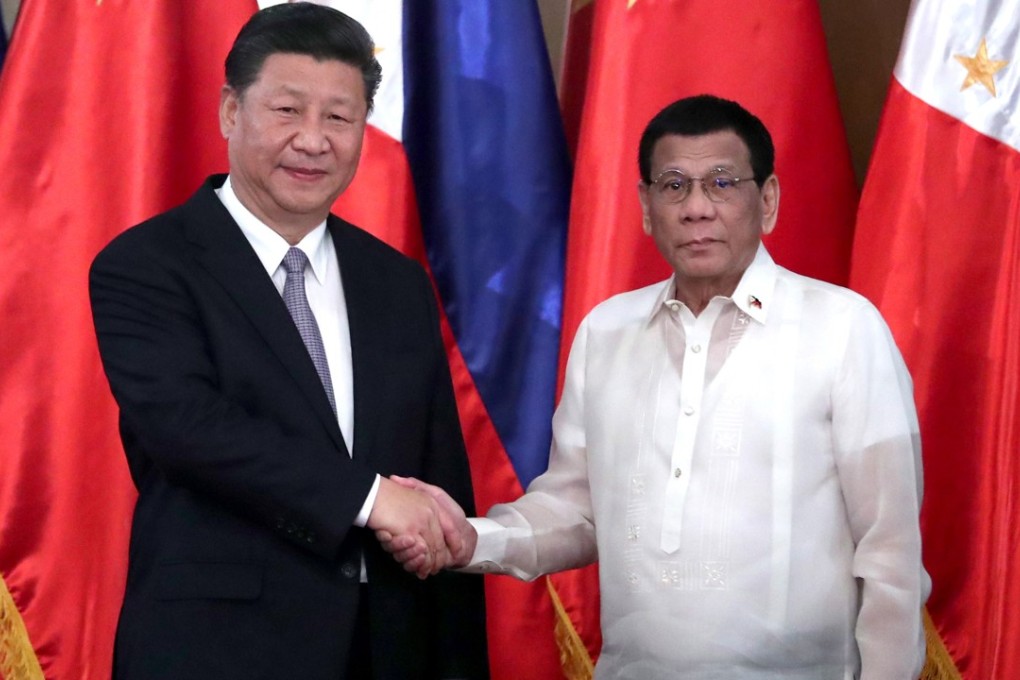

As Beijing and Manila shake hands on South China Sea energy deal, backlash from Filipino critics begins

- In Philippines, campaigners challenge Duterte’s assertion that Beijing’s control over disputed South China Sea is fait accompli they must accept

Manila defended its newly signed joint energy exploration deal with Beijing in the disputed waters of the South China Sea, after critics said the move undermined an international tribunal ruling in favour of the Philippines.

After a red-carpet welcome for Chinese President Xi Jinping at the Malacañang Palace in Manila on Tuesday, the two sides signed a memorandum of understanding for joint oil and gas development in the contentious waters, in another sign of Manila’s warming ties with Beijing under President Rodrigo Duterte.

The agreement comes at a time of intensifying tensions between China and the United States – a defence treaty ally of the Philippines – that have gone beyond their trade war to clashes over Chinese militarisation of the South China Sea.

In a joint statement released on Wednesday, the nations said the South China Sea dispute should not affect their cooperation.

They said the disputes should be resolved through peaceful negotiations among the claimants – a veiled reference to the US – and no side should resort to violence. Both nations should exercise restraint to avoid letting the disputes escalate.

Duterte said at the Asean regional summit in Singapore last week that China was “already in possession” of the South China Sea, so it made more sense to work with it in the resource-rich waters rather than create frictions.