Risk of US-China clash in South China Sea worries Philippine firms more than trade war

- Keeping sea lanes open is a main concern of members of American Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines

- Businesses were already hit by an inflation crisis when Beijing and Washington called their trade war truce

It’s an uneasy time for Asian nations as the rivalry between China and the United States intensifies and uncertainty hangs on whether they can resolve their trade war beyond the 90-day truce. In this special series the South China Morning Post explores how the China-US rivalry is affecting four countries in Asia. In the final part, Sarah Zheng looks at the Philippines.

With no clear end to the US-China trade war in sight, businesspeople in the Philippines – already hit by an inflation crisis – increasingly fear they could get caught in the crossfire if the confrontation between the two economic powerhouses spilled over into the South China Sea.

While Philippines President Duterte has pushed for a rapprochement with Beijing, lured by promises of massive Chinese investment in the country, the archipelagic state still maintains its long-standing defence treaty relationship with the US.

Although inflation in the Philippines eased off in November after surging to a nine-year high earlier this year of 6.7 per cent, the central bank has raised interest rates five times this year, citing “continued uncertainty” amid “tighter global financial conditions and trade tensions among major economies”, a loose reference to the impact of the US-China trade war.

“I’m hearing more [about] the South China Sea issue and the possibility of a military confrontation, than a cold war [that] turns into a hot war,” Ebb Hinchliffe, president of the American Chamber of Commerce in the Philippines, told the South China Morning Post.

While some of the business group’s members are feeling pain from the prolonged trade battle, their greater worry is that the conflict will spill over into the South China Sea, where Manila and Beijing are both claimants, bringing even bigger problems to the Philippines’ business community, Hinchliffe said in an interview.

“Existing companies are more concerned about keeping the sea lanes open and how it plays with the Philippine politics,” he said. “The Philippine government is shifting more towards China and less away from the United States, [while] the United States is confronting China.”

Those relationships “are what’s driving this uncertainty about the South China Sea or the West Philippine Sea issue”.

The South China Sea has long been a flashpoint for conflict in the region, particularly since the Philippine government filed and won a case against China’s “nine-dash line” claims in an international tribunal in 2016.

Duterte said at a regional summit in Singapore in November that if Sino-American tensions in the disputed waters were to escalate into war, the Philippines would be “the first to suffer”.

“China is there,” he told reporters. “That is a reality, and America and everybody should realise that they are there.”

As the months-long trade war drags on, Beijing has stepped up its efforts to assert its authority over the disputed maritime region.

Critics cite its building and militarising of artificial islands as well as the near-collision of a Chinese military ship with a US Navy ship as examples of its desire to push back against America’s presence in the controversial waters.

At the same time, annual Chinese investment under Duterte is growing, surging 67 per cent last year to US$53.8 million, compared with a year earlier.

Inflation woes already were weighing on Philippines business growth when the US and China agreed to a 90-day moratorium on new tariff increases at a meeting after the G20 summit in Buenos Aires on Saturday December 1.

But the appearance of a deal – even a temporary one – failed to prevent new doubts from surfacing about whether the trade war would end soon.

Benjamin Lim, general manager of the Lim Yee Wan Co hardware business in Binondo, a Manila district known as the world’s oldest Chinatown, blamed his slowing business this year on the trade war, rising inflation and the depreciating peso. Most of his products are imported from the US and sold domestically.

“This year has been poor,” Lim said. “It’s difficult in the sense that for us as an importer, we need to have a stable forex.

“Some of my suppliers come in and say, we hear the Philippines economy is booming,” he said. “But core business is not really that good. The buying power of the regular people is still so small, labour has been craving for us to give them more salary, but that is difficult for us also.”

Ernesto Pernia, the country’s socioeconomic planning secretary, has told the Post that the trade war could spur a shift across the global supply chain that would increase the Philippines’ exports by 5 per cent. Duterte, however, has blamed the inflation troubles on the US’ tariffs on Chinese goods, even as economists attribute the crisis mainly to higher government taxes and rice shortages.

The Philippine president’s effort to roll out the red carpet for Beijing has been received positively in many corners of the business sector.

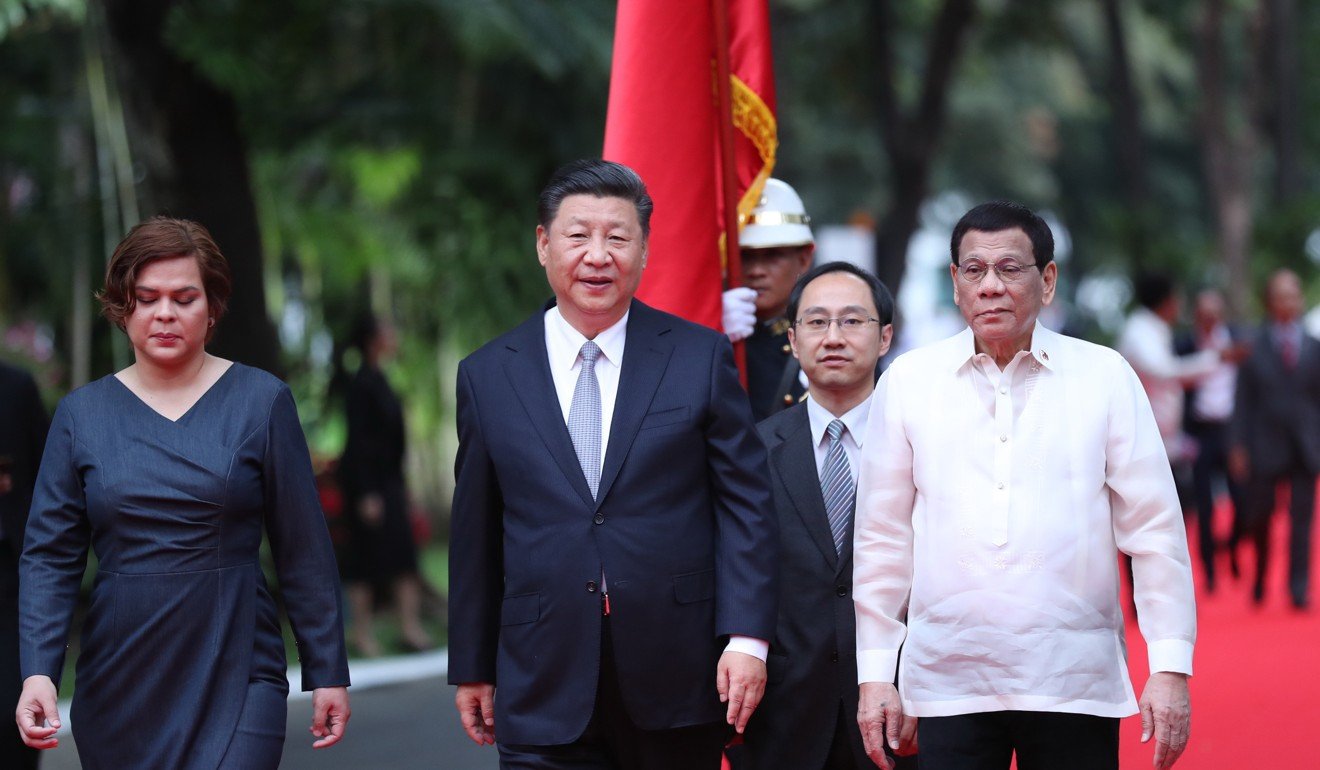

During Xi Jinping’s trip to the Philippines in November, the first by a Chinese head of state since 2005, the countries signed 29 deals. The list included memorandums of understanding for cooperation on Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative and joint oil and gas development in the South China Sea, and on infrastructure projects such as the 4.37 billion peso (US$214.6 million) Chico River Pump Irrigation Project.

Ricardo Visaya, administrator of the National Irrigation Administration, which is heading the China-funded Chico pump project, said he wanted to see “the friendship and the cooperation” between Beijing and Manila on Philippine development projects “continue for a long-lasting relationship”.

But others in the Philippines – both inside and outside the business community – are less thrilled by China’s growing presence in the country.

“What does a truly independent foreign policy look like?” Antonio Tinio, a Philippine activist and congressional representative of the Alliance of Concerned Teachers, said on the sidelines of a recent university forum. “It’s definitely not taking the side of either the US or China.”

The fact is, Chinese foreign direct investment in the Philippines remains relatively small, at least compared with investment from top investors such as Japan, the US and Indonesia.

Although Chinese investment in the country nearly doubled, year on year, in the first three months of 2018, it still accounted for just 3 per cent of total investment entering the country, according to the Philippine Statistics Authority.

Nevertheless, the Duterte administration’s focus on its “Build, Build, Build” infrastructure plan and regional development have spurred changes for major lenders, including the Manila-based Asian Development Bank, which is working with Japan on a new railway line connecting Metro Manila to Clark, a suburb of Angeles city in Pampanga province.

“We’ve had a really strong relationship with successive administrations, but this administration – the types of things that they do have significantly changed,” said Ramesh Subramaniam, director general of Southeast Asia for the Asian Development Bank.

“From the previous administrations, we were largely supporting the policy reforms, so that meant more budget support type of assistance. We are doing a lot more project-type investments now.”

Hinchliffe is dismissive of the naysayers, saying the priority is to create jobs in the country, even if they come from investment by China or others, to reduce poverty and establish a more stable government.

“We don’t welcome the Chinese,” he said. “We’re not going to open the doors and try to give them our secrets, [so they can come in] and then compete against us. But if they’re coming in and they’re creating jobs, it’s overall going to have a good benefit,” he said.

Notwithstanding the short-term challenges foreign businesses face in the country, including corruption, infrastructure deficiencies and the uncertainty of a pending tax bill, Hinchliffe said he is “very positive” about the Philippines’ long-term economic growth prospects, crediting infrastructure improvements and a booming middle class.

And yet, US influence remains strong throughout the Philippines. Despite China’s growing influence and the government’s friendly overtures to Beijing, a recent US survey by the Pew Research Centre found that 77 per cent of respondents in the country favoured the US as the global leader, compared with 12 per cent who preferred China.

“The Philippines is still a very pro-American country,” Hinchliffe said. “I’m talking about the people, not the administration. It’s kind of a love-hate affair at times with the government, but the people themselves … I wouldn’t say they’re anti-Chinese, they’re just pro-American.”

For Lim, the hardware manager whose family immigrated in the 1940s from Gulangyu, Xiamen, the Philippines’ geopolitical manoeuvring was irrelevant, he said, as long as it was good for his children and grandchildren.

“It doesn’t really matter if it’s from the US, or from China, as long as something is done,” he said.

But a Sino-US war in the South China Sea stemming from tensions that so far have been mainly confined to the trade realm, would severely hurt the country, he warned.

“That’s the worst thing that can happen in our time,” he said. “So let’s cross our fingers and hope that everything can be [settled] at the [negotiating] table.”