China’s promise of loan write-offs for distressed African nations barely dents a much bigger debt crisis

- Study finds no evidence of asset seizure by lenders or penalty on arrears, but researchers note a lack of transparency fuels suspicion of China’s intentions

- China’s lending to Africa stood at US$152 billion between 2000 and 2018, much of which went to Belt and Road Initiative projects

The study said China had cancelled interest-free loans amounting to US$3.4 billion in debt in Africa between 2000 and 2019. But China’s overall lending to Africa stood at US$152 billion worth of loan commitments between 2000 and 2018. The zero-interest loans come from China’s Ministry of Commerce as part of intergovernmental economic and technical cooperation agreements and average about US$10 million per loan, according to the study.

“In almost all of the countries where Chinese debt was cancelled – aside from high-profile cases in Iraq and Cuba – the cancelled debt was limited to mature, interest-free foreign aid loans that had gone into default,” Deborah Brautigam, a professor of international political economy and CARI founding director, said in the study.

Other authors of the report include Kevin Acker, a research manager at CARI and Yufan Huang, a research assistant at CARI.

Brautigam and her colleagues at CARI said China was yet to cancel concessional loans, or lines of credit and commercial loans to Africa which accounted for the lion’s share of debt to African countries. The billions of dollars of debt had gone into the building of motorways, ports, dams and railways.

However, when countries were not able to service their debts, the study said, they had to seek restructuring which could see the grace period, interest rate or maturity date varied or, rarely, through refinancing by taking a new loan to pay off an old loan.

Brautigam said normally, cancellation and restructuring were done loan by loan, not across an entire debt portfolio. She said that between 2000 and 2019, Chinese lenders restructured about US$7.5 billion and refinanced another US$7.5 billion (in Angola by the China Development Bank).

Despite growing criticism from Western countries, especially from the administration of US President Donald Trump, that China’s lending to Africa was creating debt traps, CARI said it did “not see China attempting to take advantage of countries in debt distress”.

“There were no ‘asset seizures’ in the 16 restructuring cases that we found. We have not yet seen cases in Africa where Chinese banks or companies have sued sovereign governments or exercised the option for international arbitration standard in Chinese loan contracts,” the study noted.

The report also concluded that there was no evidence of penalties on arrears. However, Chinese lenders preferred to address restructuring quietly, on a bilateral basis, tailoring programmes to each situation.

“The lack of transparency fuels suspicion about Chinese intentions. These patterns are likely to play out as Chinese lenders and African borrowers grapple with the impact of Covid-19,” Brautigam and her team said.

The study said several countries – including Mozambique, Cameroon, Zimbabwe, Niger, Ethiopia, Benin, Sudan, the Republic of Congo, Chad and Seychelles – had had their debt with Chinese lenders restructured when they fell into financial trouble.

For example, when Ethiopia was unable to service debt it had taken to build a modern railway with Djibouti, it sought help from Beijing and had its debt rescheduled by Export-Import Bank of China (China Exim Bank) by extending the repayment period from 10 to 30 years.

Ethiopia had borrowed US$2.92 billion from China Exim Bank of the US$4.2 billion needed to build the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway. China Export and Credit Insurance Corporation, known as Sinosure, claimed it had lost close to US$1 billion on the Ethiopia railway project, according to the researchers.

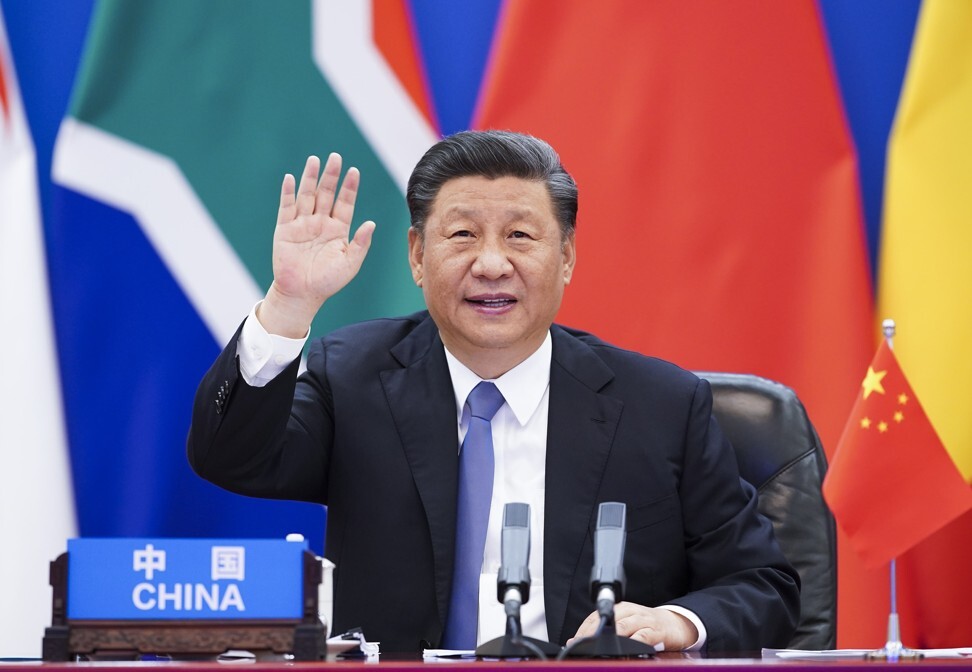

Besides cancelling interest-free loans for Africa, Xi also urged Chinese financial institutions such as the Export-Import Bank of China and the China Development Bank “to conduct consultations with African countries on commercial sovereign loan arrangements”.

Beijing’s agreement to jointly help poor nations through the G20 deal marks the first time China has joined a multilateral commitment to provide debt relief on government-to-government lending, according to the study.

“We expect China to honour this commitment for countries that request a moratorium,” the CARI researchers said.

The study, however, noted that the G20 deal only addressed bilateral creditors. Many low-income countries held substantial amounts from private creditors.

However, some countries such as Kenya have raised concerns that the G20 deal has restrictive clauses that bar them from taking up loans in the period the moratorium is in place.

Kenya said it was negotiating with China bilaterally for debt relief. By late last month, only 22 out of 77 eligible countries had started the G20 debt relief process.