China-EU investment deal: who’s the real winner after seven years of negotiations?

- Comprehensive agreement on investment will give European firms a ‘better chance to enter the Chinese market and increase competition between Chinese and European investors’, Fudan University’s Ding Chun says

- ‘The real winner is China, not the EU, even if the commitments/concessions that China promised would be eventually achieved,’ Justyna Szczudlik, head of the Asia-Pacific programme at the Polish Institute of International Affairs, says

“A level playing field, transparency and confidence in the rule of law are essential on both sides for business to thrive.”

Explainer | What is the China-EU CAI and how is an investment deal different from a trade deal?

After all, the goals in 2013 were modest – reducing investment barriers and legal uncertainty faced by European firms in China and boosting two-way trade to US$1 trillion by 2020.

But 2013 was a different era. Seven years ago, few people would have questioned the resilience of the EU-US transatlantic alliance, and any talk of a new cold war between China and the US would have been dismissed as rumour-mongering.

Fast-track to January 2021 and the world is deeply divided and polarised. Both Europe and the United States are battling a pandemic. The World Bank estimated global world output fell 5.2 per cent in 2020 – the worst since World War II – although China managed some growth.

“President Xi Jinping and European leaders jointly announced completion of the negotiations of the CAI,” China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi said in a year-end review published over the weekend.

“This not only injects great momentum into Sino-European cooperation but is also great news for the depressed world economy.”

Pundits generally agree that Beijing has emerged as the bigger winner, but opinions differ on its significance for Western economies and what it means for China’s economic recovery after the pandemic and its global ambitions in the face of international resistance.

Sourabh Gupta, a senior fellow at the Institute for China-America Studies in Washington, described the agreement as a milestone.

“For China, this is the most significant economic agreement, geo-economically, geopolitically as well as from a broad economic perspective, since the signing of its World Trade Organization Accession Protocol in 2001,” he said.

“It will be remembered in the future as the most economically meaningful instrument signed by China during its second phase of reform and opening up.”

The deal will deepen the economic ties between China and the EU

Wu Xinbo, director of the Centre for American Studies at Fudan University in Shanghai, said securing the deal with the EU put China in an “invulnerable position” and help insulate it from America’s efforts to exclude it from global trade and investment.

“The deal will deepen the economic ties between China and the EU, with negotiating a free-trade agreement being the expected next step,” he said.

“And it will also thwart the US’ plan to join hands with Europe and isolate China from the future of globalisation.”

US and EU demand China release citizen reporter Zhang Zhan, locked up for covering Wuhan coronavirus outbreak

Ding Chun, director of the European Studies Centre at Fudan University, agreed that the deal was more than just an investment pact.

“This will give a comparative advantage for European investment and technology. The CAI will give [European firms] a better chance to enter the Chinese market and increase competition between Chinese and European investors,” he said.

“It’s a comprehensive agreement, restricted not only to the field of investment, but also covering sustainable development, the environment and labour rights. It will give China a push to upgrade and improve its institutional arrangements, and will push it towards more high level, high standard agreements for future FTAs and other deals,” he said.

China-EU investment deal: ‘landmark’ treaty greeted with a shrug by underwhelmed analysts

Some said the deal was premature and could come at the cost of a reboot of the transatlantic alliance Biden has set as a priority in his multilateral approach to countering China.

George Magnus, a research associate at Oxford University’s China Centre, said the EU appeared to have conceded leverage for seemingly very little in return.

According to Gal Luft, co-director of Institute for the Analysis of Global Security, a think tank in Washington, the EU’s move was a deliberate attempt to take advantage of the power vacuum in the US.

“Concluding it in the interregnum period ensures that the outgoing administration will have no time to penalise Brussels while the new one will have no chance to weigh in,” he said.

“This shows that the EU, despite its misgivings about China’s behaviour and policies, wants to remain an independent player and is unwilling to be dragged into the US-China power struggle.”

Britain and EU strike post-Brexit trade deal

The deal has apparently irked both the outgoing administration of President Donald Trump and the Biden team. Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser nominee, called for “early consultations with our European partners on our common concerns about China’s economic practices”, while Trump’s deputy national security adviser, Matt Pottinger, lashed out at European leaders for taking Beijing’s pledge to honour labour rights at face value, “while it continues to build millions of square feet of factories for forced labour in Xinjiang”.

He was referring to the internment of ethnic Uygurs and other Muslims in China’s far western region, which Beijing has denied.

An EU document seen by the South China Morning Post confirmed that European leaders were aware of the deal’s possible repercussions on relations with the new US administration. But it insists that the deal “will not affect our commitment to transatlantic cooperation, which will be essential for addressing a number of the challenges created by China”.

“This agreement achieves more of a balance for the EU with China, and will give them more of a free hand when they negotiate with the United States,” Ding said. “The CAI will help give a chance for a ‘post-Trump’ era of world trade, that’s more about cooperation between the big economies of the world.”

From the EU’s perspective, it has its own challenges too. Apart from Brexit and transatlantic discord, it is trying to redefine itself on the global stage, with member states balancing between a desire for strategic autonomy and the need to collectively defend their common interests and values.

Gupta said that no matter what deals China worked out with the Europeans, transatlantic cooperation would supersede China’s ties with the US or the EU.

“Because the former is grounded in values and interests while the latter is grounded primarily in interests,” he said. “The EU’s statement is a bow to this obvious and, in its view, preferred reality.”

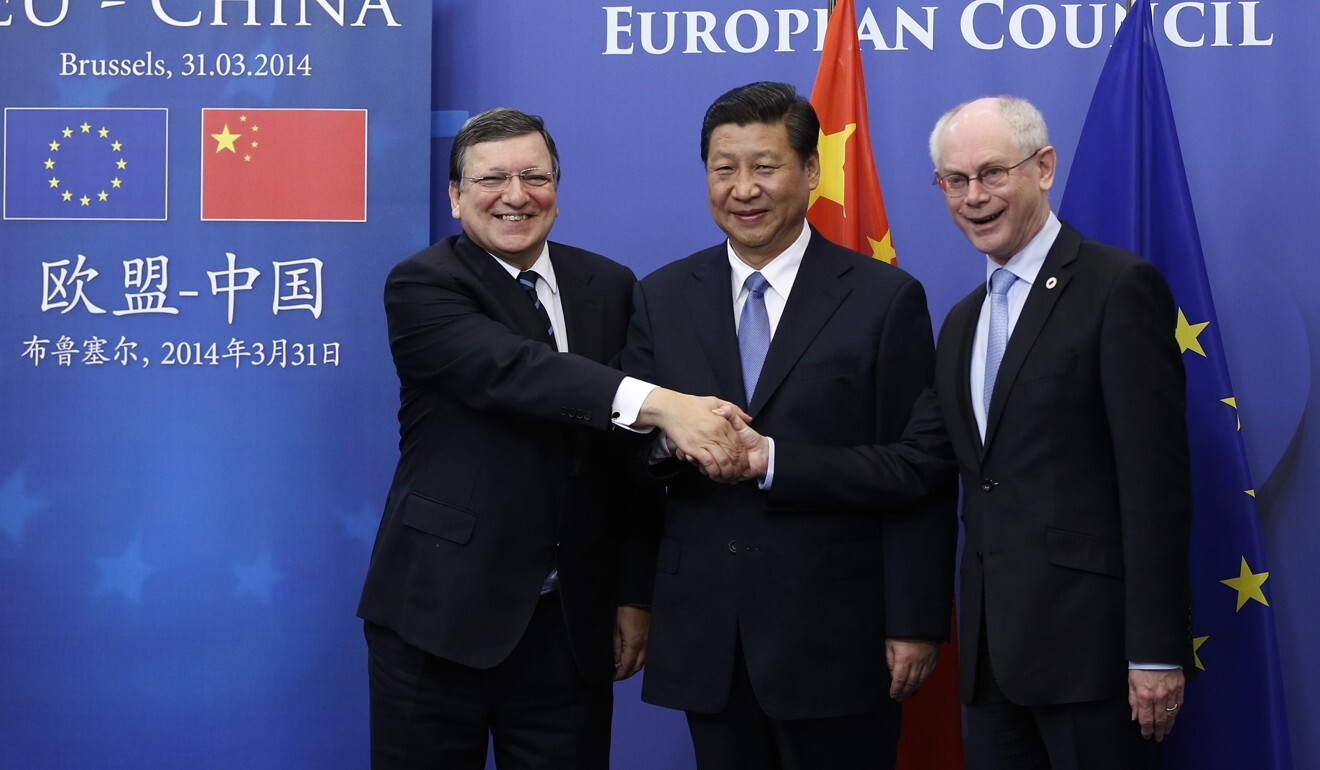

The EU first proposed the investment pact in 2012 and the two sides officially began talks in January 2014. It will replace 26 existing investment treaties between China and 27 EU member states.

The process of negotiations was non-transparent and it seems that member states do not exactly know what is inside the deal

According to Justyna Szczudlik, a China specialist and head of the Asia-Pacific programme at the Polish Institute of International Affairs, the talks were largely driven by big EU economies, especially France and Germany that are “overdependent on Chinese market” and would benefit the most from the deal.

Smaller European countries that do not have vast economic interests in the Chinese market had largely been left out in the cold, she said.

“The process of negotiations was non-transparent and it seems that member states do not exactly know what is inside the deal.”

Szczudlik described the deal-making as China’s diplomatic masterpiece. “The real winner is China, not the EU, even if the commitments/concessions that China promised would be eventually achieved,” she said.

“Unexpected China-led progress on the CAI that appeared in mid-December had political background, which was to show China’s power to undermine EU’s recently sharpened policy towards China and avoid transatlantic cooperation on China, bearing in mind upcoming Biden administration which is ready to strengthen ties with the EU,” she said.

Shi Yinhong, a professor on international relations with Renmin University in Beijing, said it remained to be seen what China would get from the deal or offer the EU.

“China has strong demand to access the investment markets of advanced economies amid the Sino-US hi-tech decoupling. Compromises on the demand or a delay to raise the demand would hit its own interests,” he said.

Under the deal, China has committed to pursue the ratification of international covenants on forced labour, which was reportedly one of the last stumbling blocks in the talks. European officials, including European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, however hailed Beijing’s promise to “make continued and sustained efforts” to ratify the International Labour Organization (ILO)’s convention on forced labour as a breakthrough and an “unprecedented outcome”.

China and the US are among the nine of 187 ILO member countries that have yet to ratify the treaty. Luft said the EU-China deal also posed an image problem for the US, when Washington was leading a global campaign against forced labour in Xinjiang and Tibet.

“This diminishes US moral authority to lecture Beijing, let alone the rest of the world, about labour practices,” he said.

China-EU investment deal: Beijing relents on human rights but will it shift on trade unions?

Philippe Le Corre, a non-resident fellow in the Europe and Asia programmes at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington, was also sceptical about China’s promises.

“I doubt China will ever comply with ILO conventions but the EU signed a trade deal with countries such as Vietnam where it tried to push them to adopt them. Nothing compulsory there,” he said.

Luft said against the backdrop of Brexit, Europe was “not exactly a paragon of compliance”.

While China’s record of delivering on its commitments was checkered, “both sides will have to hold each other’s feet to the fire and insist on stricter implementation”, he said.

Additional reporting by Wendy Wu and Keegan Elmer