South Korea caught in the middle as China, US ‘whales’ face off

- Nation has a difficult balancing act as the two superpowers engage in increasingly hostile disputes in its backyard

- Seoul is hoping Xi Jinping’s state visit will improve ties, while questions have been raised over the future relationship with Washington

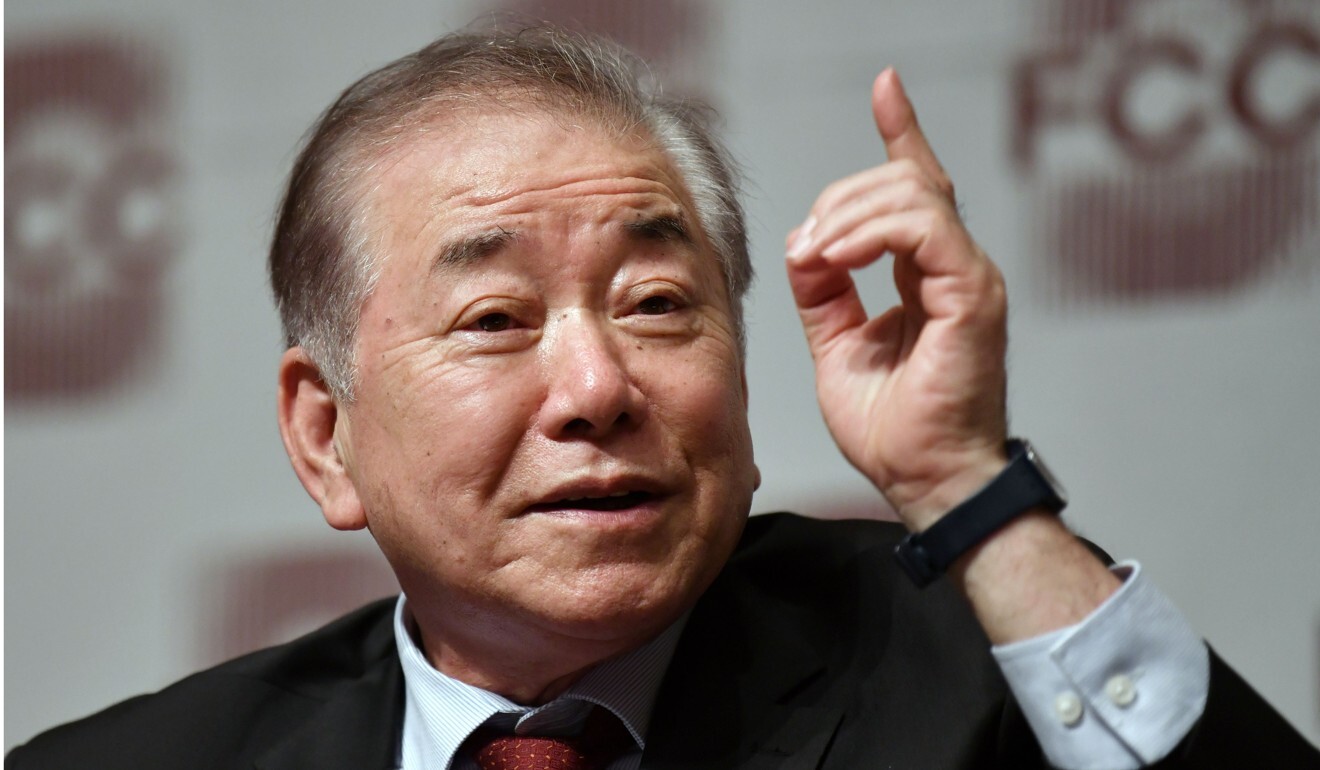

The country ranks in and around the global top 10 in gross domestic product and defence spending, said Kim Joon-hyung, chancellor of the Korea National Diplomatic Academy (KNDA) in the capital Seoul.

“We are not small and weak, but [we are] surrounded by these four superpowers geopolitically and geographically,” said Kim in a November 20 webinar hosted by the US-based George Washington University Institute of Korean Studies.

Two of the biggest whales – the US and China – are now circling each other in Korea’s backyard in increasingly belligerent disputes over trade, political influence, and what Washington calls a threat to the rules-based world order from China’s Communist Party.

With South Korea home to US military firepower and troops, yet having China as its biggest trading partner, the nation has to find ways to negotiate survival in a world upended by a pandemic, an emboldened Beijing, and a new US administration coming into office. Not to mention the perennial threat from North Korea.

Australia – not

Seoul’s approach can be contrasted with that of Australia, another democracy and mid-ranked power heavily reliant on trade with China, though in an entirely different geographical backyard.

Prime Minister Scott Morrison’s government has drawn Beijing’s anger and trade punishment for siding with the US on several issues. They include calling for an international investigation into the cause of the coronavirus pandemic first identified in China and protesting the arrest of pro-democracy lawmakers and activists in Hong Kong.

Australia needs South Korea, but Kim Jong-un and China are in the way

South Korea has sent clear signals to Washington it will not follow in Australia’s footsteps.

Adviser Moon, a professor of political science at Yonsei University, said joining a US-led front against China would bring conflicts into South Korea’s maritime backyard.

He argued that Washington would demand an end to South Korea’s policy of neutrality on thorny issues in the region outside its own waters, such as the Taiwan Strait, the South China Sea and the East China Sea.

China’s response would be “aggressive military moves in the Yellow Sea” on South Korea’s west coast, he wrote, adding, “Most sensible Koreans wouldn’t want Korea to be entangled in a sharp military conflict between the US and China.”

Joe’s view

The security ties between Washington and Seoul were born of the Korean war (1950-53), when South Korean and American-led coalition troops fought against China and North Korea for control of the peninsula.

But now questions are being raised about the future of US relations in the process of resisting Washington’s alliance-building against China.

Just because South Korea chose the US 70 years ago doesn’t mean it must choose the US for the next 70 years

On the 70th anniversary of the Korean war, Lee Soo-hyuck, South Korea’s ambassador to the US, said justifying the relationship based on a war that happened seven decades ago made no sense. He added that national interests should dictate Seoul’s relationship with Washington.

“Just because South Korea chose the US 70 years ago doesn’t mean it must choose the US for the next 70 years,” Lee said on October 12 during a meeting of the Foreign Affairs and Unification Committee, a South Korean parliamentary body.

His comments drew a strong backlash from South Korea’s conservative opposition party. Foreign Minister Kang Kyung-wha responded in a parliamentary hearing that Lee’s remarks were “improper”.

The ambassador’s seemingly maverick statement came at a time when South Korea, like many traditional US allies, is eager for new leadership in the White House.

For the past four years, the relationship has been hampered by US President Donald Trump’s demand that Seoul cough up an extra US$5 billion every year towards the cost of stationing American troops in the South.

Missile lesson

Meanwhile, the Moon administration is hoping Xi’s impending state visit will iron out any wrinkles left by the anti-missile dispute four years ago.

Even though Seoul argued that installing THAAD – Terminal High Altitude Area Defence – was to counter the missile and nuclear threat from North Korea, Beijing said the system’s powerful radar capabilities could be used to spy on China.

If we take sides with the US in an overt manner … then China will use the North Korea card

China’s government initiated a raft of boycotts on South Korean consumer goods. K-pop artists had their China visa applications denied while Korean television shows and music were blocked from streaming services. Tourism between the countries plunged.

00:53

South Korea deploys THAAD amid protests

In an interview with the South China Morning Post, government adviser Moon said Seoul needed better relations with Beijing because of the threat from North Korea. Moon was one of the architects of the so-called Sunshine Policy that called for engagement with North Korea as opposed to sanctions or other more aggressive tactics.

China is North Korea’s biggest trading partner over the 1,400km (870-mile) land border the two share. China is the only country with a legally binding mutual aid and cooperation treaty with North Korea, giving it leverage and influence over Pyongyang.

“If we take sides with the US in an overt manner, like allowing additional deployment of THAAD or allowing American intermediate-range missiles in South Korea … then China will use the North Korea card,” Moon said.

The Seoul-based adviser, who met Wang in November, added that there was a “mutual understanding” between Beijing and Seoul that there would be no additional deployment of THAAD.

Soured on China

But other members of Seoul’s foreign policy establishment say they do not see South Korea-China relations rewinding to their pre-THAAD state.

The entire episode “devastated” domestic sentiment towards China, as well as exposing the “vulnerability” of depending on China for trade, KNDA chancellor Kim said in the webinar.

According to state news agency Yonhap, Kim at KNDA – which trains South Korea’s diplomats – is an architect of Moon’s foreign policy. This includes the New Southern Policy aimed at deepening ties with India and Southeast Asian nations.

“Because of the THAAD incident, many Korean government officials and businessmen really rethought their commitment to China, some people tried to decouple,” he said. “[Chinese government officials] push South Korea too much, that makes Korea more inclined to the US. I’m not saying that’s the [South Korean] government position on China, but many people talked about that.”

However, Kim criticised what he called a “really irresponsible and unrealistic” line of argument among South Korea’s conservative politicians; namely that the country should completely decouple from China because its security (guaranteed by the US) comes before the economy.

“We are not a dictatorship or an authoritarian country, we cannot order businesses to come out [of China],” he said. “It takes time.”