Vaccine diplomacy strengthens China’s stature in Latin America, US congressional panel hears

- ‘The Chinese have made every delivery to an airport tarmac a photo op,’ one expert tells the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission

- Vaccine delivery, which has built on other outreach by Beijing including the Belt and Road Initiative, is said to weaken US influence in the region

The US-China Economic and Security Review Commission (USCC), which monitors the national security implications of Washington’s relationship with China, was warned that the US needed to start sending its highly successful vaccines to countries in the western hemisphere – and at the same time, to step up other diplomacy and development efforts to win back the hearts and minds of America’s neighbours.

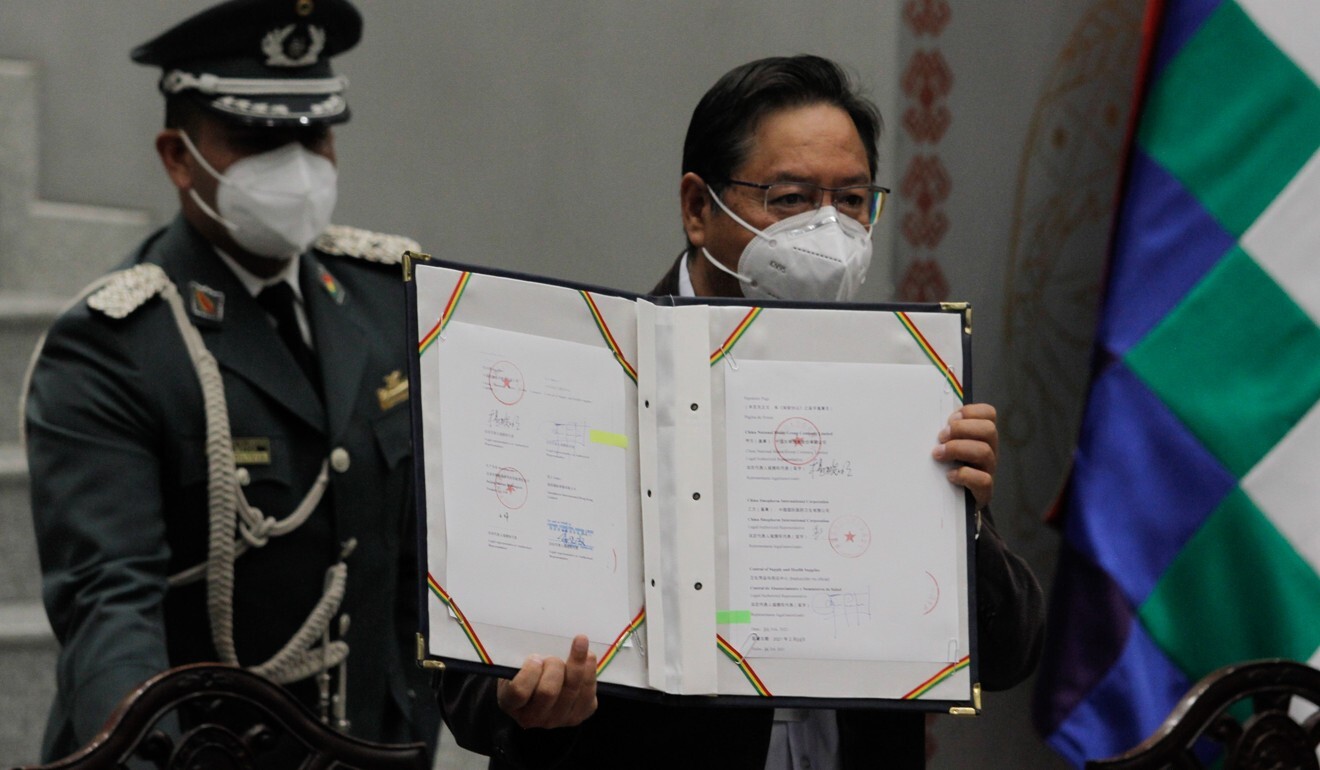

“The Chinese have made every delivery to an airport tarmac a photo op,” said R. Evan Ellis, a Latin American research professor at the US Army War College Strategic Studies Institute, told the panel. “The president comes out and the boxes roll off with Chinese flags on them.”

But the Chinese vaccines are far less effective than American ones, he added, leaving an opening for the US – if it decides to start shipping vaccines to the region.

Chinese President Xi Jinping to call for vaccine pledges at G20 health summit

“Chile was able to vaccinate 80 per cent of its population with the Chinese vaccine, yet the virus continued to spread,” Ellis said. “Something similar has happened in Colombia.”

According to Beijing-based Bridge Consulting, China has sold 651 million vaccine doses globally and donated 18.3 million so far.

The hearing came as Washington continues to regard Beijing’s global ambitions and rising assertiveness throughout the world with growing alarm.

That dynamic has increased dramatically during the pandemic, as China’s vaccine diplomacy has built on other outreach by Beijing to western hemisphere countries, including major infrastructure projects under China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The US has taken few meaningful actions in response while China sends medical supplies, builds dams and constructs highways across Latin America, the experts said.

China’s outreach efforts during the pandemic are indicative of its ability to move deftly in bolstering relations with Latin American countries via relatively small-scale initiatives, said Cynthia Watson, dean of faculty and academic programmes at the National War College.

In contrast, the US typically favours large-scale forms of statecraft – like treaties, which take longer to negotiate and culminate – Watson said, likening the US approach to filling a jar with rocks compared with China’s method of filling it with “grains of sand”.

“This is a part of the world that’s having a very hard time getting those vaccines from the major players,” Watson said. “They need to feel that we recognise they have human as well as geopolitical needs … And we haven’t been very effective at conveying that message, much less trying to replicate what I’ve described as China using all the sand to fill the jar.”

Other experts warned that China’s growing engagement in Latin American has led to the corruption of government officials and self-censorship in local media about issues Beijing considers sensitive. China’s exports of digital surveillance equipment have also given the region’s leaders new tools to control their populations, they said.

Brazil senators say anti-China views hurt country’s access to Covid-19 vaccines

The former Trump administration received some blame for creating a bigger US power vacuum in the region, in part by forcing countries to choose between staying close to Washington and getting closer to Beijing.

Another factor in Washington’s diminishing influence in the region is the hardening of rhetoric within US politics – largely from Republicans but also among Democrats – about immigration from Latin American countries, Watson added.

“This is the one part of the world where the United States ought to have its greatest benefit or ought to have its greatest ties,” said Watson. “But because of the growing anxiety in the United States about border crossings … as we focus on our concern about this region we’re not cultivating the ties that we have built.”

Francisco Urdinez, a political scientist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, noted that those ties had been fraying at least since 2001.

02:07

WHO chief slams ‘grotesque’ vaccine gap, asks producers to license technology to others

“The United States government should understand that its greater cultural and geographic proximity to Latin America and the Caribbean are not sufficient reasons to maintain its hegemonic influence over the region,” Urdinez said. “To retain part of the role it had before 2001, it should offer the public goods it once did.”

Those testifying were uncertain if that was possible now, in the face of Chinese financing and development projects in the region. They emphasised that those projects have appealed to governments across the political spectrum in Latin America.

“I hear a lot of folks say, here in DC and across the entire country, that Latin American nations – Latin American governments, leaders – would always prefer to work with the US if they could,” said Margaret Myers, director of the Asia and Latin America Programme at the Inter-American Dialogue think tank. “I’m not so convinced that that’s always the case anymore.”