China market still sluggish for Central and Eastern European goods

- Despite Beijing’s efforts to boost imports from countries in the 17+1 framework demand from Chinese consumers remains low

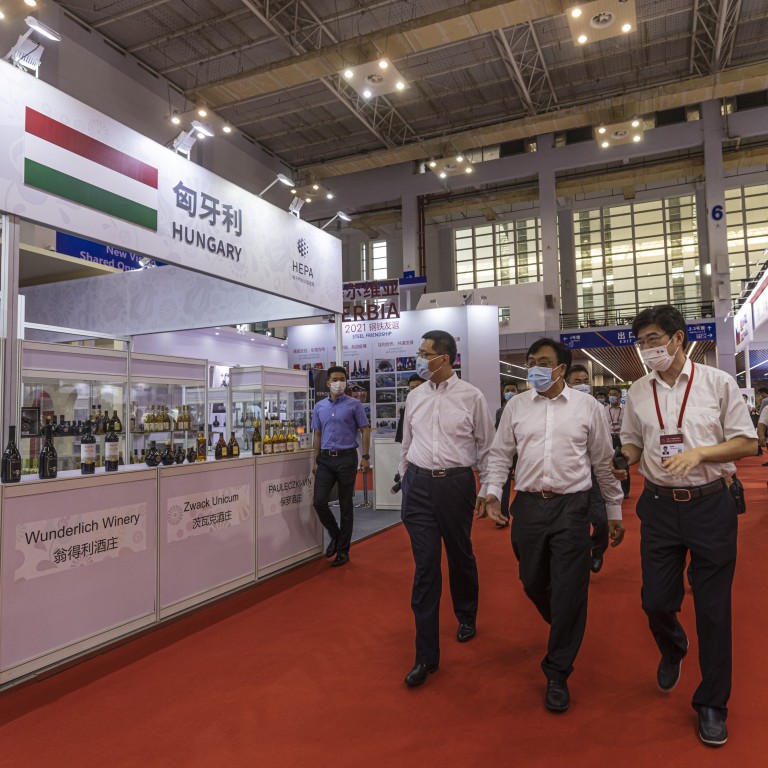

- A trade expo aimed at showing China’s commitment to the region fails to quell frustration over the slow rate of progress

“Once you have tried it, you will know how good it is,” the Chinese live stream host said repeatedly, as she promoted Bulgarian rose tea, Hungarian dessert wine and Latvian body scrubs to tens of thousands of customers in China watching on an e-commerce platform.

Not on show, however, was the frustration of some of these European countries at the difficulties in accessing the Chinese market, which officials and academics in China expect to continue, despite Beijing identifying market access as the key to boosting its relations with CEE countries.

Diana Mickeviciene, the Lithuanian ambassador to China, explained the decision, saying access to the Chinese market had not improved and the trade imbalance was only growing, nearly a decade after joining the framework.

The Baltic country was not the only one to voice frustration. Estonia, Latvia, Bulgaria, Romania and Slovenia, along with Lithuania, all sent lower-level envoys to President Xi Jinping’s annual 17+1 meeting in February – held virtually this year. It was a step largely understood to be snubbing the mechanism and expressing disappointment with working with China.

At the summit, Xi pledged that China would import more than US$170 billion worth of goods from the region in the next five years, doubling its purchases of agricultural products.

Lithuania quit 17+1 because access to Chinese market did not improve, its envoy says

However, at an academic conference held on the sidelines of last week’s trade expo, Wang Hongliang, the commerce ministry’s counsellor of European affairs, said the imports target was the most challenging of ways to improve ties with CEE countries.

“We will be talking to relevant and CEEC embassies, and we hope they can quickly provide a list of the names of the products that they can export [to China],” he said.

“We will also talk to relevant commerce chambers on how to move the plan forward. But the size of this imports target is really big. The work of the ministry or our relevant departments alone will not be enough, we will need a lot of parties to join the work.”

Wang was not the first to raise the difficulty. Foreign vice-minister Qin Gang said in a press conference after Xi’s announcement in February that CEE countries should strive to “increase their products’ competitiveness”. He also noted that China’s consumer market was a lucrative one for business.

While China has hailed a growth in trade with CEE countries of about 85 per cent in the nine years since the 17+1 framework was established, it has meant widening trade deficits for its Central and Eastern European partners.

As of 2018, the 17 countries’ total deficit with China stood at US$75 billion, according to a report published by the China Observers in Central and Eastern Europe – a group of scholars associated with Prague think tank the Association for International Affairs.

The Chinese government has not released comparable data, but Wang from the commerce ministry noted that, while the trade imbalance with the 17+1 countries was still increasing overall, some were thriving far more than others.

Among the CEE countries, Poland, Lithuania and Bulgaria sold the most agricultural products to China in 2020, according to Chinese customs, valued at US$250 million for Poland, and US$110 million for both Lithuania and Bulgaria. Data from 2019 showed imports from smaller countries like Slovakia, Albania and Macedonia stood at US$5 million.

Shang Yuhong, director of the Centre for CEE studies at Shanghai University of International Business and Economics, said the trade structure was difficult to change. “There is a big difference in competitiveness,” he said, pointing to China’s bigger exporting network in the region, which kept Chinese costs down, while CEE imports into China did not have a similar advantage.

He also said CEE products were not really suitable for the Chinese market, whereas China’s exports matched demand in the European region. “Chinese products are cheap and of good quality in the Central and Eastern European countries. In the reverse, CEE products are often not expensive but not cheap, there’s hardly any competitive advantage.”

For some of those working to boost CEE imports into China, bureaucracy is also a problem. Croatia’s Chamber of Economy representative in Shanghai Drazen Holmik said it had taken more than five years to get the necessary certification to import Croatian dairy products.

“[The process] is always slow and full of uncertainties,” Holmik said, adding that the dairy imports had finally started last year. “The numbers did go up but it’s not a lot yet. We also know we need to do more to compete in the Chinese market, it’s a big market.”