China tries to turn tables on West after criticism by UN Human Rights Council members

- Beijing says it is ‘concerned by the violations of the rights of refugees and migrants by countries such as the United States, the UK, Australia and Canada’

- UN sessions on migration and housing provide the latest battlegrounds for continued geopolitical sniping

China has attacked the United States, Australia, Canada and Britain over their records on migrants and refugees, continuing a blistering war of words with the West at the UN Human Rights Council this week.

Wednesday was the third day in which soaring geopolitical tensions spilled over into hearings, with sessions on migration and housing providing the latest battlegrounds.

A member of the Chinese mission to the UN said Beijing was “seriously concerned by the violations of the rights of refugees and migrants by countries such as the United States, the UK, Australia and Canada”.

“These countries kept migrants in prolonged detention in detention centres in poor conditions, lacking food, water, medical care and other basic services, resulting in large number of global deaths among migrants,” he said.

China criticised the US policy of separating children from their parents at the Mexican border, implemented by the Trump administration, saying: “Many children have been separated from and [are] losing contact with their parents and families, resulting in human tragedy.”

The session on migration was based on a report by the UN’s Special Rapporteur on the human rights of migrants, Felipe Gonzalez Morales, which focused on the impact of “pushbacks” of migrants on land and at sea.

Pushbacks are when refugees and migrants are forced back over a border – generally immediately after they crossed it – without any possibility to apply for asylum or argue against the measures taken.

Biden weighs ban on China’s solar material over Xinjiang forced labour

The report is highly critical of US pushback policy, including “Remain in Mexico” guidelines introduced in 2018, which requires asylum seekers seeking entry to return to Mexico while their claims are evaluated.

“The Special Rapporteur deplores the fact that migrants enrolled in the programme have faced kidnapping, rape, torture, murder and other violent attacks while forced to wait in Mexico,” read the report.

It also cited Australia’s policy of processing asylum seekers by sea in “offshore facilities in Papua New Guinea and Nauru, in circumstances and conditions that have had severe impacts on health, and particularly significantly [their] mental health”.

The Chinese delegation urged the UN to “pay continuous attention to the human rights violations in these detention centres around the world”.

01:11

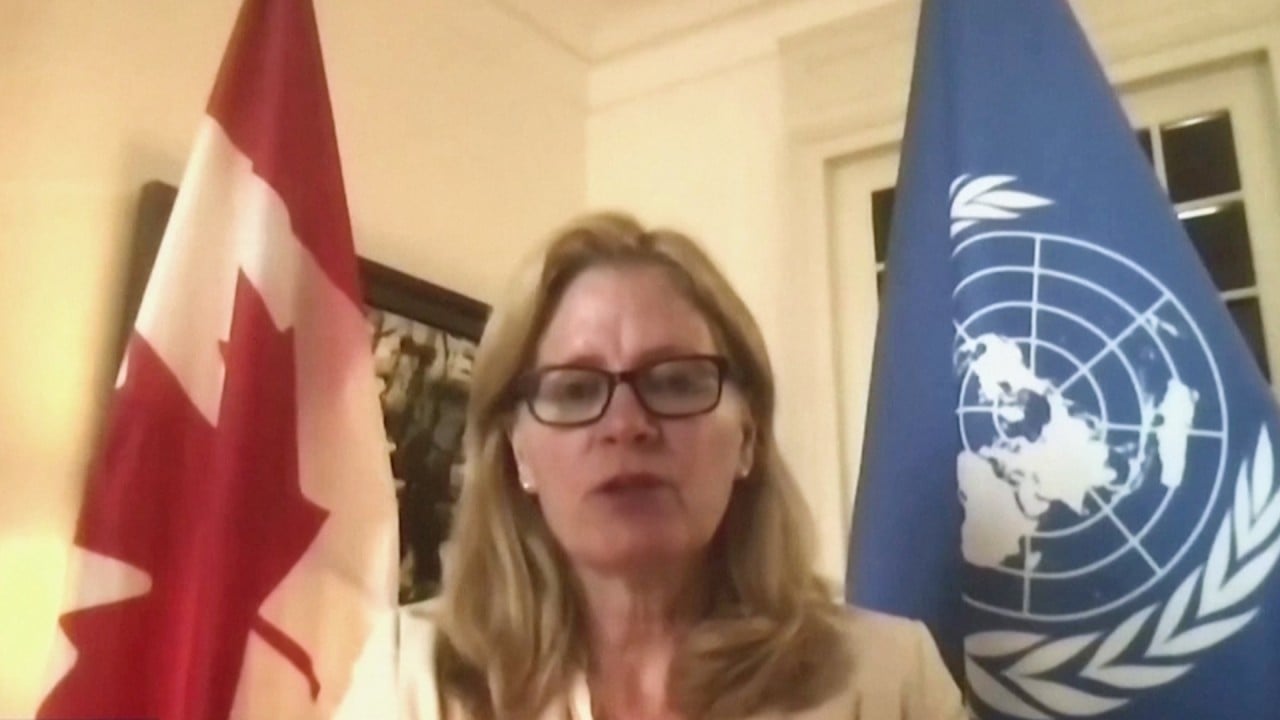

Canada leads call by more than 40 countries for China to give UN access to Xinjiang

Both Australia and the US have been engaged in intense geopolitical sparring with China over the past two years.

These disputes have spilled into multilateral forums, with the first three days of the UN Human Rights Council’s 47th regular session turned into open season by China and its political opponents.

Also on Wednesday, China criticised long-time rival Japan’s decision to discharge waste water from the Fukushima power plant nuclear disaster into the Pacific Ocean, saying the move was “entirely based on economic interests rather than on its impact on the marine environment, or safety and human health”.

Japan denied the charge – also levied by South Korea – saying it would “continue to provide accurate information to the international community in a sincere and highly transparent manner, based on scientific evidence”.

Is this the next Xinjiang product to upend global supply chains?

The statement urged “China to allow immediate, meaningful and unfettered access to Xinjiang for independent observers”.

On Monday, UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Michelle Bachelet said that she hoped to visit Xinjiang by the end of the year; China has yet to facilitate a UN inspection.

The mainly Western nations, with Japan the sole Asian signatory, also expressed “deep concern about the deterioration of fundamental freedoms in Hong Kong under the National Security Law and about the human rights situation in Tibet”.

China’s representative to the council issued a stern rebuke in advance of Tuesday’s statement, which was well telegraphed, accusing Canada and other signatories of “still enjoying their colonialist dreams”.

“They play the [role of] so-called ‘human rights masters’. However, they are provoking conflict everywhere and their own human rights records are really worrying. They have created racist conditions, and inequality are deep-rooted,” the Chinese representative said.

“Historically, Canada robbed the indigenous people of their land, killed them, and eradicated their culture,” he added.

This exchange sparked an angry response from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who said that “China is not recognising even that there is a problem”, while Canada is “on a journey of reconciliation”.

“That is a pretty fundamental difference, and that is why Canadians and people from around the world are speaking up for people like the Uygurs who find themselves voiceless, faced with a government that will not recognise what’s happening to them,” he said.

This session of the UN Human Rights Council is set to run until July 13.