Why Biden’s Afghan debacle 20 years after 9/11 gives China cause for worry

- Chaotic US withdrawal from Kabul has been greeted with great rejoicing by China’s state media and net users

- However, this is no post-9/11 era when the US was distracted by its war on terror. Now, it is free to focus on its current main adversary – China

00:52

Taliban fighters show off captured military hardware in the Afghan city of Kandahar

01:19

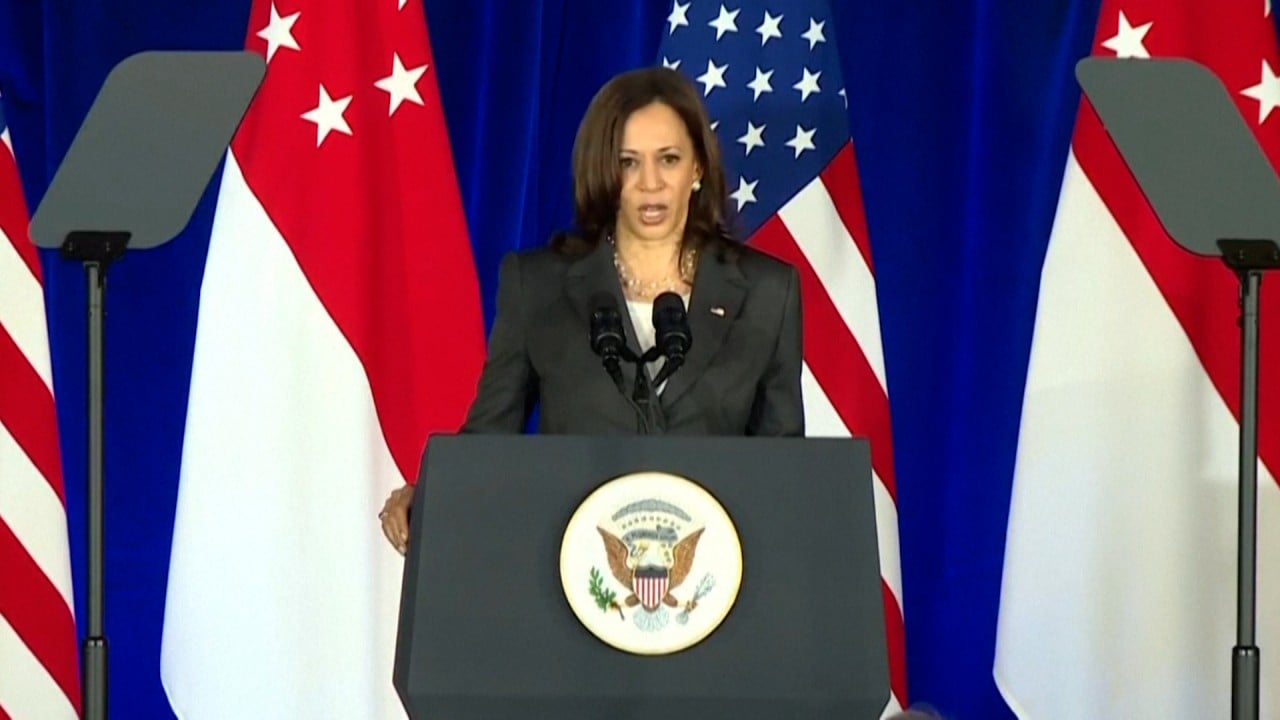

US Vice-President Kamala Harris: China continues to ‘coerce’ and ‘intimidate’ in South China Sea

Twenty years ago, the tragedy of 9/11 changed the course of history and became a turning point in bilateral ties, when US president George W. Bush was forced to put aside his hardline anti-China agenda in exchange for Beijing’s support in America’s war on terror.

Two decades after 9/11, China is more concerned than ever about Afghanistan

American strategists have since lamented the lost opportunity to keep China down. They say the 9/11 attacks amounted to a godsend for Beijing – a distraction for the US that, in Chinese diplomatic language, allowed a prolonged “period of strategic opportunities for the country’s development”.

They nonetheless agree with Chinese observers that 9/11 helped avert a premature US-China collision and ushered in a decade of relations warmer than anything the rival powers had ever experienced.

Reorienting America’s grand strategy from terrorism to the great power competition with China, its top adversary, has “the advantage of focusing on major threats to America’s security, economy, and values,” according to Harvard professor Joseph Nye.

01:50

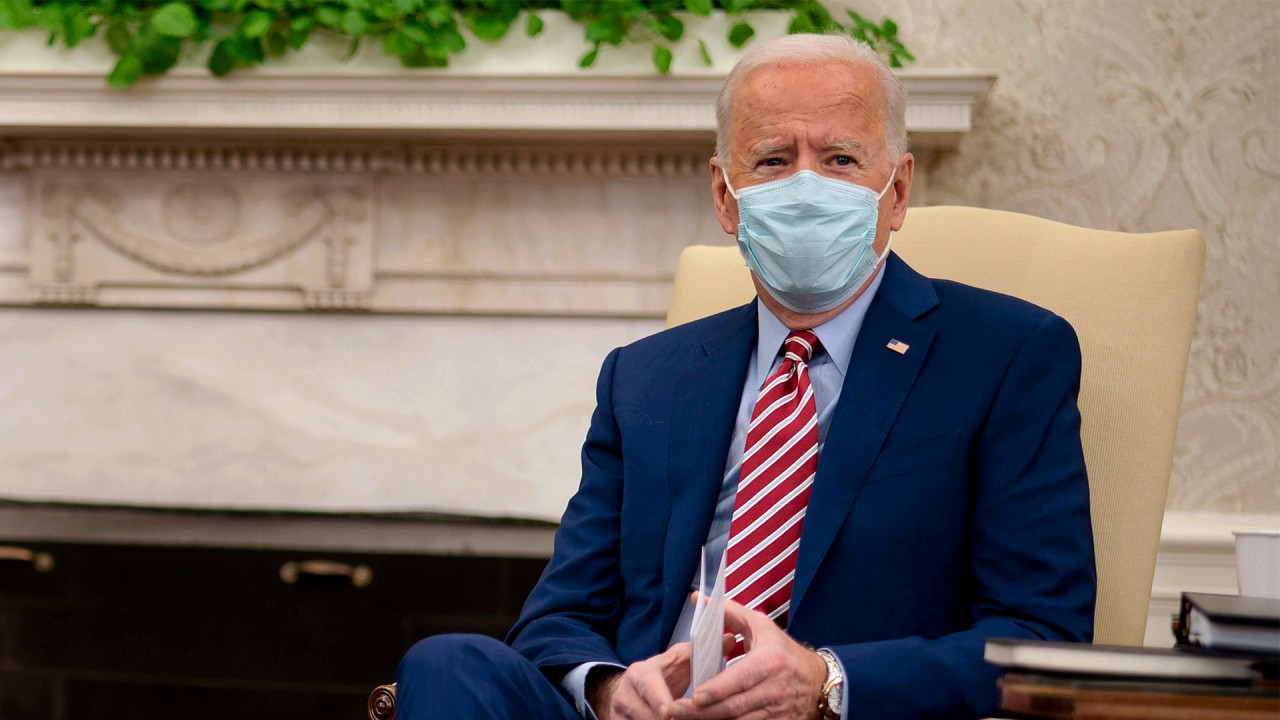

Joe Biden says China will ‘eat our lunch’ on infrastructure

Equally importantly, the Taliban remains largely a wild card, as it is too early to tell if and how the militant group would honour its pledges about cutting ties with its pro-terror past and ensuring stability in war-torn Afghanistan.