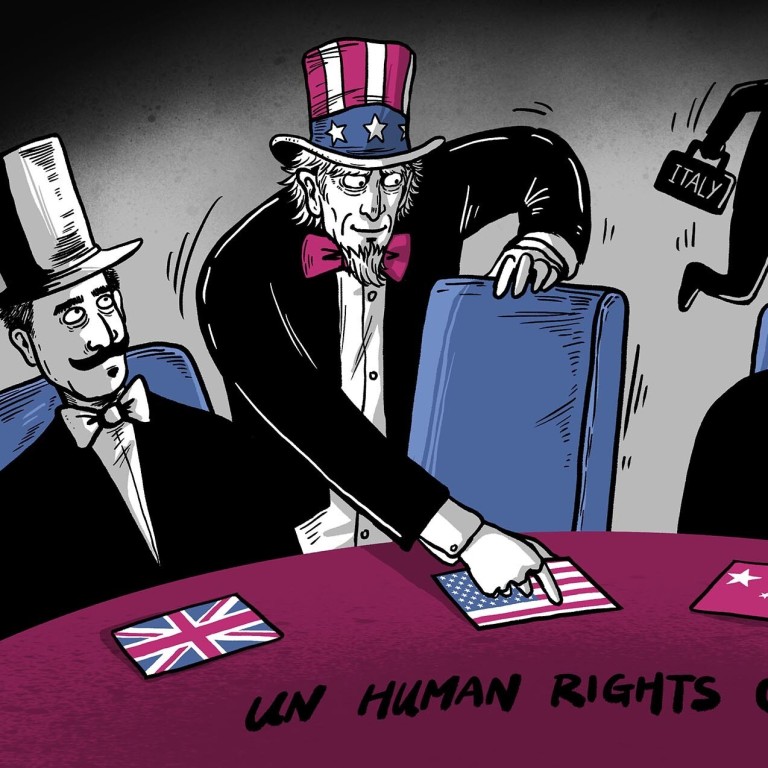

As US returns to the UN Human Rights Council, it confronts an increasingly forceful China

- A great deal has changed in the 3 years since the US withdrew from the council: ‘China is now the biggest player in town’, notes one diplomatic analyst

- Checking Beijing’s efforts to reshape the UN will take more than just coming back, as China continues to leverage its growing influence

“A huge amount is at stake,” said Marc Limon, executive director of Universal Rights Group, a Geneva-based think tank. “The world’s most important democracy needs to be there.”

But Washington faces risks, added Limon, a former British diplomat at the council from 2006 to 2012. “China is now the biggest player in town, has exploited the vacuum, upped their game and introduced a lot of initiatives to try and give a Chinese flavour to things.”

The US left the council in 2018 under former president Donald Trump, a vocal sceptic of multilateral organisations. The Biden administration has prioritised returning, arguing that democracies must confront authoritarian states at the UN and elsewhere in concert with partners and allies.

In theory, nations on the 47-seat Geneva-based council are elected. In reality, seats are often determined in advance within geographical blocs, frequently involving “back room deals, closed slates, and secret ballots”, according to a Brookings Institution report. The 18 seats up for election on Wednesday are uncontested, and Italy has relinquished its seat for the US.

Watchdog groups argue that more choice would expand transparency on the council. “We believe there should be a competitive election,” said Madeleine Sinclair, New York co-director of the International Service for Human Rights, “to discourage the idea that the game is rigged”.

But checking Chinese efforts to reshape the UN will take more than being in the room, as the Asian giant continues to refine its strategy and leverage its growing influence.

Under President Xi Jinping, however, Beijing has shifted more to offence, increasing the number and quality of its diplomats, and raising its UN financial contributions. Well-staffed missions in New York and Geneva now routinely attend even obscure human rights meetings, gathering intelligence and pushing back on initiatives deemed detrimental to China’s image or interests.

China pushes back against Xinjiang criticism in event hosted by its UN delegation

China has also become increasingly adept at introducing seemingly innocuous phrases, critics said, such as “cooperation” and “shared values”, into UN documents in a bid to shift, blur or supplant traditional definitions of human rights.

While “cooperation” sounds harmless enough, China is crafting a body of language supporting its view that “universal” individual human rights are not universal and that collectivism, state-directed authority, development and security are at least as important, they added.

Thus China’s July council resolution on “people-centred” development built on its June 2020 “mutually beneficial cooperation” resolution and a 2018 “win-win” resolution, they noted.

“Only with greater development can human rights be better promoted,” said Chen Xu, China’s ambassador in Geneva, said in July.

Civic groups term it an effective strategy. “They are incredibly good at building their own precedent, using turns of phrase that hearken back to their propaganda,” said Sarah Brooks, a former US diplomat who is now a Geneva-based programme manager with International Service for Human Rights. “It’s hard to get people riled up about language of UN resolutions. It’s not sexy. I’ve tried.”

UN experts said that Washington’s return to the council offers a welcome counterweight. But a great deal will depend on how the US uses its seat, they added

The Obama administration won praise for confronting alleged Chinese and Russian abuses even as it broadened the council’s mandate to include LGBTQ rights, the environment and other issues.

So far, the Biden administration – which gained observer status on the council shortly after its inauguration in January – seems singularly focused on China, analysts said. This threatens to alienate small and middle powers Washington wants to woo; define US strategy more by what it stands against than what it stands for; and polarise the council, undercutting its effectiveness, they added.

The US also needs to adjust to a new normal, others said. Since its 2018 departure, European nations stepped up even as China grew more sophisticated, presenting new challenges for Washington.

“It’s not the same superpower it was,” said Hillel Neuer, executive director of Geneva-based UN Watch. “China has raised its game enormously.”

China has raised its game enormously

On other fronts, China is making increasingly effective use of the “like-minded group” – a shifting voting bloc of more than two dozen largely authoritarian countries including Russia, Syria, Iran, Egypt and Belarus and others beholden to Beijing – to effectively block, deflect or drown out Western human rights initiatives and what China terms “name and shame” finger-pointing.

China is using the council and broader UN system to spread its thinking and more authoritarian values, said Richard Gowan, UN director for International Crisis Group. “Increasingly it’s a place where they can put through their own narrative, introduce resolutions on state-to-state cooperation and human rights as about development – none of that annoying individual human rights business.”

One result of China’s growing assertiveness, experts said: more duelling statements, tit-for-tat photo exhibits and contests, at times petty, to line up the most supporters on council initiatives.

In June, Canada delivered a US-backed joint statement on behalf of 44 nations expressing grave concerns over the treatment of “religious and ethnic minorities” in Xinjiang and deteriorating freedom in Tibet and Hong Kong.

A few days later, Beijing decried the US as a self-styled “human rights judge” and proudly announced that Belarus’s China-backed joint statement – that opposed interference in China’s internal affairs on the pretext of human rights – had won support from 65 countries.

In July 2020, a similar showdown saw 53 nations voice support for China’s imposition of a national security law in Hong Kong against 27 in opposition.

00:49

Hong Kong national security law has ‘chilling effect’ on freedoms, says UN human rights chief

“China will send cable to all posts in Africa saying ‘we have an initiative in the UN, you vote with us,’” a Geneva-based Western diplomat said. “If they get significant bilateral aid, that’s the default.”

Another effective Chinese tactic is what critics dub “whataboutism” – countering criticism of its human rights record with references to Israel’s treatment of Palestinians, US racism and the recent disclosures in Canada about the deaths of indigenous people, amplified by state media.

Washington, London and Ottawa are a “cartel of killers” hypocritically whipping up global “hysteria” about Xinjiang despite their own record of human rights violations, the Chinese tabloid Global Times said in June 2020.

“Beijing is saying, why are the US and Canada weighing in on indigenous rights when they have such a terrible record,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch. “But it creates an opportunity to do what Canada does, namely say, ‘we admit it, we’re investigating it, we’re not doing it any more, what about you?’”

China calls on rich nations to give more to UN, with apparent dig at US as ‘major’ defaulter

Limon, whose group tries to work with all sides, maintains that the deep US-China divide on the council was not inevitable. Toward the end of the Obama administration, Geneva-based Chinese envoys expressed genuine interest in engaging with the council, exploring women’s rights and other “soft” human rights issues where Beijing could contribute, he recalled, going so far as to plan an event and invite Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

Then the US delivered a statement roundly condemning China, Limon said, and the tide turned: “They figured, we tried the constructive approach, we were criticised anyway, so we might as well play hardball.

“And it’s gotten worse … They’re trying to reshape the council before the US gets back in.”

Many of the tools that China is wielding – organising alliances and leveraging aid, favours, obligation, threats and votes in support of resolutions or statements – have long been employed by the US and other superpowers.

But China has come on fast and strong, often effectively and unabashedly appealing to or pressuring developing countries. One example: a March 7, 2019, letter from its Geneva mission and obtained by Human Rights Watch that warns other countries not to participate or attend a US-sponsored event about Xinjiang “in the interest of our bilateral relations”.

China’s growing assertiveness dovetails with its expanded political, military and economic might and a more muscular leadership style by Xi. But it also reflects Beijing’s attempt to safeguard control by exporting core Chinese Communist Party beliefs globally, an analyst said. This, outlined in the party’s 2013 “Document 9”, identified seven “dangerous Western values’” – reportedly including democracy, civil society and human rights.

“China now feels that it can be stronger and more muscular, which you’re seeing in the human rights regime,” said Rana Siu Inboden, a senior security and law fellow at the University of Texas, Austin, and formerly with the US consulate in Shanghai. “You’re now seeing Document #9 play out as it tries to propagate internationally its domestic vision.”

But China has also made some missteps. Support for its 2020 re-election to the council amid crackdowns in Hong Kong and Xinjiang fell to 139 votes from 180 at its prior election – its lowest tally since the council’s formation in 2006.

“There’s more concern toward China, more questioning than five years ago,” said Ted Piccone, a Brookings foreign policy fellow. “In general, there’s a waking up to what China brings to the table, both good and bad.”

And in January during the council’s election for president, China strongly opposed the Fijian candidate, Nazhat Shameem Khan – who had a strong human rights record – mounting a late push for Bahrain.

Khan won handily, and Beijing’s opposition to a developing country and a small Pacific island candidate – two groups it has sought to court in facing off against the US over the South China Sea – was not a good UN look, some said.

As more nations grow wary of China’s muscular approach – recent polls show near-record distrust of China’s and Xi’s intentions among advanced economies and a sharply reduced belief that Beijing respects the personal freedom of its people – it has faced more resistance.

Last October, it quietly withdrew a council resolution calling for “people-centred approaches” to human rights – regarded by critics as a further effort to position human rights as something shaped by individual nations rather than as a universal value.

Since then, in a February speech to the council, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi argued that a “people-centred” approach would help redefine human rights. “Human rights are not a monopoly by a small number of countries, still less should they be used as a tool to pressure other countries and meddle in their internal affairs,” he said.

Analysts said they hope for less confrontation but are not holding their breath. “Everyone knows this is just a fight between the US and China. It’s as bad as I’ve ever seen it,” said Limon. “This is really destroying the council. It really needs leadership, I’m hoping for a more nuanced approach.”