Explainer | The US has practised ‘strategic ambiguity’ on Taiwan for decades. Is that set to change?

- Joe Biden’s confusing remarks on defending Taiwan militarily provoked a sharp rebuke from Beijing and a quick clarification from the White House

- Analyst sees subtle shift to ‘strategic clarification’ policy, where US officials send out contradictory signals as part of using Taiwan to counter Beijing

Welcome to the world of “strategic ambiguity”, the long-held position of Washington on issues related to Taiwan and the island’s relationship to mainland China.

Read on to find out what this policy entails.

Why has the US stuck to an ‘ambiguous’ Taiwan policy?

Washington’s policy is to be intentionally vague about whether it would come to Taiwan’s defence if Beijing attacked. This is meant to deter the mainland from taking action, without the US committing itself to war.

While having official diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China – meaning it recognises Beijing as the seat of the sole legal government of China – the US also supports a “strong unofficial relationship” with Taiwan, and has said it will not pressure Taiwan to settle with Beijing on the issue of sovereignty.

However, it has never formally defined the conditions of “arms of a defensive character”.

But the same year, when Taiwan asked for assurances on the US stance on cross-strait relations, Washington formally agreed to six key points – known as the “Six Assurances” – including that it would not set a date to completely cease arms sales to Taiwan, effectively leaving its promise to Beijing open-ended.

US policy towards the cross-strait issue thus far has been a careful balancing act, allowing it more flexibility in its policy towards Beijing and Taipei and benefiting from relationships with either side.

What are the pitfalls of strategic ambiguity?

The US stance has allowed it to support Taiwan’s autonomy without being accused of emboldening the island to push for independence, and without committing to participating in any armed conflict.

However, critics say this ambiguous position can also be easily misinterpreted, and the possibility that the US may come to Taiwan’s defence is no longer a strong deterrent towards a more assertive Beijing.

China hawks advocate a clearer US position to put pressure on Beijing and ensure the security of self-governed Taiwan – or the antithesis of strategic ambiguity, often referred to as “strategic clarity”.

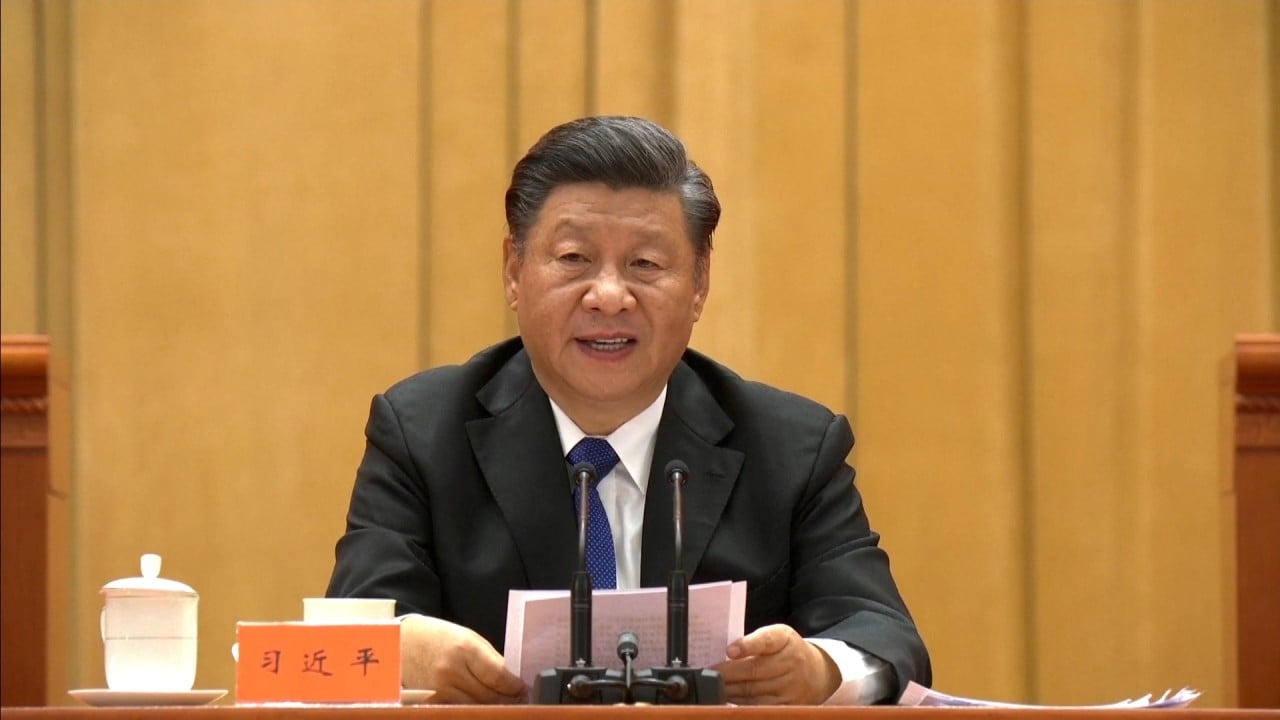

How Xi and Biden tackled hot-button issues at virtual summit

However, even those who want more clarity have major disagreements over what this should look like, with three main options being debated fiercely:

-

Conditional support where Washington will come to Taiwan’s aid if Beijing initiates a provocation

-

Withholding support if Taiwan launches unprovoked agitation

-

Unconditional commitment to support Taiwan in any scenario

“The ambiguity-versus-clarity debate superficially reflects the divergence among American politicians on how to form an ‘effective deterrence’ [to Beijing attacking Taipei]. But at a deeper level, it reflects that the United States is facing two intractable changes on the Taiwan issue,” Huang said.

“One is that the mainland is growing more capable of seeking national reunification with Taiwan. The other is an intensifying tendency that separatist forces on the island are trying to leverage Sino-US contradictions.”

Is strategic ambiguity on its last legs?

A sudden change in cross-strait relations will not help US strategic interests in the short run, so its goal of maintaining the status quo will not be fundamentally changed, Huang said.

He added that the Biden administration’s current stance suggests the US considers Beijing’s ambitions a greater risk than action from any separatist forces in Taiwan.

Washington appears to have subtly shifted to a policy of “strategic clarification”, which Huang said involved officials at different levels sending out contradictory signals on the US stance on cross-strait relations.

This included even using the excuse of “slips of the tongue” – to assure Taiwan of its support while later clarifying that Washington’s position that there was only one China had not changed – as it did after Biden’s comments.

Blinken says US and allies would ‘take action’ if Taiwan were attacked

“Such a move actually symbolises a warning signal to the People’s Republic of China, and could be a new type of ‘strategic ambiguity’ in the near future,” Huang said.

As mainland China gains power in East Asia, there may be more US consensus on the geopolitical strategy of using Taiwan to counter Beijing, he added.

“The frequency and degree of ‘strategic clarification’ may increase, which is bound to pose a strong but risky impulse for Taiwan independence forces.”