Advertisement

Nixon’s historic trip to China: how the landmark Shanghai Communique shaped ties for the next 50 years

- Joint statement released on last day of US president’s visit in 1972 is arguably the most important breakthrough agreement in the history of US-China relations

- Critics argue the visit and communique were the beginning of the US’ dilemma over Taiwan, especially surrounding its strategic ambiguity

Reading Time:8 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

1

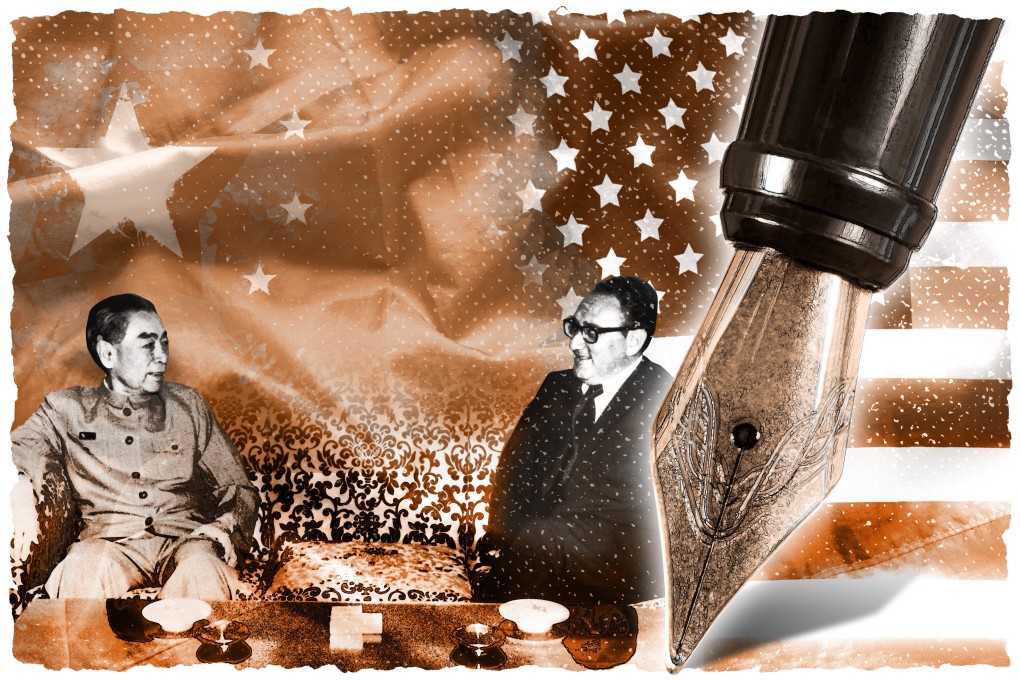

In February 1972, US president Richard Nixon defied conventional foreign policy wisdom when he arrived in Beijing for meetings with Chinese leader Mao Zedong. In recognition of the trip’s historical significance, the South China Morning Post is running a multimedia series exploring interesting points of the past 50 years in US-China relations. In the third piece in the series, Shi Jiangtao looks at the lasting implications of a document negotiated by top diplomats Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai.

When former American national security adviser Henry Kissinger returned to Beijing three months after his secret groundbreaking trip in July 1971, the real test had just begun for the Cold War rivals seeking rapprochement through dialogue.

Part of Kissinger’s mission was to hammer out the finer details of United States president Richard Nixon’s historic trip to China that both sides had agreed to in July, including setting the date and discussing press coverage to convince the hostile public in the US to warm towards communist China.

Advertisement

He was also tasked with an even more challenging job: to draft a joint statement for the presidential visit with then Chinese premier Zhou Enlai. The resulting document that was issued on the last day of Nixon’s China trip in February 1972, would become known as the Shanghai Communique. It is arguably the most important breakthrough agreement in the history of the US-China relations.

Kissinger’s second trip to China was different from the first exploratory visit which took many US allies and officials at Nixon’s White House by surprise with its strict secrecy. It was described as “a masterpiece of undercover work” by the late Harvard professor Roderick MacFarquhar.

Advertisement

Code-named “[Operation Marco] Polo II” and publicly announced weeks before Kissinger left for China, it was effectively a full-scale dress rehearsal for the historic presidential visit. Kissinger, who had just emerged from the glittering success of the first visit, also took Nixon’s Air Force One, the “Spirit of ’76”.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x