Guinea’s military rulers pressure Chinese and other foreign companies to pay more mining royalties

- About half of China’s imports of bauxite – a mineral used to make aluminium – are from the West African nation

- China sees Guinea’s Simandou iron ore deposit as a key source to help reduce its reliance on supplies from Australia

The ruling Guinean military junta’s determination to increase revenues from its bauxite and iron ore resources could hit China’s efforts to make inroads into the West African nation.

Chinese companies have vast investments in Guinea, which is the world’s second largest producer of bauxite, a mineral used to make aluminium. About half of China’s bauxite imports are from Guinea.

But Guinea’s military rulers have toughened their stance towards multinationals, saying they want the country to earn more from its mineral resources. Last week, the junta ordered mining companies to present proposals and a timetable for the construction of refineries to convert bauxite into alumina within Guinea by the end of May.

“Despite the mining boom in the bauxite sector, we have to admit that the expected revenues are below expectations, and you and we cannot continue this game of fools that perpetuates great inequality in our relations,” junta leader Mamady Doumbouya said in a meeting with stakeholders in Conakry.

Without providing specifics, Doumbouya warned that “penalties” would follow if the mining companies failed to meet the deadline. Bauxite miners have reportedly committed to developing refineries in the country, but not much has progressed.

Guinea coup adds to growing knots in China’s belt and road plans

Anthony Everiss, a senior aluminium analyst at the commodities consultancy CRU Group, said Guinean leaders had been seeking ways to turn the nation’s mineral wealth into a means of economic development.

He said the junta’s move comes at a time when Guinea’s bauxite shipments to China are at an all-time high, surpassing six million tonnes in a single month for the first time. However, there currently was just one alumina refinery in operation, and it was built several decades ago, Everiss said.

The announcement “is the first time Guinea’s junta has shown its hand and is the strongest sign of intent yet that [it] is determined to pursue its policy of resource nationalism”, Everiss said.

“Guinea is now much more aware of the value of their resources” and has better control of the mining industry and exports, he said.

CRU does not expect a greenfield alumina refinery to be built in Guinea before 2026. Technical limitations and higher capital costs in Guinea versus China may lead to disappointment in the government’s expectations, it said.

The consultancy estimates that six companies have planned 11 million tonnes per year of alumina refining capacity in Guinea. But unlike the significant progress in bauxite mining, movement on alumina refineries has been slow. Only the project by Société Minière de Boké (SMB) has made some progress; all others are in early stages.

Chinese firms including Chalco Guinea, Jinjiang Group Guinea, TBEA Guinea, Henan International Guinea and Zibo Rundi Guinea are in the early investment stage.

However, analysts say it is unclear if this would have an immediate impact.

“Presentation of plans would not automatically translate to aluminium production,” said W. Gyude Moore, a senior policy fellow with the Centre for Global Development and a former Liberian public works minister.

He said most African governments harboured ambitions of moving up the value chain of their mineral exports, so the junta’s announcement “is not surprising”.

Guinea signs US$15 billion deal for Simandou iron ore site

Bauxite is not the only resource for which Guinea wants more royalties. The junta said that work at the Simandou iron ore project, where operations were suspended last month, had not progressed and that it was not clear how the mine contributed to national interests.

The project has been hit by delays because of years of ownership disputes and slow progress on the 650km (400-mile) railway needed to transport the ore to Guinean ports.

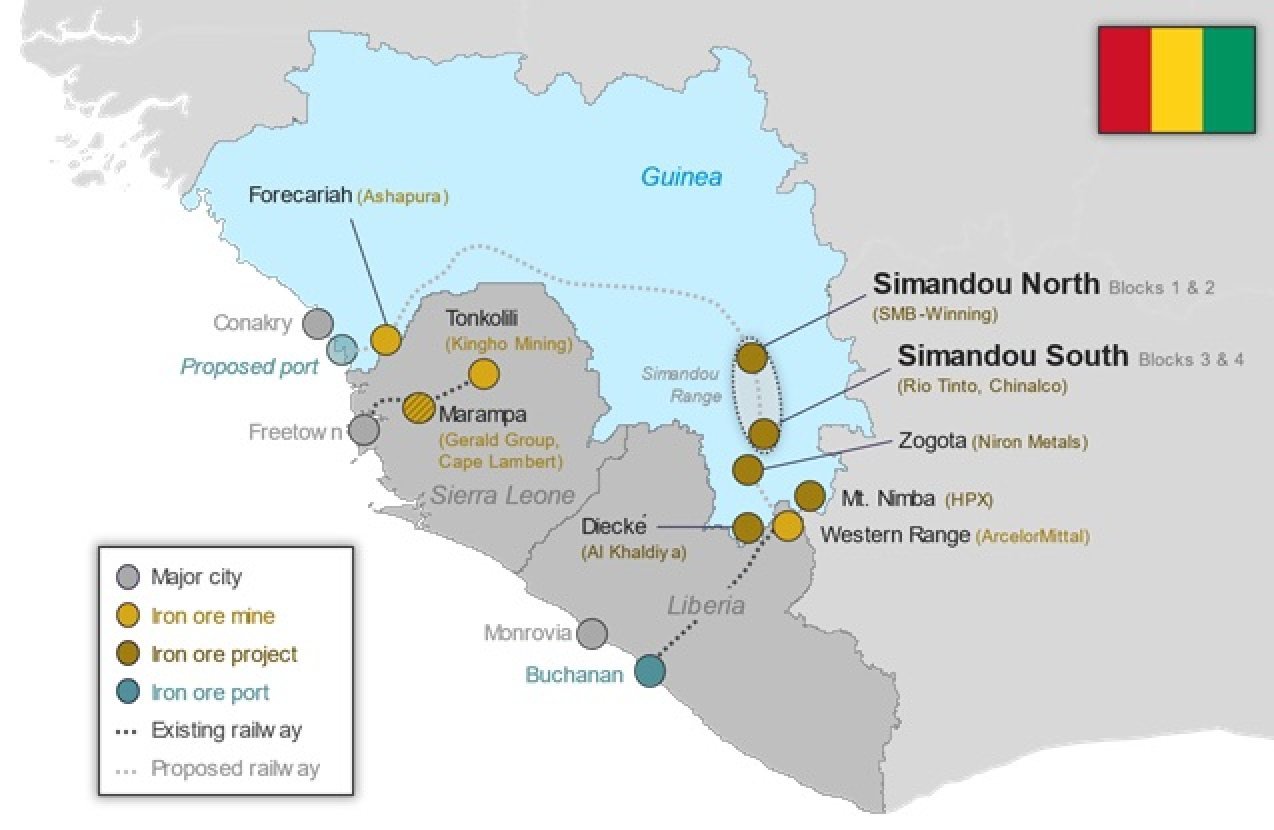

Simandou is divided into four blocks with an estimated 2 billion tonnes in commercial-scale, high-grade reserves.

Anglo-Australian multinational Rio Tinto owns 45 per cent of Blocks 3 and 4; Aluminum Corp of China, or Chinalco, holds 40 per cent; and Guinea’s government has the remaining 15 per cent. Blocks 1 and 2 were awarded in 2019 to SMB, a consortium formed by Singaporean shipowner Winning Shipping, Chinese aluminium producer Shandong Weiqiao, the Yantai Port Group and the Guinean transport and logistics company United Mining Supply.

Australia supplies about 60 per cent of China’s iron ore imports, but ties between the two countries have been strained since Canberra called for an international investigation into the origin of the coronavirus and banned China’s Huawei Technologies from its 5G network.

That dependence has been driven home in recent weeks with sanctions on Russia driving up the price of commodities, including Australian iron ore.

Lauren A. Johnston, a visiting senior lecturer at the University of Adelaide, said the Guinean leaders were “simply taking advantage of contemporary global tensions and supply chain fears to get a better deal for Guinea”.

“Remember that countries like Morocco are gaining aspects of supply chain production that is moving from Ukraine. I guess Guineans also want to join the upgrade opportunism, as much as nationalism strictly. I think they are just thinking it’s a good time to go for a marginally better deal for them,” Johnston said.

She said Chinese companies had always been relatively happy to move in the direction of local industrialisation.

“This may be less true in terms of minerals processing – they have such scale at home it would be hard to compete,” Johnston said.