China slashes African infrastructure loans but ICT funding holds firm

- Data shows 11 deals worth US$1.9 billion were signed in eight countries in 2020, a 78 per cent drop on the previous year

- Analysts say effects of Covid-19 on African economies and a worldwide pullback of China’s lending could explain the shortfall

According to the Chinese loans to Africa database, managed by the Boston University Global Development Policy Centre, this compares with 33 loan agreements worth US$8.3 billion in 2019.

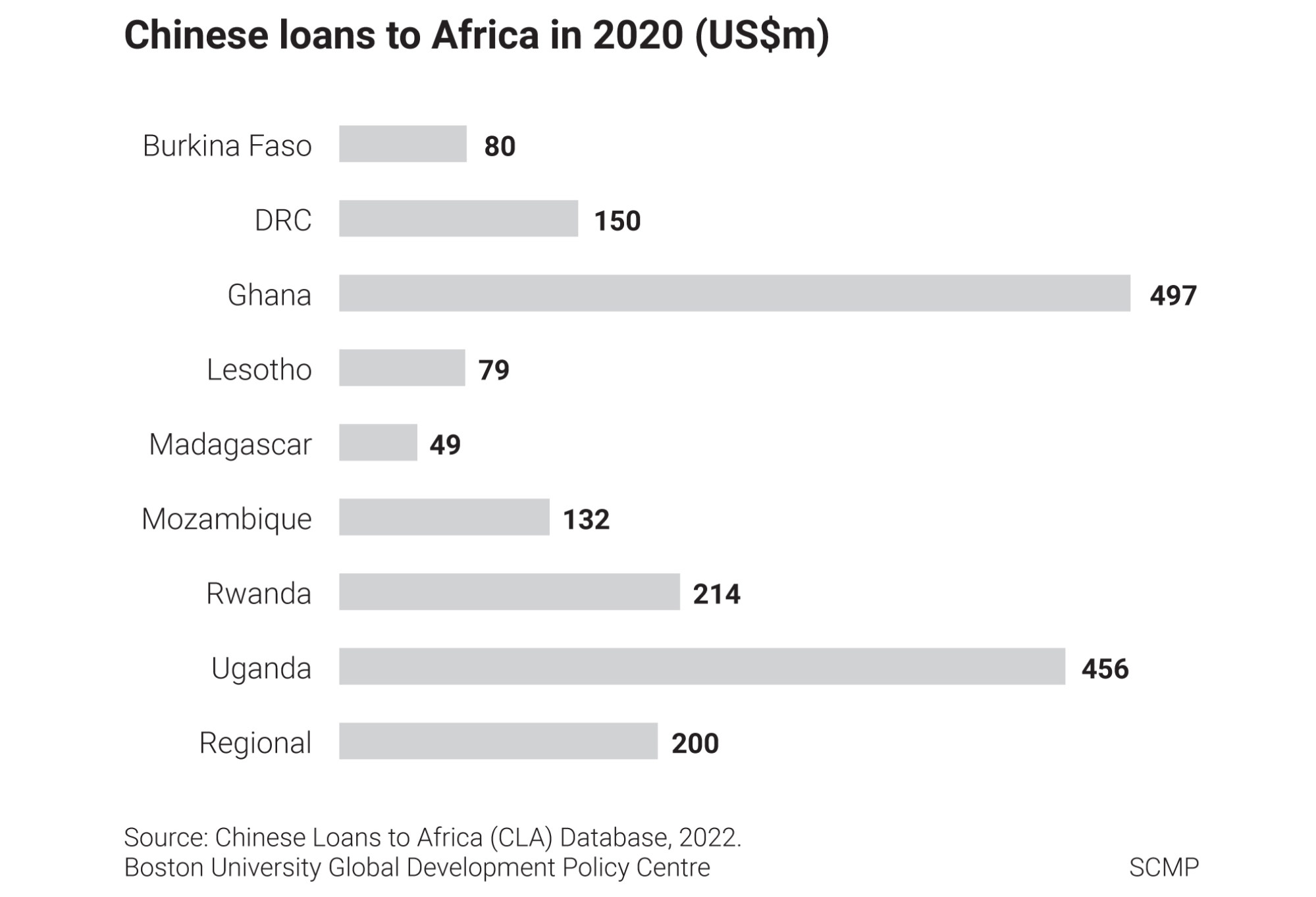

The 2020 agreements included transport, power, ICT and banking sector projects in eight countries – Burkina Faso, Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique, Rwanda and Uganda, the centre’s researchers said in a study released on Monday.

China Eximbank financed eight of the projects, with the remainder going to Bank of China, Industrial and Commercial Bank of China and Dongfang Electric International Corporation.

Notably absent from the list of lenders was China Development Bank, with no new loans in 2020, after its years of shrinking African investments in relative and absolute terms since 2016.

The regional African Export-Import Bank, based in Egypt, received US$200 million from the Bank of China to support the recently launched pandemic relief fund.

Global China research fellow Jyhjong Hwang, who led the research team, said the reduction in loan commitments “is a continuation of a long-term decrease since 2016 and further exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic”.

In the latest briefing from the Global Development Policy Centre, Hwang said the effects of the pandemic on African economies and a worldwide pullback of China’s lending could explain the drastic drop in financing.

Heightened default risks from ballooning public debt might have dampened China’s appetite for more lending to Africa, with Zambia becoming the first African state to default on its Eurobond repayments in November 2020, she added.

“The Covid-19 pandemic likely impacted both African countries’ ability to borrow and China’s willingness to lend.”

The researchers noted that one sector had avoided a hit from the pandemic, with the database showing an increase in loans to the information and communications technology industry in 2020.

Nigeria looks to Europe as Chinese lenders move away from costly projects

After years of trailing the transport, power and mining sectors, ICT accounted for US$568 million worth of loans across five projects to take second place after transport – an amount broadly consistent with its 20-year average of US$640 million each year.

In contrast, transport and the power sector suffered precipitous cuts to lending in 2020, after a decade of average annual loan commitments of US$2.3 billion and US$1.9 billion, respectively.

“While ICT projects with loans signed in 2020 will not materialise immediately, the acute need for communication abilities was likely amplified during the pandemic,” the researchers said.

They also noted that the reduced lending to the power sector might be part of a larger trend, marking China’s retreat from financing coal and hydropower projects, which have been controversial.

Data analyst Oyintarelado Moses from the policy centre’s Global China Initiative, said the pandemic had “significantly constrained” many African borrowers and intensified the “cautionary” practices of Chinese lenders in recent years.

“Looking forward to the post-pandemic era, Africa’s development-related financing gaps and the constrained debt environment of some countries will necessitate Chinese lenders to find innovative ways to partner with African governments to support infrastructure development and reach sustainable development goals,” she said.

Despite the low volume of 2020 loan commitments, Chinese lending to Africa remains significant.

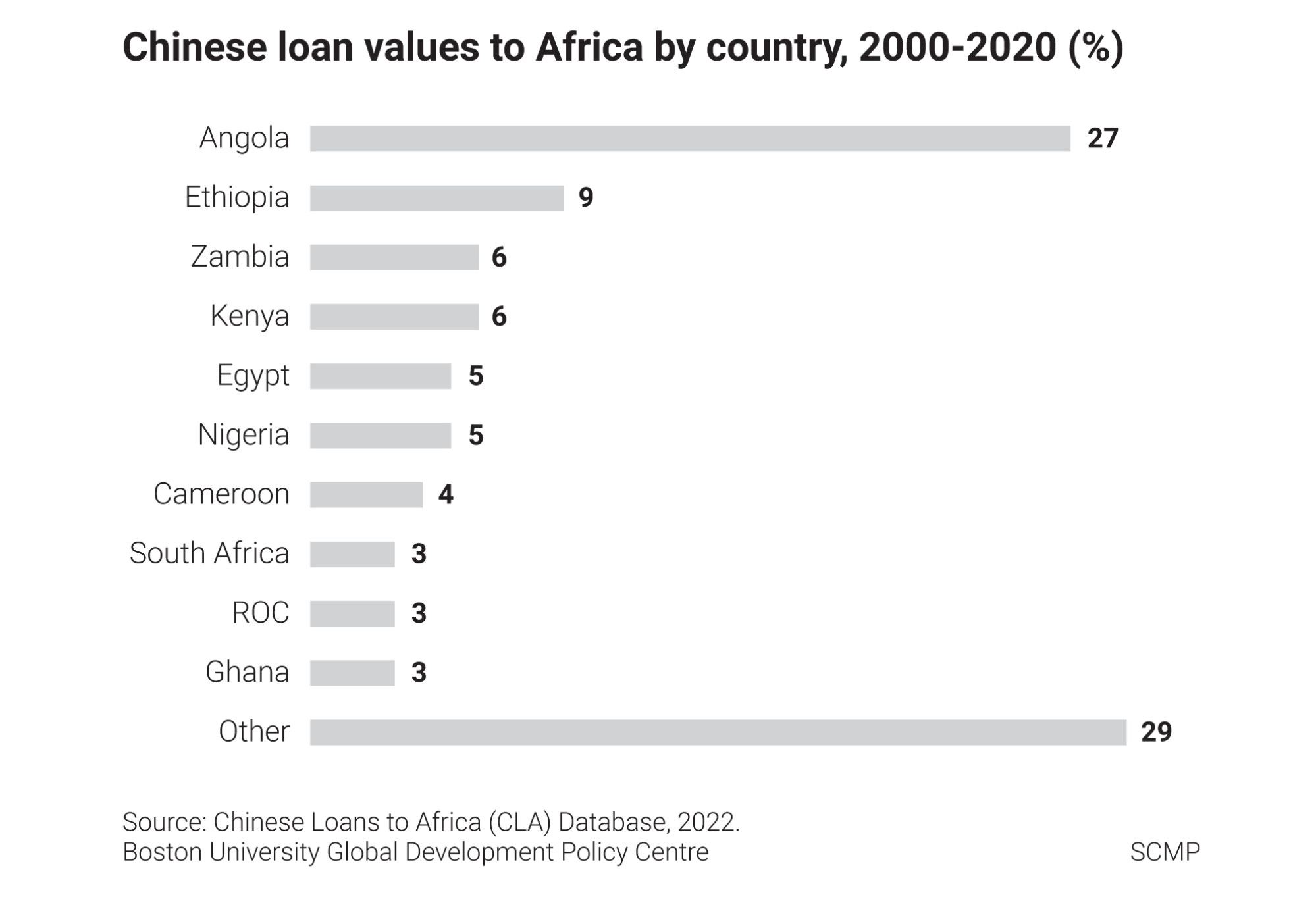

Between 2000 and 2020, the database recorded 1,188 loan deals worth US$160 billion to 49 governments, their state-owned entities and five regional multilateral organisations. The loan amounts are not equivalent to African government debt, as the database does not track disbursements or repayments.

Xi plays up roles for private sector in China-Africa trade and finance

Over the decade, 71 per cent of the loans went to 10 African countries – Angola, Ethiopia, Zambia, Kenya, Egypt, Nigeria, Cameroon, South Africa, Republic of Congo and Ghana.

Oil-rich Angola received the highest amount, accounting for 27 per cent of all Chinese loan commitments to the continent, with large oil-backed lending facilities from China Development Bank and China Eximbank.

While loan commitment levels might recover slightly, the researchers said that “without structural changes to borrowing practices and lending standards, loan amounts are unlikely to buck the long-term reduction trend”.

Other financing instruments – such as foreign direct investment or Chinese loans to African regional banks for on-lending to governments – might become more frequent sources of financing development projects in Africa, they noted.

“However, the extended decrease in loans since peaking in 2016 – or since 2013 when excluding Angola – poses uncertainty about Chinese lenders’ future appetite for providing high amounts of financing and African borrowers’ readiness to borrow more.”

The researchers said it might be “down now, but not out” since “a loan reduction in 2020 may not reflect a definite pullback of Chinese lending to the region, as the decline highlights how Chinese loan amounts tend to fluctuate during times of crisis and exposure to structural risk levels”.

China opens party school in Africa to teach its model to continent’s officials

Hwang noted that Chinese lenders had displayed more caution since 2016, when financial regulations were issued in China emphasising risk mitigation and control.

There might be also a reorientation under way of China’s investment policy towards increasing domestic demand, she said.

After close to two decades of countering overcapacity and expanding overseas markets through the “going-out” policy, the US-China tariff war of 2018 raised calls for a refocus on developing China’s domestic markets.

The pandemic hastened this inward turn, with its disruption of international trade, investment and travel, according to Hwang. It crystallised into the “domestic-international dual circulation” strategy announced in May 2020, she said.

“The dual circulation strategy called for giving domestic ‘circulation’, or domestic supply and demand, the centre stage in economic development while keeping enough openness to the international market to maintain supply chains.”