Nairobi tollway an example of China’s new belt and road financing approach in Africa

- The expressway opening in Kenya’s capital is part of a shift by China’s Belt and Road Initiative away from debt financing towards public-private partnerships

- Chinese lenders have become more cautious in financing infrastructure projects on the continent, concerned about borrowers’ ability to repay loans

A CRBC subsidiary, Moja Expressway, will operate the road for 27 years to recoup the investment through toll fees.

In all, the road marks a gradual shift in the belt and road strategy, from public debt finance to a new method of funding for infrastructure like roads and power plants in Africa: public-private partnerships (PPP).

Under the PPP model, Chinese private companies can lower the risks to repayment and help African governments reduce their loans and budget deficits, observers say.

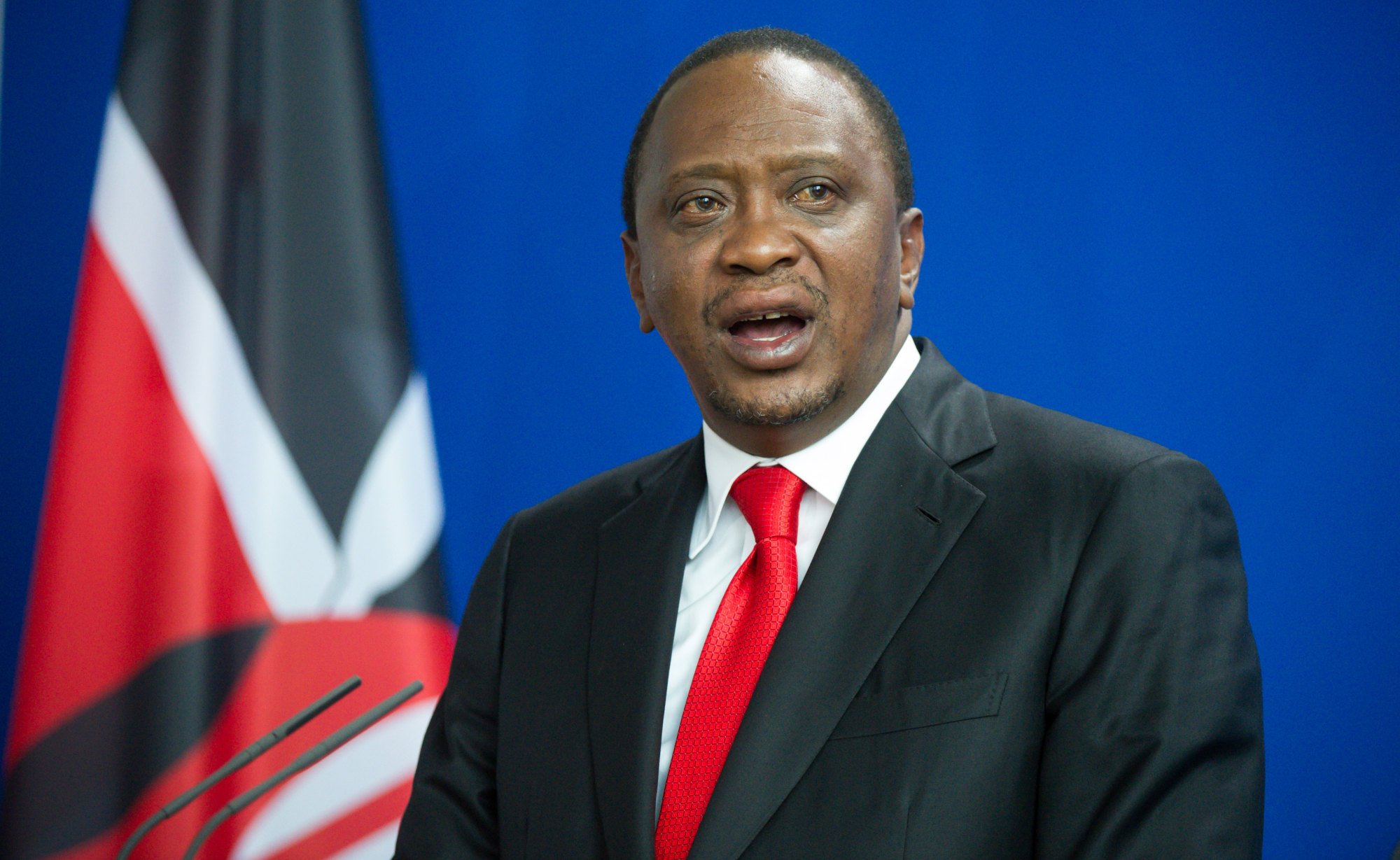

The Nairobi Expressway opened to public use on a trial basis on Saturday, ahead of an official launch next month. The tollway is expected to ease traffic flows in and out of Nairobi’s city centre by reducing traffic congestion on Mombasa Road, which runs alongside it. The deal to build the expressway was struck in September 2018 during the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing, when Kenyatta met Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Models suggest that CRBC will bring in US$20 million from tolls during the road’s first year of operation, with revenues expected to rise to more than US$100 million a year by 2043.

Sovereign loans for African infrastructure have in many parts of the continent become economically too risky and politically costly

This comes as Chinese lenders have become more cautious in financing infrastructure projects, with the country’s policy banks growing increasingly concerned about borrowers’ ability to repay and are thus warier about extending finance.

In 2018, China’s Export-Import Bank refused to finance an extension of Kenya’s Standard Gauge Railway.

Chinese officials say the new caution does not mean Beijing is cutting funding for African nations, but just that it will use more creative ways to finance such projects.

Xi plays up roles for private sector in China-Africa trade and finance

During the FOCAC meeting in Senegal in November, a statement from Chinese officials said “China would continue to offer grants, interest-free loans, concessional loans and other financial support to African countries”.

“Innovative ways of financing will be explored” to support Africa’s infrastructure development, the statement added.

Discussing the expressway last year, Wu Peng, once the Chinese ambassador to Kenya and now the director general of the foreign ministry’s department of African affairs, called it “a stellar example of a Chinese-invested infrastructure project that supports development of Africa, and a boon for motorists.

“We’ll continue to promote such projects.”

Increasingly, Beijing has incentivised its state-owned companies as well as private Chinese firms to enter into PPPs abroad.

Xi has pledged to undertake 10 African “connectivity assistance” projects, all to be partly financed through joint ventures and PPPs.

Chinese infrastructure financing in Africa has in recent years undergone a gradual shift from sovereign loan funding to project finance PPPs, according to Tim Zajontz, a research fellow at the Centre for International and Comparative Politics at Stellenbosch University in South Africa.

“Sovereign loans for African infrastructure have in many parts of the continent become economically too risky and politically costly, as a result of mounting controversies around issues of debt sustainability,” Zajontz said.

Are Chinese belt and road debt burdens larger than previously understood?

He said Chinese construction firms had mobilised significant capacities onto African markets over the past two decades. As sovereign debt-financed funding for infrastructure dried up, Chinese firms had had to adapt their accumulation strategies, Zajontz said.

“After all, Chinese firms – just like companies from elsewhere – are not operating on a charitable basis but are profit-seeking enterprises, irrespective whether they are state-owned or not,” he said.

To keep up demand for Chinese firms in overseas markets, Beijing has begun to promote PPPs with Chinese firms as a “win-win” solution in times of debt distress.

Tollways in the Global South were lucrative investments for foreign firms, Zajontz said, especially because they were usually backed by sovereign guarantees and minimum-revenue provisions, which ensured profitability.

But those projects can come with challenges. Zajontz said public-private partnerships, like the arrangement for the Nairobi Expressway, privatised public goods – often affecting those populations with the smallest disposable incomes disproportionately.

China paints picture of African partnership with gleaming public works

W. Gyude Moore, a former Liberian public works minister, said that in the last decade – especially after the introduction of the belt and road plan – many African states reached the limits of how much debt they could responsibly take on.

At the 2015 and 2018 FOCAC meetings, China pledged US$60 billion over each three-year period, Moore, now a senior policy fellow with the Centre for Global Development, noted.

“One way that African governments have attempted to get around these constraints and still build their infrastructure has been through PPPs,” Moore said, adding that autonomous and quasi-autonomous state-owned enterprises – such as utility companies or road authorities – had entered into PPPs.

“For both the Chinese side and their African partners, this seems mutually beneficial. In theory it should help improve project selection and governance since both lender and borrower need to ensure repayment,” Moore said.

He said African states, however, needed to tweak the process to allow third-party validation and scrutiny of the costs of these projects, since many would still carry implicit government guarantees, with the financial risks that entailed.